I am in turmoil. In April 19 letter to The Ethicist in the New York Times, a woman wrote that her “boyfriend said that he would save their cat rather than a stranger if both were drowning”. She asked the ethicist, “Is this morally wrong?”

In my view, the ethicist – Kwame Anthony Appiah – responded correctly. He noted that people who have pets experience:

a duty of care toward their animal companion; the creature depends on them and, over time, they’ve developed a strong bond: a sense of affection, companionship, loyalty, all twined around a whole lot of memories. So the choice of plumping for your pet is, you could say, very human.

Nontheless, he wrote, “

But yes, it’s very wrong…Those human strangers? They had rich emotional lives and they had plans, short-term and long-term, big and small; it’s a good guess that they were also part of other people’s plans, other people’s emotional lives. They had friends, co-workers, kin, dependents — maybe some assortment of parents, children, siblings, cousins — and possibly a spouse or life companion. You can expect the suffering that their death will bring to be deep, the ripple effects wide.

I finished reading the article secure in my sense that the ethicist had communicated the right judgment, and that it would be convincing.

But then I read the comments that readers provided. I was shocked by the number of people who said that they would choose to save an animal over a human being.

I did quick analysis of the data. I classified each response into one of three categories: the commentator unambiguously chose the pet, the human stranger; or made some other response (rejected the question; said that they would save both; commented on something other than the question at hand, etc.). I found that 38% of the commentator chose their pets; 21% chose the stranger, and 37% commented on something other than the question.

Of course, this is not a representative sample; this is a sample of people who chose to read and respond to this particular article on ethics in the New York Times. But still – 38% of respondents said that they would choose the cat.

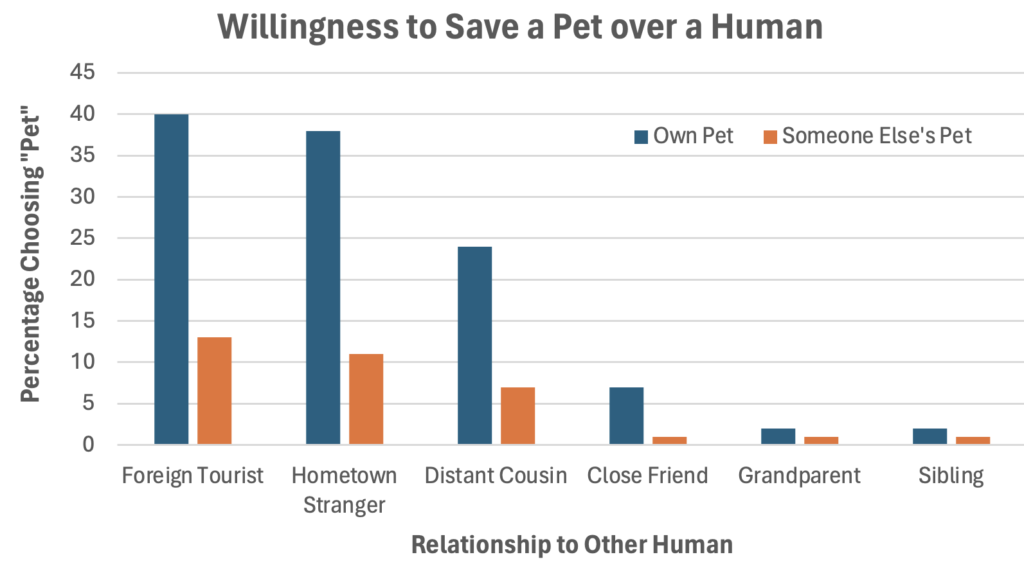

This is consistent with a research study (Topolski et al., 2013) that the ethicist cited. In this study, researchers asked people to choose whether they would save a pet or another human from drowning. However, they varied the relationship that respondents had to the human in question. What if the human were a perfect stranger? A stranger from your hometown? A distant cousin? A close friend, grandparent or sibling? They also varied whether the pet in question was one’s own or another person’s. The results are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Willingness to Save a Pet versus a Human (Adapted from Topolski, et al., 2013).

The results are very illuminating. Given a choice between one’s own pet and a stranger, a sizable minority of respondents — 40% — indicated that they would choose their pet. However, as their relationship with the other human become closer, people were increasingly less likely to choose the cat over the human. The same effect happens when people choose between “another person’s pet” and humans with whom they have increasingly close relationships. However, people are much less likely to choose the pet if it is someone else’s pet than if it were their own.

Why Would People Choose their Pets over Human Beings?

Why might people say that they would choose to save their pets over a human stranger? People love their pets. Many who do so regard them as part of their families. They treat their pets as if they were their own human children. Pets are experienced as part of a person’s “in group” – their kin. While pets are part of “us”, human strangers are “them”. They are members of “out-groups”. As a result, we have no obligation to them.

A perusal of the comments from the New York Times article suggests that this is indeed the case. In defending their choice to save their pets, respondents gave many types of responses. First, many commentators justified their decision to save their pets in terms of their love for their pets. Such people said that they had close, loving relationships with their pets and would not be able to part with them:

I know and love my cat, and I would be devastated if she drowned. I can’t say the same for a stranger, even if their life is objectively richer/more valuable than my cat’s…

Animals who live in our household are family members. They enrich our lives with love, loyalty and companionship. They never betray us or abandon us.

Some people love their pet more than any person in their lives. To them such a choice would be unfair and agony.

Others said that they had obligations toward their pets that were more important than those they had toward strangers. They often invoked the idea that pets are more vulnerable than other humans.

After all, I’m a grown adult who as about 5,000 times more agency, power, and control over the world, than my dog does. I am capable of taking care of myself. Our dog is totally helpless and dependent on us. We all love each other, but our pup NEEDS us.

Household pets are vulnerable and completely dependent on us. They are also full blown family members. My choice would be to save my pets just as I would save my children. To me, this is unconditional love.

Sorry, honey. I love you to the moon and back. I meant every word of our vows. But Fluffy is my child.

Some suggested that there was no reason to value human life over the lives of other animals.

To survive on earth, humans need to learn that we are not inherently more important than any other species. Believing that we are superior and entititled is blatant human exceptionalism, or—to put it more bluntly—human supremacy.

Everything he says about the value of a human life…Further, there is a bond between a human and a pet. applies equally well to animals.

Human life is not more valuable than animal life, and we do not know the rich internal lives that animals may have.

Why This is Troubling

The desire to put a loved pet before an unknown stranger is a very human response. Nonetheless, I must admit: I find such views very disturbing. It is not that I do not understand the sentiments of those who say that they would choose their pets over a stranger. On the contrary, I find them disturbing because such sentiments are all too understandable. If I were to experience my dog as my close kin – even as my child — why wouldn’t I want to save my dog over a stranger?

And herein lies the rub.

This troubles me because it demonstrates what I believe is perhaps the most central problem that we face when it comes to relating to each other, namely, the difficulty we have in seeing the humanity of people who are unfamiliar to us. I do not scorn people who experience their pets as human kin. Instead, I lament the fact that, at least under certain circumstances, it is easier to see “humanity” in a cat than in another human. As Appiah says, we turn our loved animals into “fictive kin”. That our kinship with our pets is “fictive” does not render our relationships with them any less real.

However, this phenomenon illustrates a basic fact that we must seek to overcome. The mere fact that we are all part of the human family is insufficient for us to see each other as human. Instead, our capacity to see the humanity in others relies upon our relationships with them. It is our inability to feel an embodied relationship with others that breeds dehumanization during times of conflict. Dehumanization leads to intractable social and political polarization.

Don’t believe me? Some who commented on the New York Times piece stated that, in comparison to their cats, some people’s lives weren’t worth saving. Consider the following:

Maybe if the person was Albert Einstein or someone of real value to the world, I’d reach for them first.

[I] think it is absolutely unethical to save the cat first. That said, if it were this guy’s cat or Donald Trump, Matt Gaetz, Marjorie Taylor-Green, Lindsey Graham, or a host of other vile MAGA buffoons, I’m saving kitty and feeling good about my unethical choice.

No Republican’s [Democrat’s] health is worth more than my snowball’s.

While it may be possible to comprehend the sentiments behind these statements, they are nonetheless repugnant. One need not agree with a Trump, Gaetz, Taylor-Green, or Graham — or a Biden, Obama, Clinton or Sanders for that matter – to understand the repugnance of locating the value of their lives below that of a cat – however loved the animal might be.

It is an obvious truth that we cannot be in relationships with all people in the world. If we are able to treat our pets as “fictive kins”, we should be able to find ways to treat our human kins with some degree of “fictive kinship” as well.

Reference

Topolski, R., Weaver, J. N., Martin, Z., & McCoy, J. (2013). Choosing between the emotional dog and the rational pal: A moral dilemma with a tail. Anthrozoös, 26(2), 253–263. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.2752/175303713X13636846944321

If you like what we are doing, please support us in any way that you can.