To Solve Difficult Problems, Think Beyond Opposites: The Case of Higher Education

Institutes of higher education throughout the U.S. are facing substantial challenges for both finances and values. Challenges in terms of academic liberty, free speech, respect for diversity coincide with financial struggles that threaten not only the quality of education but also the very survival of many universities.

Many of these institutions are in the process of engaging its faculty, staff and students in a series of conversations on values and practices of inclusion, diversity, human rights and social justice. Faculty, staff, and students recognize and express both concerns and aspirations regarding such core values in the context of ongoing practices. This process can be represented by a system of values (institutional values and practices). At the same time, universities face substantial financial challenges, which exert significant pressures on many levels of functioning as an academic community. These challenges require an examination of current and projected fiscal realities, which in some universities are highly dependent on enrollment. This process can be characterized by a system of finances.

These two systems respectively represent intrinsic values and material concerns. We are simultaneously facing challenging realities and issues regarding these two relatively opposite systems. This experience reflects a paradox. Financial priorities appear very different from the humanistic educational aims that represent intrinsic values. Mission-based aspirations for inclusion, diversity and social justice appear isolated from financial constraints that reflect material necessities.

On the other hand, (a) these two systems are related, and (b) the complexity of the present challenges calls for comprehensive, inclusive, and deliberative approaches rather than reductionist and compartmentalized attempts. There is a need for approaches that recognize and facilitate both the differentiation and the integration of the system of values and the system of finances. It is in this developmental context that a process-relational perspective can be useful.

Reconciling Oppositions

When we are faced with opposing commitments, beliefs, or values, we often feel stuck. If two things are in opposition, how can they be reconciled? Can two opposing thoughts be true at the same time? Can two conflicting values be honored simultaneously?

More often than we might think, the answer can be “yes”. To understand why, it is helpful to go back to some of the world’s great thinkers. We can start with Hegel (1807/1977) and his famous popularization of dialectical thinking. According to Hegel’s philosophy, conflict between two systems involves a tension between opposite poles: a thesis leads and relates to its opposite, namely, an antithesis. When a thesis and its opposite come together, they create a conflict. Although we often feel that tension between opposites cannot be resolved, this is not the case. From Hegel’s perspective, a developmental solution to a conflict can often be found in the vertical creation of a new system that includes but transcends the systems in conflict. Through the coordination of the two conflicting systems, a new, comprehensive and more inclusive system emerges as the synthesis. The synthesis is a higher-order way of thinking. It brings together both a thesis and its antithesis into a single system while simultaneously resolving the contradiction between them.

Using Dialectical Thinking to Solve Problems in Higher Education

The problem of the relation between finances and values can be characterized in a variety of ways. First, it is a problem of isolation. Issues associated with the educational values and those that represent the need for stable finances have often been addressed in isolation from each other. Second, the problem can also be seen in terms of the competition or tension between two systems. For example, in response to significant challenges, we often tend to adopt either a financial or value-based approach. In so doing, we may attempt to defend one system against the other. This tendency may be related to feelings, perceptions, and beliefs of viewing the two systems as antinomies that are in competition.

Financial problems may seem to jeopardize or weaken the pursuit of aspirational values, which may further be compromised by financially based attempts for solutions. Likewise, there may be fears that decisions based on aspirational values may ignore and worsen financial challenges. Widespread difficulties about inclusion, diversity and justice may even intensify financial problems.

This tension may be one of the reasons why financial problems and educational issues tend to be treated in isolation. However, recognizing this tension and the possible connections between these two systems can create new, integrative, and sustainable solutions. How can the system of institutional values reconcile with the system of financial realities?

There are, of course, two extreme alternatives. One can adopt a highly materialistic orientation that is inattentive to aspirational values, or a rigidly idealistic approach that ignores financial realities. Each extreme represents resistance against taking into account the necessities of the other side. The constructive step, however, is to move away from extremes toward a novel, more inclusive resolution to the problem. To work toward a resolution to the problem, we can recognize three moments of analysis that lead to an eventual synthesis.

Overton (2015) proposed a three-step process in the developmental analysis of elements and systems in conflict. In this three-step developmental process, the first moment involves developing an awareness of the interdependence of opposites (or what Overton called the “identity of opposites”). This involves seeing the ways in which opposites – even as opposites – rely on each other and operate as a single unit. The second moments involves forming an understanding of the distinctiveness of opposites (what Overton called “opposites of identity”) — that is, to understand the separate, distinct and unique identity of each opposite. The third moment is the developmental synthesis of a new whole (what Overton calls “synthesis of wholes”) – that is, the creation of a new way of thinking that includes but nonetheless transcends and resolves the contradiction between the opposites in question. In what follows, I illustrate each of these moments in the context of a discussion of the clash been values and finances in the higher education.

The Interdependence of Opposites

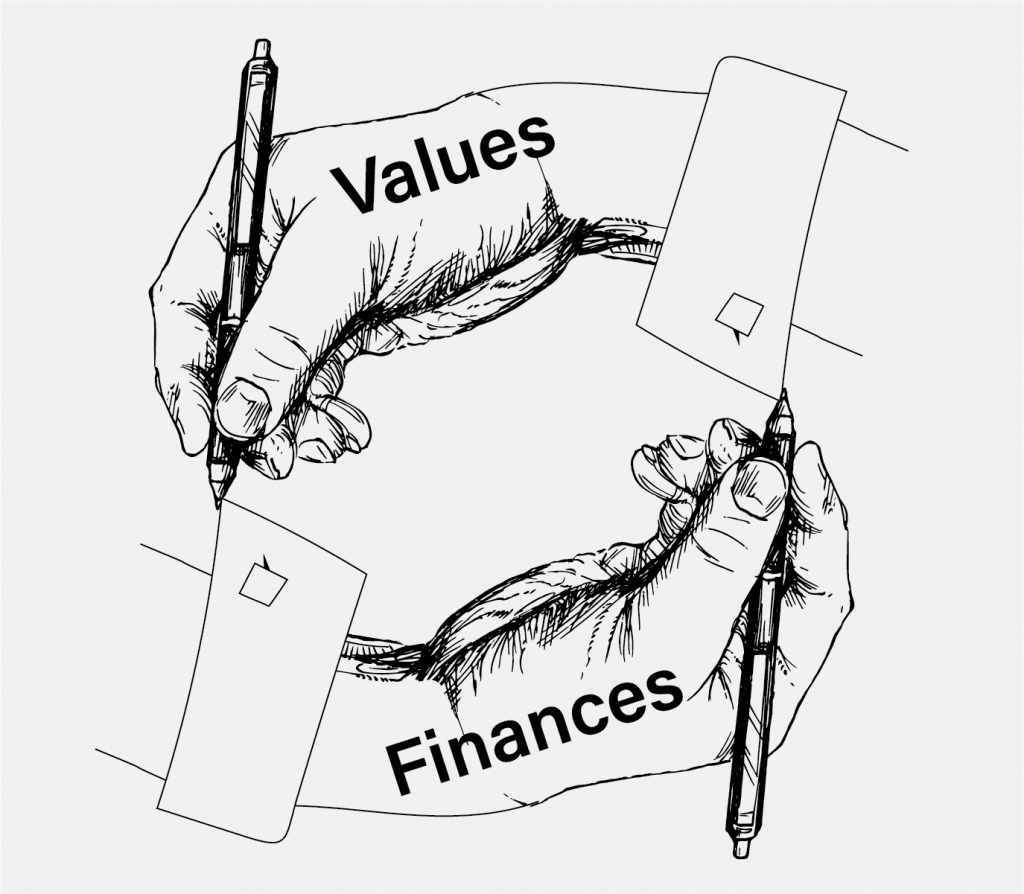

The first step involves a recognition that the system of values is intertwined with the system of finances. The fact that a problem (e.g., decline in enrollment) is financial in no way denies that it is about our values. The fact that a problem is about our values in no way denies that it is financial. The problem is 100% financial and 100% about institutional values. In the operation of a higher education institution, the system of finances does contain and in fact is the system of values; the system of values does contain and is the system of finances (see Overton, 2015, p. 41).

The system of values both constitutes and is constituted by the system of finances. The mutually constituting relation between values and finances is represented in Figure 1 as an Escher-like painting of hands drawing hands:

Figure 1. Hands Drawing Hands

(Adapted from Escher, 1951)

Articulating Opposing Identities

In the second moment, the two systems are temporarily differentiated from each other to produce a more detailed examination of their distinct properties. Thus, in this phase of analysis, instead of focusing on the ways in which the two hands “make each other up”, we now focus on the two different hands themselves. There are financial factors and considerations that can be seen as distinct from value-based issues and questions. This moment of analysis creates “relatively stable platforms” for inquiry. These platforms consist of different standpoints, points-of-view, orientations, or storylines; they operate as different perspectives in a multi-perspective world.

Formulating specific questions from the standpoint of the different perspectives involved in an issue can help illuminate what is at stake when viewed from each pole of the conflict in question. We can ask: what are our values as an academic community? How are these values operating in practice? What are the major psychological and institutional challenges in the realization of our aspirational values? Which values and practices violate the aspirational values? Are there implicit and powerful institutional values, beliefs, practices, and commitments (i.e., hidden curriculum) that are competing with and undermining our aspirational values? What assumptions and arguments are typically invoked to justify or legitimate these values in practice?

Alternatively, we can ask, what are the major financial issues? What are the possible short-term and long-term changes that could reduce costs and increase revenue in the operation of each department? What are the enrollment trends that represent financial problems? What are the various ways that we have of creating new income?

Synthesizing New Wholes

The third moment represents a synthesis of new wholes (what Overton calls “synthesis of wholes”) that actively coordinates the two conflicting systems. What is a system that is broad and inclusive enough to be able to integrate the two systems? In the present application, this is likely to be a system that reflects an essential commitment for members of a university. This way, the community, with its two conflicting systems, can be united by a process of growth that the new synthesis represents.

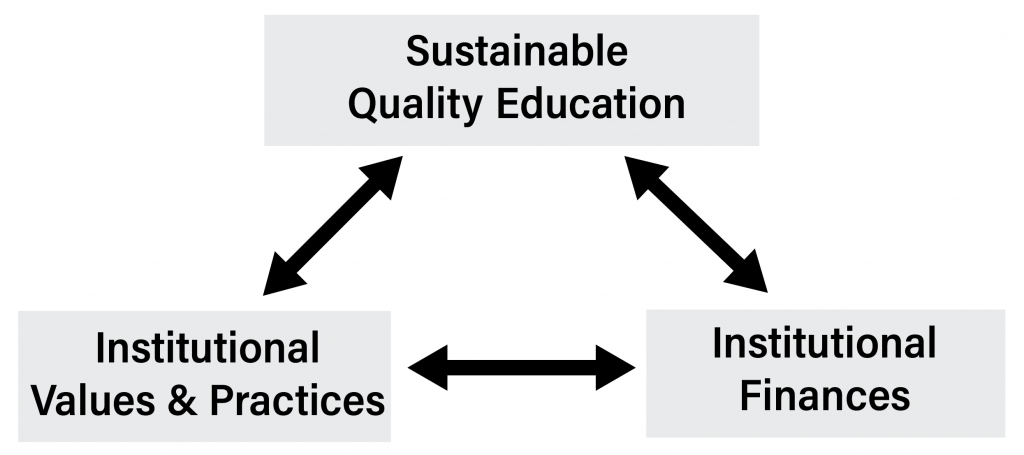

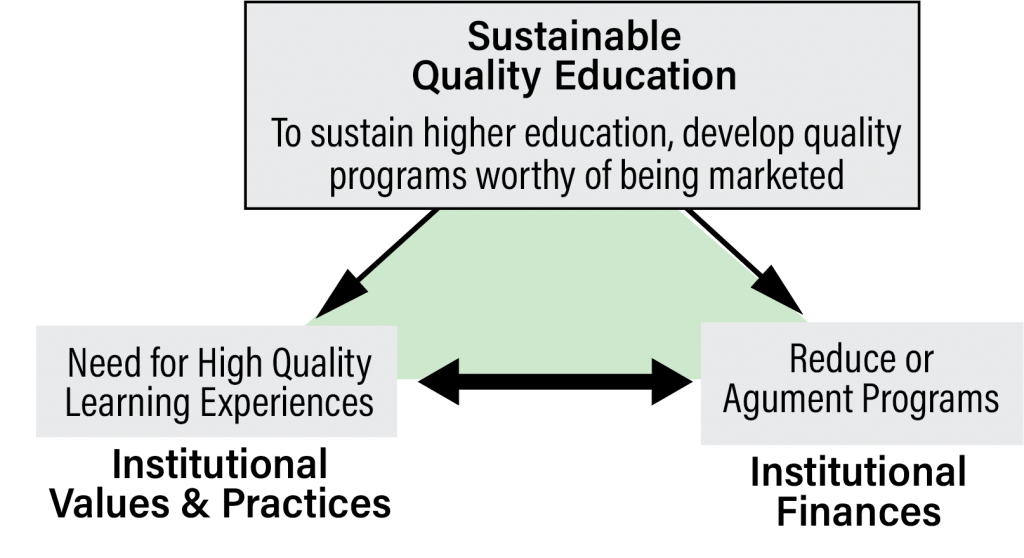

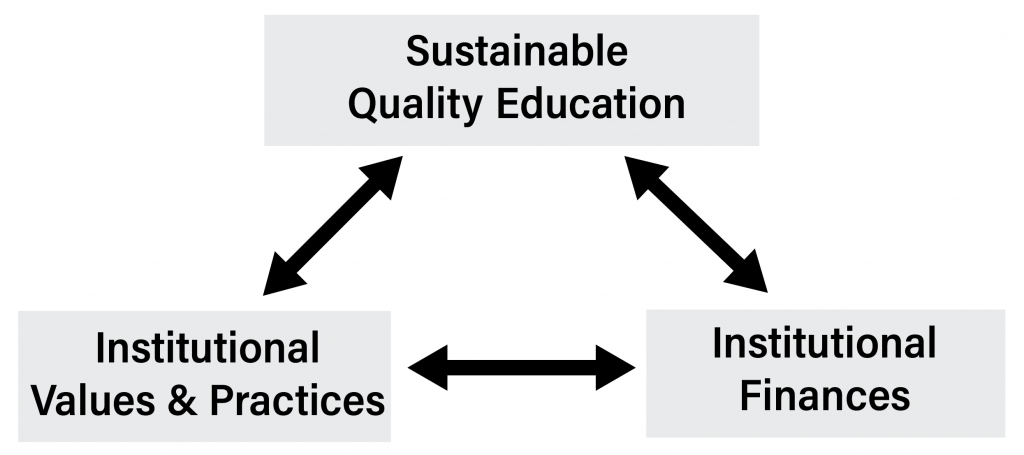

Figure 2. Synthesizing a Novel Whole

Sustainable quality education is a candidate for the new system of synthesis, integrating the system of values and the system of finances. This represents high quality education based on a sustainable financial and psychosocial foundation in an increasingly complex world. The psychosocial aspect of the new system includes values, beliefs, attitudes, behaviors and practices that constitute a community. From this perspective, integrative, inclusive, and holistic solutions can be found, without reducing the evaluation (the problem or the solution) to a single dimension such as marketability or material gain.

How New Wholes Create New Questions from New Points of View

At the level of the synthesis, three new standpoints emerge. Rather than focusing on a single, absolute, exclusive, and fixed criteria for evaluation, the three standpoints provide three relative points of view on the problem. Specific solutions to the problem emerge through the coordination of multiple standpoints. The coordination of multiple points of inquiry lead to better, more inclusive, and more stable solutions to any given problem.

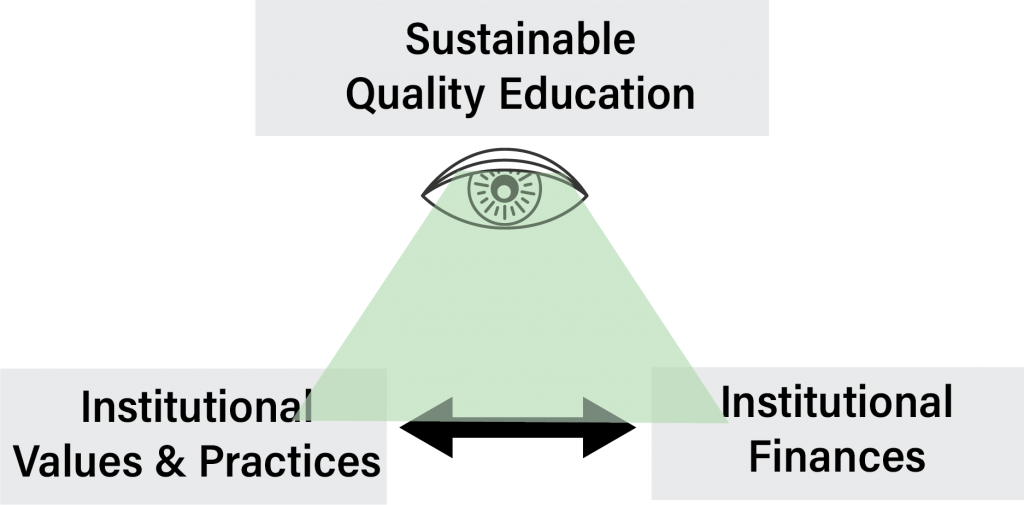

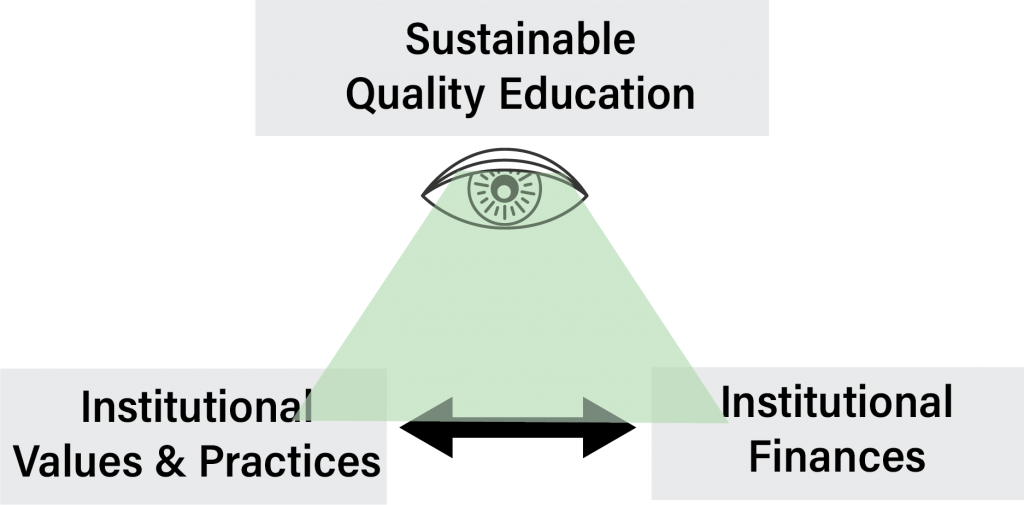

The first set of questions occurs as we look at the problem from the standpoint of Sustainable Quality Education. That is, from the standpoint of promoting Sustainable Quality Education, how can we coordinate Institutional Values and Institutional Finances?

Figure 3: The Standpoint of Sustainable Quality Education

When seeking to coordinate Values and Finances as viewed from the standpoint of Sustainable Quality Education, one might ask:

1.1. What are the goals of sustainable quality education in the context of our aspirational values?

1.2. How can these goals about high quality sustainable education be fulfilled, considering current financial challenges?

1.3. Which specific aspects of high-quality sustainable education can directly serve and strengthen both our aspirational values (e.g., increase self-awareness, improve recognition of social justice and diversity) and financial status (e.g., increase revenue and reduce costs)?

1.4. What problems exist regarding quality of education, and how are these problems related to our values and finances?

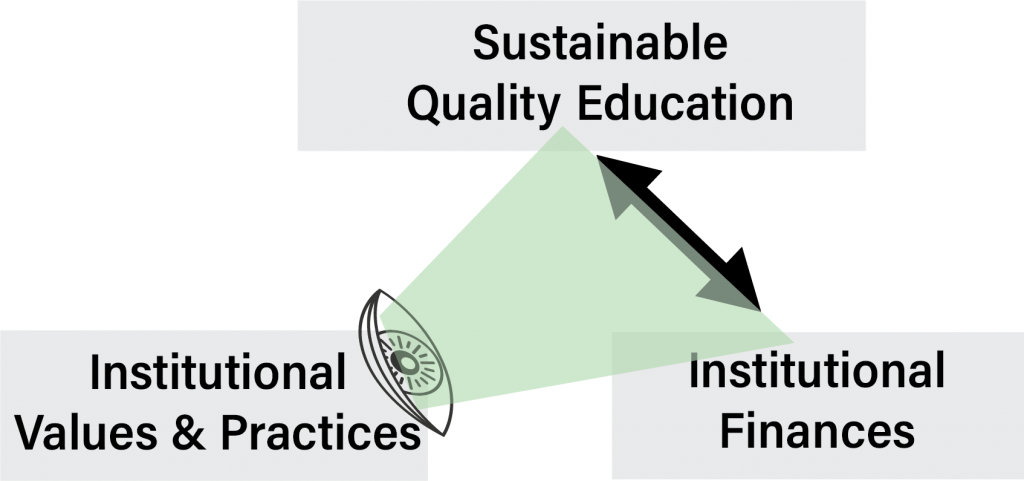

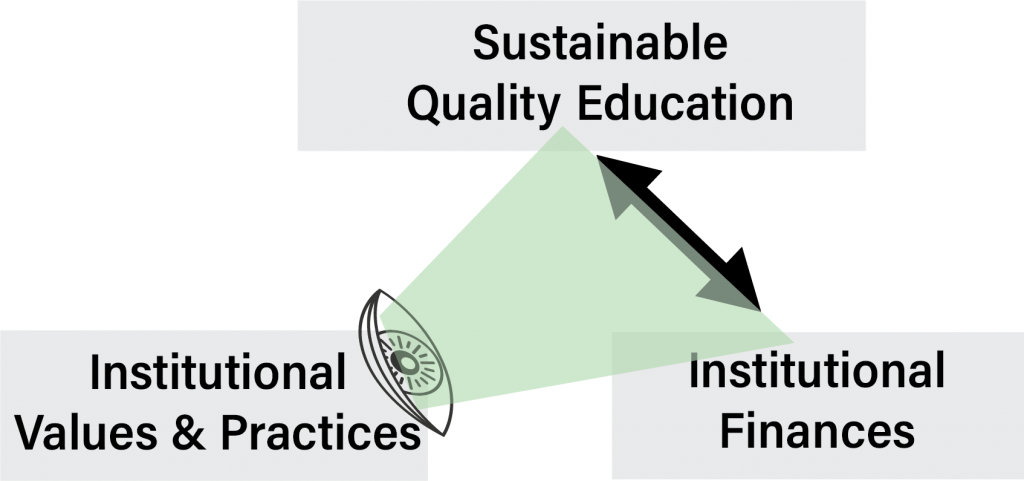

A second set of questions occurs as we look at the problem from standpoint of Institutional Values and Practices. That is, from the standpoint of seeking to promote Institutional Values and Practices, how can we coordinate Sustainable Quality Education and Institutional Finances?

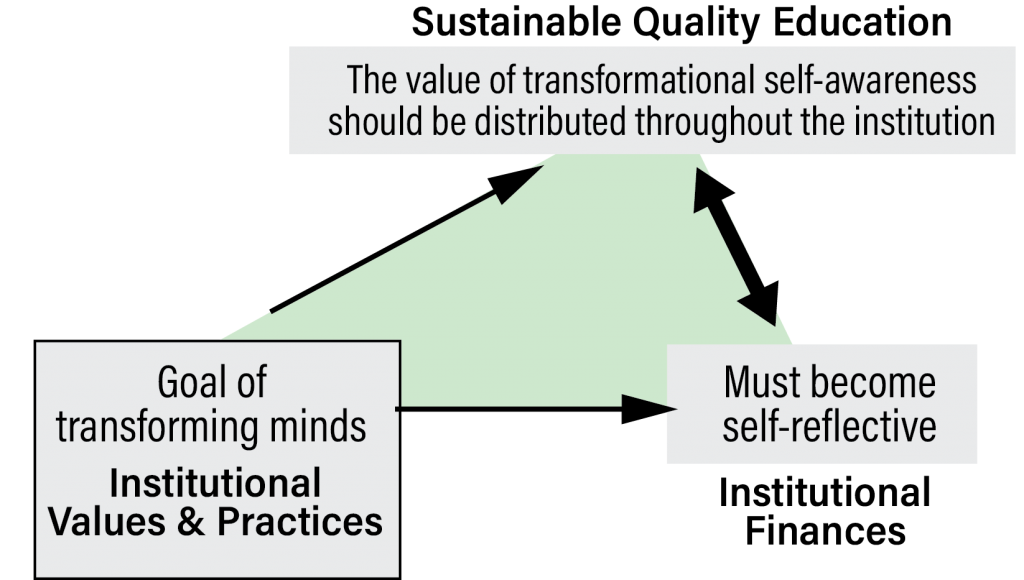

Figure 4: The View from Institutional Values

When seeking to coordinate Sustainable Quality Education and Institutional Finances as viewed from the standpoint of Institutional Values and Practices, one might ask:

2.1. What are our major problems regarding diversity and inclusion, and how could these problems be manifesting as issues in enrollment and finances?

2.2. Which specific institutional values and practices are reflected by current financial problems?

2.3. What are the major existing and aspirational, implicit, and explicit values and practices of our institutional culture in the context of sustainable quality education?

2.4. How can the aspirational values be effectively protected, supported and put into practice, considering existing financial pressures?

2.5. The exercise and realization of which specific values can both improve high quality sustainable education and strengthen the institution financially?

2.6. Which values and practices negatively affect both high quality sustainable education and the financial vitality of the institution?

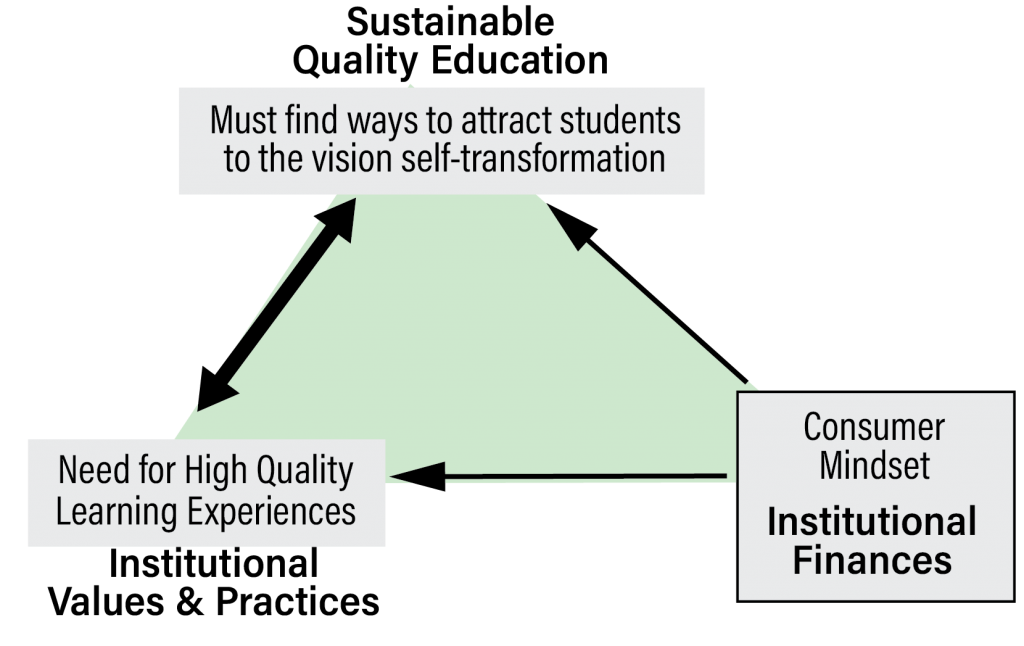

The third set of questions occurs as we look at the problem from standpoint of Institutional Finances. That is, from the standpoint of seeking to sustain Institutional Finances, how can we coordinate Sustainable Quality Education and Institutional Values?

Figure 5: The View from Institutional Finances

When seeking to coordinate Sustainable Quality Education and Institutional Values from the perspective of Institutional Finances, one might ask:

3.1. What are the current financial problems and goals in the context of sustainable quality education?

3.2. How can these problems be solved, and goals reached, considering our aspirational values?

3.3. Which institutional practices about budget and finances reduce the realization of our aspirational values (e.g., make collaboration and inclusion more difficult and reinforce isolation and competition between individuals and departments)?

3.4. Which specific financial practices can both increase the quality of education and support our aspirational values?

3.5. How do financial problems negatively affect the quality and sustainability of education, undermine our aspirational values, and reinforce undesirable values and practices.

Problem-Solving within Emergent Standpoints

Thus far, the dialectical method has brought us to the point where it is possible to see the non-independence of the problems that confront any given institution at any given time. When we identify the various forms of opposition that arise in any given institution, it is possible to see that they are defined in relation to each other. As a result, any particular problem must be solved with reference to the other problems within the system that make up the institution. The parts of a system must be understood in relation to each other, and in relation to the overall functioning of the system as a whole. This is the essence of systemic thinking.

In what follows, I consider the ways in which problem solving can be approached holistically from the variety of standpoints that emerge from the juxtapositions of opposites. Drawing on these different standpoints, in the context of higher education, I provide an initial sense of how opposites can be coordinated in an attempt to solve systemic problems of an institution.

The View from the Whole: The Need for Integrative Mission

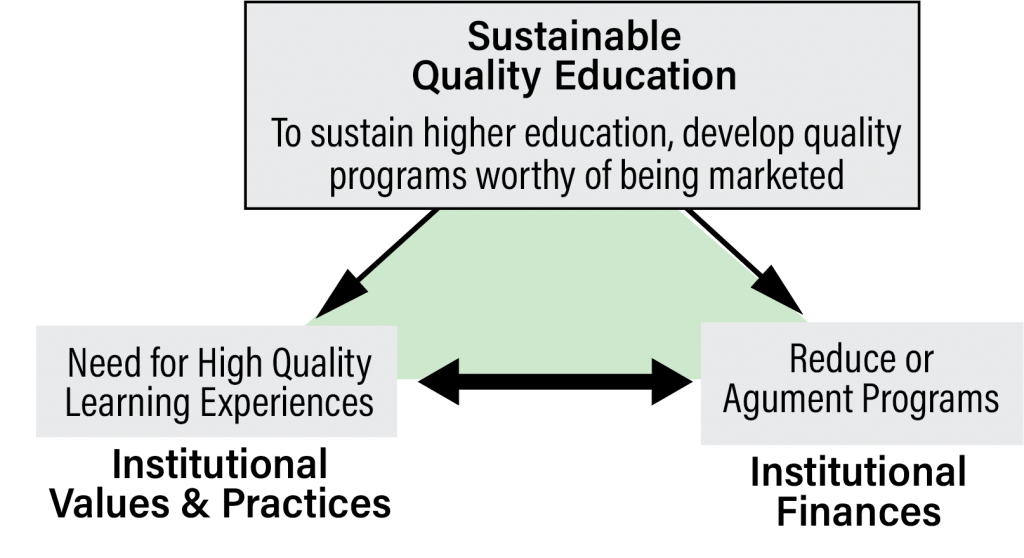

Let us begin by examining the need to understand the opposition between institutional values and financial problems in higher education. In so doing, we can examine how problem solving can occur when values and finances are viewed from the standpoint of overarching institutional principles. Considering the possibility that financial problems reflect issues about values, it is important to recognize and identify various ways in which these two systems are intertwined. This is indicated in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Synthesizing Values and Finances in terms of Broader Institutional Principles

Imagine that a group of people were seeking to find ways to resolve fiscal challenges within the context of institutional values. One group might approach the problem by advocating for simplifying program offerings in order to attract a broader range of students, while another might encourage complexifying the range of programs in order to achieve national notoriety. Both solutions focus primarily on managing financial matters in the absence of a reflective understanding of institutional values. Heller and colleagues (2017) warned against national trends to simplify the meaning and value of education:

We believe that we must resist that simplification, that our future as a viable institution depends on our courage to do so. It is our challenge, we maintain, not to create programs that are marketable, but to create programs that are deserving of being marketed.

Any sustainable solutions to the problem of maintaining high quality education in times of financial constraint is best founded on a new synthesis between institutional values and sustainable finances. From this point of view, a college or university might seek to formulate programs on the basis of “the unending and ever-changing quest for engaged learning on a foundation of ecological, civic, creative, humanistic thinking . . . rather than in the pseudo-corporate language of entrepreneurship” (Heller et al., 2017).

Figure 6 illustrates how the relation between values and finances can begin to be reconciled in terms of overarching institutional principles. The key is to directly confront the opposition between assumptions about fiscal constraint and institutional values. How can high-quality education be offered in the context of fiscal constraint? An initial answer comes from the synthesis of a higher-order principle that incorporates both concerns into a single whole: To sustain quality higher education, it is necessary to create quality programs that are marketable to new generations of students.

The View from Finances: Addressing the Consumer Mindset

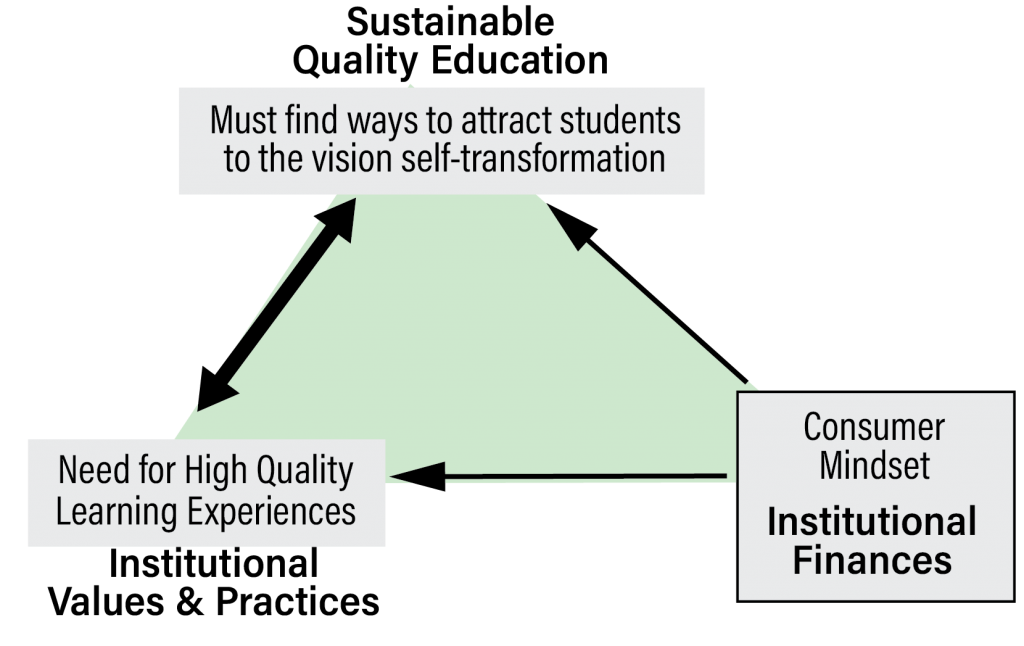

Having articulated an overarching principle, it becomes helpful to adopt the perspective of other elements in the institutional triad. Let us consider the view from the standpoint of seeking stable finances. One of the ways in which finances influence high quality education is through the operation of the consumer mindset within educational institutions. Consumer mindset reflects a primarily business mentality. This approach is particularly relevant in institutions that are financially dependent on enrollment. According to this mentality, students are customers and educators are customer service representatives that aim to please.

As shown in Figure 7, this approach must be differentiated from the institutional values and goals of support, caring, empathy and compassion. These significant goals are more likely to be realized from a progressive perspective, when the aim of education is development (Kohlberg & Mayer, 1972), as John Dewey originally proposed. More specifically, the aim of education can be the transformation of minds through a combination of challenge and support based on an understanding of each person’s unique life history and possible developmental pathways.

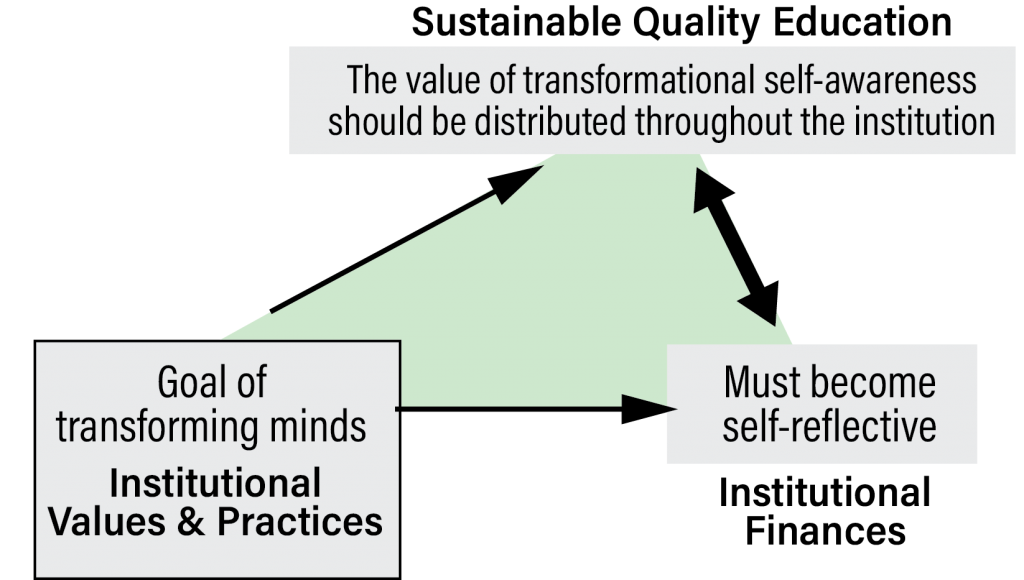

Figure 7. Transforming Financial Ideology on the Basis Institutional Principles and Values

The financial mindset that the student is a consumer who must be approached from the standpoint of providing customer services is significantly different from the aim fostering the development and transformation in students. Actualizing the latter goal often involves effort and direction that students – understood as customers who are purchasing a commodity – may be unwilling to accept. As such, the operation of the consumer mentality must be understood in the context of its actual impact on both academic standards and values – as well as values such as fairness, justice and equality. As an implicit belief, some might make the judgment that a consumer mindset is necessary to assure the financial viability of a university in today’s world. Nonetheless, this belief must be recognized, questioned and examined.

Far from representing and strengthening care and concern for the actual well-being and complex problems of students in today’s world, the consumer mentality masquerades as care and concern. This moral masquerade (Batson, 2008) intensifies existing problems of both values and finances, rather than reducing or solving them. In Hegel’s (1820/1952) terms, this is a show of care, rather than its essence. This mindset feeds the coddling of the American mind (Lukianoff & Haidt, 2018) rather than empowering students toward increased awareness, well-being and resilience.

The operation of the consumer mindset must be recognized in various contexts of everyday functioning in an educational institution. Is it really serving financial sustainability? How is it impacting diversity, equity, inclusion, justice, and a sense of community? How does it relate to, and possibly contrast with, our actual responsibilities toward students in their learning and development? How is this mindset influencing the quality of education at a university? The operation of this mentality may be a significant barrier against the true integration of the systems of finances and values. It is possible that the consumer mentality jeopardizes not only academic integrity and fairness, but also the financial sustainability of the local institution, or even of higher education as a whole. As such, it may be necessary to transform the consumer mindset ideology to accommodate opposing values and institutional principles.

The View from Values: Realizing Mission Across Constituencies

In June 2018, a group of Lesley University faculty, staff and administrators discussed issues of human rights, diversity and justice as part of the Cultural Literacy Curriculum Institute. One of the recommendations that emerged at this institute was an institutional commitment to learning as a continuous process that facilitates self-awareness. Ongoing educational programs for faculty, staff, administrators and students can be coordinated and improved in order to facilitate the process by which faculty, staff, administrators and students can recognize their own biases. Such an increase in self-awareness can be seen as an aspect of transformative learning, which was described as follows:

Transformative learning involves experiencing a deep, structural shift in the basic premises of thought, feelings, and actions. It is a shift of consciousness that dramatically and permanently alters our way of being in the world. Such a shift involves our understanding of ourselves and our self-locations; our relationships with other humans and the natural world; our understanding of relations of power in interlocking structures of class, race and gender; our body-awarenesses, our visions of alternative approaches to living; and our sense of possibilities for social justice and peace and personal joy (Morrell & O’Connor, 2002, p. xvii).

Figure 8 illustrates contributions to institutional problem-solving that arise when elements of the problem are viewed from the standpoint of institutional values. Given the value of fostering transformational learning through the development of self-awareness, one might ask, does the university have the resources to create an institutional culture that actively supports community members toward increasing self-awareness? What steps can be taken to fulfill this potential, and turn such aspirations into sustainable action? An institutional commitment to promote self-awareness can be a useful step in this direction of identifying and creating the mechanisms for this support system. When this commitment is made salient, and repeatedly emphasized across the schools and programs of the university, values of diversity, inclusion, justice and belonging are more likely to be reflected in day-to-day operations throughout the university.

Figure 8. Distributing Values and Mission Across the Institution

For example, every department meeting can be seen as an opportunity for further realization of this vision. Such an engaging process of “departmental learning” can strengthen an essential aspect of accountability in everyday practice. This reflects enhanced integration of mission with daily operations. Such an integration is likely to reduce fragmentation and isolation, and increase the vitality and the wholeness of overall institutional functioning.

To the extent that an institution is founded on self-awareness (or some other value), then, as shown in Figure 8, this same self-awareness – a quality assumed to be cultivated in students and teachers – is something that can and must also inform financial assumptions and analyses. Thus, the analysis of financial gain must move beyond considerations of mere fiscal restraint and incorporate, as part of its strategy, the mission, self-awareness and the way in which this new conception of the institution is understood by community. One must not think of financial considerations as in competition with considerations of value – and certainly not as in competition with the beliefs that constitute the larger whole (to provide a sustainable quality education). If there is tension among values, the tension itself must at least be recognized if not addressed and resolved. The alternative – suppressing the tension or taking one side over the other – would foster regressive rather than progressive change in the evolution of the institution.

Various initiatives and programs that focus on community can be systematically coordinated as integral parts of the university’s renewed and vital mission for continuous learning that promotes self-awareness. As a result, meetings and workshops about values such as diversity and inclusion can have significant educational value that is not limited to catharsis or free self-expression. Rather, such meetings and workshops can become important steps in a continuous process of individual and collective self-discovery and transformation in which all members of the university participate. Moreover, participation in such programs can become a significant aspect of the performance evaluation process for staff, faculty and administrators.

Fostering Systems Thinking in Higher Education and Beyond

One of the implications of thinking of institutions as dynamic processes rather than fixed things is that crises can be opportunities for transformation. By recognizing and examining the tension between the system of values and the system of finances, each of these systems can be better understood in terms of both their actual operation and possibilities of growth. Considering and understanding them as co-equal, complementary systems will enable their coordination. Through this coordination, a new system of high-quality sustainable education is likely to emerge as a new synthesis. This system both organizes and is organized by the systems of values and finances.

High quality sustainable education needs an inclusive system of values to be integrated with an efficient system of finances. In this integration, the meaning of each system “completes itself in the other” (Hegel, 1807/1977, p. 474), giving rise to and sustaining high quality education. The new system will in turn sustain and support both the distinctive qualities and the integration of institutional values and finances. If this transformation is achieved, a new and truly inclusive institutional consciousness can emerge, representing high quality sustainable education. Then the current problems that many universities are facing regarding values and finances can be remembered as the “birth-pang of its emergence” (Hegel, 1807/1977, pp. 456-457).

Becoming an inclusive community that is truly committed to truth and justice is a highly valuable goal in and of itself. However, for universities that are founded on progressive ideals, such a goal is not optional. For many institutions of higher education, the realization of an inclusive community is a vital requirement, as a foundation for both financial viability and educational quality. The new synthesis emerges from this requirement.

————————————-

References

Batson, C. D. (2008). Moral masquerades: Experimental exploration of the nature of moral motivation. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 7, 51-66.

Hegel, G. W. F. (1952). Hegel’s philosophy of right (S. W. Dyde, Trans.). Clarendon Press.(Original work published 1820)

Hegel, G. W. F. (1977). Hegel’s phenomenology of spirit. (A. V. Miller, Trans.). Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1807)

Heller, C., McKenna, M., Naso, P., Rauchwerk, S., & Weber, N. (2017, November 10). Comments from GSOE faculty members. Lesley University, Cambridge, MA.

Kohlberg, L., & Mayer, R. (1972). Development as the aim of education. Harvard Educational Review, 42(4), 449-496.

Lukianoff, G. & Haidt, J. (2018). The coddling of the American mind: How good intentions and

bad ideas are setting up a generation for failure. Penguin.

McDonald, J. P., & the Cities and Schools Research Group. (2014). American school reform:

What works, what fails, and why. The University of Chicago Press.

Morrell, A., & O’Connor, M. A. (2002). Introduction. In E. V. O’Sullivan, A. Morrell, & M. A. O’Connor (Eds.), Expanding the boundaries of transformative learning: Essays on theory and praxis (pp. xv-xx). Palgrave.

Overton, W. F. (2015). Processes, relations, and relational-developmental-systems. In R. M.

Lerner (Series Ed.), W. F. Overton & P. C. M. Molenaar (Vol. Eds.). Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Vol. 1. Theory and method (7th ed., pp. 9-62). Wiley.