To end political polarization, we have to care about the needs, problems and grievances of our opponents. We have to care about their values. And we may even have to care about them.

Sound crazy? That’s part of the problem.

Donald Trump has now been elected to be President of the United States for a second time. About half of the nation is rejoicing. About half of the nation is in despair.

The election was billed as the most important one in our lifetime. Many have suggested that Donald Trump is an authoritarian figure who has demonstrated his hostility to democratic values. Exit polls showed that the most important issue for Harris supporters was the state of our democracy. (For Trump supporters, it was the economy).

Would the election of Harris have saved democracy? Will Trump’s election save democracy? No — neither a Trump nor a Harris Presidency would or will save democracy. That is because the threat to democracy does not lie in either party – despite what you might think of whoever is on “the other side”.

We live in an adversarial democracy. an adversarial democracy seeks to resolve political conflict through peaceful debate between opposing parties. Instead of making collective decisions through fiat, force or physical violence, debates pit two people or parties against each other in a competition for votes. Because different parties disagree on the issues of the day, for adversarial democracy to work, opposing parties must agree on a more-or-less shared common set of democratic norms and values. They must agree, for example, on the general type of nation that they want to promote. They must agree on the rules for how democratic decision making is intended to work. Without such a “shared common ground”, a democracy risks fragmentation. A nation can easily splinter into opposing groups who are unable to solve their political conflicts.

We are close to living in such a nation. At various earlier periods in American history, citizens tended to share a common conception of what they wanted the nation to be. They disagreed primarily on preferred ways of achieving more-or-less shared goals. In contemporary times, we are rapidly losing the “shared common ground” that unites diverse political parties. We are losing faith in the beliefs that enable opposing parties engage in democratic politics.

Beyond such differences such in vision, partisans have begun to lose faith in traditional beliefs about how democracy should operate. This is shown on the political right in the form of resistance to the transfer of power, acceptance of the attempt to overturn the 2020 Presidential election, and the broader attempt at insurrection. On the left, some would suggest it has taken the form of advocating limits on free speech, elevating group rights over individual rights, and the promulgation of what has been called “cancel culture”. Partisans on both sides are willing to misrepresent each other in a desire to achieve power. Both sides seem unable or unwilling to seek political compromise.

If we want to “save democracy”, we are going to have to stop thinking that victory for one party over the other is going to do it. If we want to save democracy, we have several choices. We can

The first option relies upon some degree of faith that our problems are somehow going to fix themselves. Perhaps. But that’s not likely.

The second option has promise. However, while our adversarial system has kept us intact for several centuries, it is important not to romanticize it. It has not always worked smoothly. There are many times when our adversarial politics have threatened to tear the nation apart. These include but are not limited to the Jefferson-Adams election; the civil war, the Great Depression, the McCarthy era, the 1960’s, the murder of George Floyd, and other significant events.

It is possible that our adversarial democracy, while not perfect, is the best that we can do. It can work, but we’ll just have to live with the imperfections. Alternatively, it is also possible that democracy is still evolving. It’s possible that we can do better.

In our current way of thinking, the moment a discussion turns political, people become signaled to take sides. They debate. Their goals are not to solve problems, but instead to win. They move against each other. Winning brings triumph, losing results in humiliation. There is thus much at stake for the individuals involved.

There is a third option:

We can try to supplement or even replace our adversarial system with more collaborative forms of democracy.

Democracy is government of the people. There is nothing in the concept of democracy that says that democracy must be adversarial. A more collaborative approach to democracy can occur when we apply principles of conflict resolution to the problem or resolving political opposition. Instead of thinking of politics as a battle between opposing forces, political decision-making becomes a form of collaborative problem solving – where the problems to be solved are meeting the unmet human needs of each party to a political conflict.

This requires a shift in perspective. It requires that we try to see the other not as an opponent who we must defeat, but instead as a fellow human being whose behavior is an attempt to meet some unmet human need. We must begin to see that beneath the other’s political position is a human need, interest, desire or plea. When we do this, we can often see that the other’s need – the deep problem that they are trying to solve – is not incompatible with our own. The moment that we realize this, the other ceases to be our enemy. We can begin to realize that it is possible for seemingly opposing parties to work together to solve each other’s problems at the same time.

Instead of me against you, it can be me and you against the problems we are both trying to solve. At this point, debate over political positions can be transformed to a kind of collaborative problem solving.

Still sound crazy?

Quite often, the deep problems that our opponents are trying to solve are not incompatible with our own. They may even be the same as our own! The moment we see this, it becomes easier to care about the other party’s needs. It is possible to care about meeting the other person’s needs even if we disagree vehemently with their ideological positions.

The key to doing this is to separate – at least at least temporarily – the other party as a person (or group of persons) with problems and needs from their ideologies and political positions.

A party’s political position is a way of solving a problem or meeting a need. A person’s political position is typically a way of solving any given problem. There are, of course many ways of solving any given problem. If we work to actively care about the problem our opponent is trying to solve, we can join forces with them to create ways of solving both of our problems at the same time.

It is possible to care about your opponent. Caring about your opponent and their problem does not mean giving in to the other. It does not mean sacrificing one’s own needs.

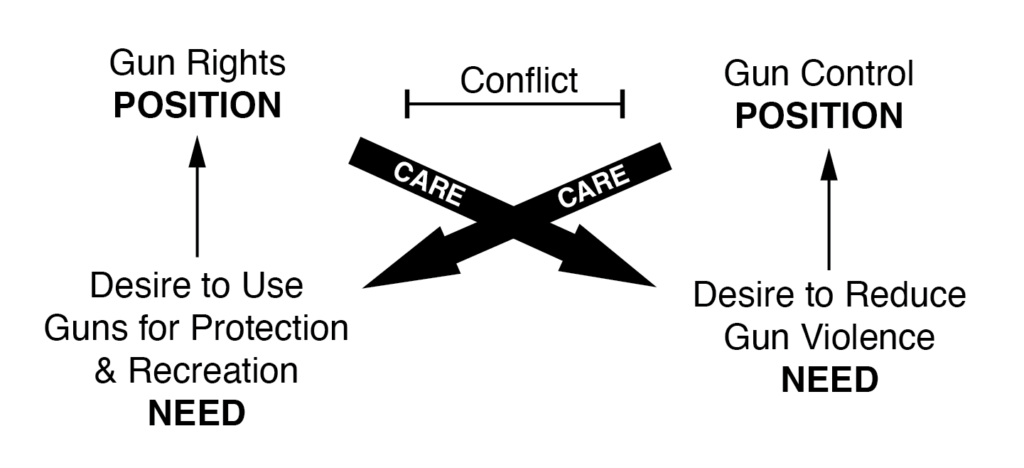

To understand how it is possible to care about the problems of your opponent, it is important to understand the distinction between the political positions that people take and underlying human needs that truly motivate people. A political position is the “side” that a person or party takes on an issue. A position is a kind of pre-emptive solution to a problem that has not always been named. For example, Figure 1 shows two basic positions that can be taken on the issue of gun rights. Some people take the position that citizens should have the right to own guns; others believe that some form of government control over guns is possible.

People can provide a suite of reasons to justify their political positions. These reasons, however, are not important to the present discussion. Indeed, when people try to justify their positions in a debate, they tend to exacerbate the conflict. They do more to entrench the conflict than resolve it. (When was the last time you changed your mind in a debate about a political issue?) People do not often change their positions in a debate – no matter how compelling the reasons provided by the other side. It’s hard to care about the positions of someone who is trying to oppose you.

Figure 1. Caring about the Needs that Motivate Different Positions on Gun Ownership

To cultivate care for the other, it is necessary to understand that a person’s political position is largely (but not exclusively) an attempt to solve a problem or meet an unmet need. The need is different from the position! The position is a kind of way of solving a problem or meeting a need.

What happens when we seek to understand the human needs that motivate each side’s position? What motivates someone to advocate a pro-gun position? What are their needs? They may have a need or desire to use guns for purposes of protection and for recreational purposes. What motivates someone to advocate a gun control position? Such individuals may have a need to reduce gun violence.

In a collaborative approach, resolving political conflict is a matter of finding novel ways to simultaneously meet the needs of each party to a conflict. While this needs to be discussed further, this is not my concern at this point. My concern is how to we prompt one party to care about the concerns of the other party – to care about the needs and problems of the party who they regard as their opponent.

The answer I want to suggest is illustrated in Figure 1. Partisans will disagree with the political positions of their opponents. However, if we look beyond the ideology (at least for now) to the underlying need, it is difficult not to care about the other’s problems and pleas.

How many advocates of gun rights would not care about the desire to reduce gun deaths? How many advocates of gun control could not understand the desire to protect oneself and one’s family? Can the gun control advocate not understand – and perhaps even care – about the desire to use guns recreationally? Even if a gun control advocate dislikes, say, the act of hunting, can they not at least understand why some would enjoy or desire the freedom to hunt?

To identify the needs of the other is to connect with the soft underbelly of the reasons why they take a given positilon. We can now feel compassion for the other. We can now care about what they want, even if we do not agree with their preferred way to obtain what they want (their position).

Once we understand and care about the needs, concerns and grievances of the other, we don’t need to focus on political positions anymore. Instead, we can try to find innovative ways to meet each other’s needs.

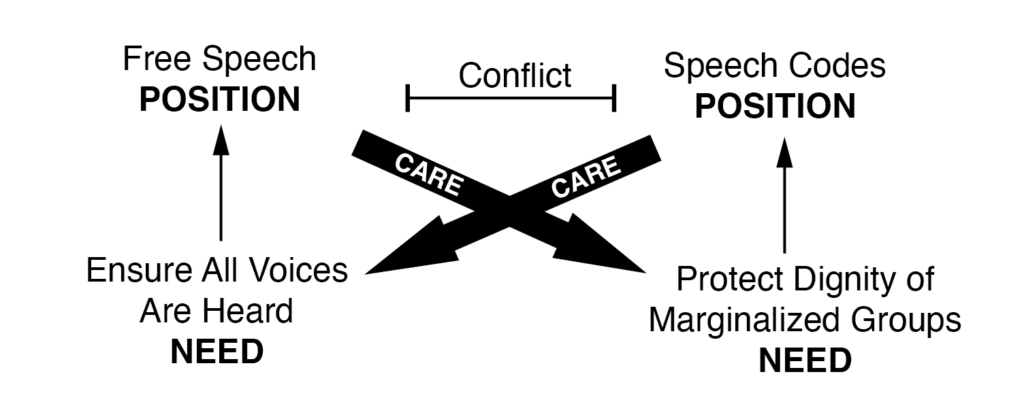

There are as many examples how to care about the needs of one’s opponent as there are issues about which people disagree. Consider the issue of free speech versus speech codes. People differ on the question of how to manage speech that can be seen as hurtful to others or to social groups. In any given discussion of contentious issues, some adopt the position that free speech is essential; others suggest that some forms of speech – speech that can be seen as racist, sexist, classist, ableist, and so forth – should be prohibited.

Figure 2. Caring about the Needs that Motivate Different Positions on Free Speech

Although people disagree vigorously on this issue, they are less likely to disagree with the human needs that motivate people to advocate these positions. One might suggest that people who advocate free speech have a need to ensure that all voices are heard on an issue. They may have a need for honesty in expression, or a desire to ensure that unpopular positions are not squelched so that they can be addressed directly. People who advocate speech codes have a need to protect the dignity and feelings of traditionally marginalized groups. It is unlikely that people on either side of the free speech issue would not have some degree of compassion for the needs that motivate those positions. Again, a resolution of the conflict between people on this issue can be resolved by ignoring initial political positions and seeking novel ways to meet the underlying needs of each party at the same time.

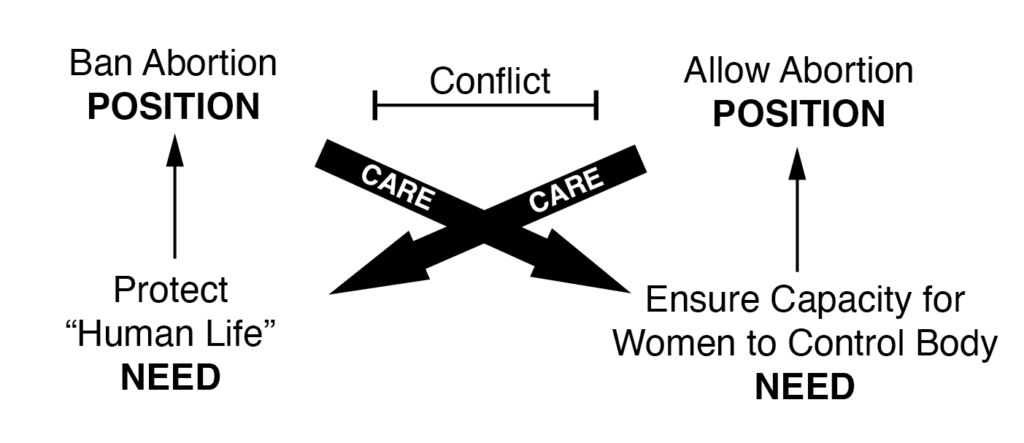

A final example involves the difficult issue of abortion. People who take different positions on the issue of abortion often demonize those on the other side. What are the needs, interests and feelings of those who take different positions on this issue. Many people who advocate anti-abortion position have a genuine belief that the fetus – even at early stages of development – is a person, a “human life”, or at least a human organism at an early phase of development. People who hold this belief have a genuine need to protect what they regard as a human life. Alternatively, because pregnancy comes with significant physical and emotional risk to women, people who are pro-choice are often motivated by a desire to ensure that women have the capacity to make decisions about their bodies.

Figure 3. Caring about the Needs that Motivate Different Positions on Abortion

As is the case in each of the examples discussed, regardless of one’s political position on the issue of abortion, if actively attend to the genuine needs and concerns that motivate political positions on both sides, it is difficult not to have care and compassion for those concerns. It may be true that a person who adopts a pro-choice position may not agree that an early developing fetus is a person or a human life that is deserving of protection. However, such a person should be able to appreciate the dilemma of a person who has such a belief. Conversely, it may be true that someone who advocates a pro-life might put greater priority to the life the developing fetus than to the woman’s desire to control her body, but they should be able to appreciate and care about the concerns of women to do not feel this way.

If the choice on question of abortion is either pro- or against, there is no way out. However, if we look beneath the opposing positions, we find needs that are at least understandable. To make a dent in political polarization, we must work to care about the problems that our opponents are trying to solve.

We are not merely individual beings; we are relational beings. We exist in relation to each other. When we interact, we learn from each other. When we look beyond the surface positions, we experience the other’s humanity, we can act out of care for them. Acting out of care does not mean giving in on our core needs. It does mean being open to finding new ways – ways that no one has yet thought of – to meet simultaneously meet our different needs. When we do so, we not only solve the problem at hand, but we can each become transformed by the experience.

If you like what we are doing, please support us in any way that you can.