We live in a polarized and fragmented world. Our democratic traditions are threatened by tribalism and intergroup conflict. Politics and the media foster division and moral outrage. We can and must do better. Creating Common Ground (CCG) helps people learn to bridge divides on interpersonal, social, and political problems. We do this in several ways:

We live in a polarized and fragmented world. Our democratic traditions are threatened by tribalism and intergroup conflict. Politics and the media foster division and moral outrage. We can and must do better. Creating Common Ground (CCG) helps people learn to bridge divides on interpersonal, social, and political problems. We do this in several ways:

The Center for Collaborative Democracy

Thinkers, Scholars and Doers

Instruction and Workshops

Consulting and Outreach

CCG Magazine

The CCG Community

The Center for Collaborative Democracy is a group of scholars and practitioners who are seeking alternatives to our current forms of adversarial democracy. We conduct research, consult with organizations, and provide online instruction to help people bridge interpersonal, social, and political divides.

CCG Magazine is an online magazine in which scholars, practitioners, and intelligent people like you propose novel ways to bridge divides on contentious social and political issues. Bridging divides isn't easy. It takes creativity, courage, and a desire to embrace complexity. Might you be a CCG contributor?

The CCG Community meets monthly for talks, workshops, and discussions designed to cultivate new ways of relating to each other in our personal, public and political lives. Among its goals, the CCG community seeks to bring an ethos of collaborative problem-solving forward to effect change in our personal, organizational and political spheres of influence.

Michael F. Mascolo is Professor of Psychology at Merrimack College in North Andover, Massachusetts. He is the Academic Director of the Compass Program at Merrimack College, an intensive, year-long academic and socio-emotional immersion program for first-year college students. Dr. Mascolo received his Ph.D. at the University at Albany — SUNY and performed postdoctoral work at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. He is the author and/or editor of six books. These include From Conflict to Collaboration: A Step-by-Step Guide to Solving Problems in Everyday Relationships (2021, Absolute Author); The Handbook of Integrative Developmental Science (2020, edited with Thomas Bidell, Routledge/Taylor & Francis), 8 Keys to Old School Parenting for Modern Families (2015, Norton), Psychotherapy as a Developmental Process (2010, with Michael Basseches, Routledge/Taylor & Francis, Culture and Developing Selves (2004, edited with Jin Li, Jossey-Bass), and What Develops in Emotional Development? (1998, edited with Sharon Griffin, Plenum). He is also the author of over 100 articles, book chapters, and reviews on topics related to human development. He is also a life coach on issues related to conflict management, parenting, teaching, and personal development.

We live in a polarized and fragmented world. Modern society is facing what might be called a crisis of meaning – the loss of a shared sense of what is good, meaningful and worthwhile in our lives. Examples of this crisis are ubiquitous. Our shared democratic traditions are being threatened by tribalism, polarization, and intergroup conflict. Politics and the media foster division and moral outrage. In the absence of a shared sense of social values, people retreat into their own private systems of belief. However, they ultimately find themselves cut off from each other, and longing for a sense of community where they can create the types of relationships and connections that make life meningful and worth living. In the absence of genuine connection, people find themselves soulless, alienated, and empty. This is seen in the mental health crisis where rates of addiction, depression, anxiety, suicide, and nihilism are rising at alarming rates.

We need a new ethos for living in the 21st century.

This is not something that we can do alone. We must collaborate to find new, shared ways of being together — new values that bring together and even transcend different and conflicting ways of being in the world.

A relational ethos is one that builds upon but goes beyond the concern for the isolated individual. A relational morality is one that acknowledges that we are both individual and relational beings. As individual beings, we recognize that each of us is different: I am not you, and you are not me. However, as relational beings, we embrace the idea that we become persons only through other persons. We develop who we are through our relationships with others.

A relational ethos embraces at least three core moral values: rights, virtue, and care for others.

Western society has traditionally been concerned with the rights of individuals. This is as it should be. However, a singular focus on rights alone distorts the human condition. Our rights do not exist without responsibilities. Any individual right is always balanced by a set of responsibilities that we have to others. Our right to free speech brings with it the responsibility to listen to and respect the speech of others. It comes with a responsibility to ensure that our speech does not produce actions that harm. Even if we acknowledge the inseparability of rights and responsibilities, an ethical system based on rights alone is insufficient.

Virtue refers to moral goodness. When we act out of virtue, we attempt to bring our behavior into correspondence with conceptions of the good. To be concerned with virtue is to care about character — about the type of person I want to be, the kind of business or organization I want to lead or be a part of, or the moral identity of who we are as a nation. To act out of virtue is to seek to be and do good. Of course, what constitutes goodness is necessarily something that is always open to discussion. We cannot determine what is good in the absence of deep engagement with each other.

When we invoke an ethos of care, we act out of concern for others. Care requires the cultivation of emotions such as compassion, empathy, sympathy, and love for the other. Acting out of care does not mean sacrificing the self for the other; it means giving of ourselves to the other. When we foster the well-being of others, our selves become enhanced. We experience our own vitality — the power that comes from being alive and being a part of something larger than ourselves.

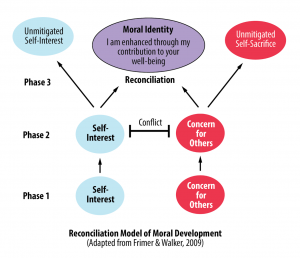

The theologian John MacMurray said that humans are guided by two dominant motives: fear for the self and love for the other. In virtually every interaction with have with others, we always seek to navigate between these two poles. A relational ethos builds upon both poles of this human tension. It acknowledges them and seeks to bring them together in ways that resolve their tension. Within a relational conception of persons, moral selves arise when we learn to reconcile self-interest with concern for others (Frimer & Walker, 2009). We can think of our moral identities as developing in three broad steps.

The first step begins at birth. Even in infancy, children show both self-interest and concern for others. Their self-interest is easy enough to observe. Infants cry when they are hungry, resist having objects taken away from them, and so forth. While it may be harder to see concern for others in infants and young children, it’s nonetheless there. Newborn babies cry more loudly when they hear the cries of other babies – an early form of empathy. By 8-months, some children begin to spontaneously help other people in need (they might pick up something that was dropped).

At this point in development, however, self-interest and concern for others tend to develop separately. In some situations, they act out of self-interest; in others, they show concern for others. But these two motives are separate – a child typically shows one or the other, but not both.

Although self-interest and concern for others tend to develop separately during early childhood. However, over time, children begin to experience conflicts between self-interest and their concern for others. For example, a child may want to keep a toy, but realize that her friend is sad without one. In such situations, self-interest conflicts with concern for others. At this level of development, children become aware of the conflict but have difficulty resolving it. For example, they may go back and forth between wanting to keep a toy for themselves and sharing it with someone else.

As children enter into adolescence, their sense of self changes dramatically. They begin to ask questions about the type of person they want to become. Part of this process involves asking questions about how to resolve conflicts that arise between self-interest and concern for others. Over time, as adolescents and adults construct their identities, they have several choices. They can:

1. Ignore the needs of others and build identities organized primarily around self-interest;

2. Ignore self-interest and build identities organized primarily around concern for others;

3. Reconcile self-interest and concern for others into a seamless moral identity.

It is this last choice that brings about a moral identity – a sense of self that is neither self-interested nor self-sacrificing. To reconcile self-interest and concern for others is to identify oneself with caring for others. It is to make the concerns and interests of the other part of one’s own identity and sense of who one is. When this happens, it is possible acting out of love for others is experienced as something that enhances rather than diminishes the self. Caring for others is not something that is selfless, but instead is something that enhances the self.

If you like what we are doing, please support us in any way that you can.