The dangers of retreating into our own private morality.

“Liberty cannot be established without morality” — Alexis de Tocqueville

Over the past half century or more, modern individualism has run up against a contradiction[1]. The United States was founded upon principles of freedom and individual rights. Our right to make choices free from government intrusion makes it possible for citizens to pursue lives based on their own conceptions of what is right and good. In this way, our individual rights make a genuinely moral life possible. Beyond this affordance, however, our rights have little to say about how we should live our lives. Our capacity to live good lives requires voluntary investment in social and moral values that extend beyond our foundational rights[2]. Over the course of the American project, however, our commitment to shared community values has declined[3]. As a result, instead of seeking our identities in systems of social and moral virtue, we tend to retreat into our own private moralities[4]. However, as moral concerns necessarily bring us outside of ourselves, there can be no truly private morality.

The “freedom to be me” has become so deeply engrained in the American psyche that it has become difficult to acknowledge its effects. Challenging this precept would seem to undermine the very core of the American sense of self. Nonetheless, it underlies a broad range of ills. We have become an increasingly polarized nation, separated by difference, certain of our rectitude, sensitive to offense – all without a means for bridging the increasingly expansive gaps that divide us.

If we are to evolve past this contradiction, we will have to find new ways to understand our relationship to difference. We cannot always celebrate differences, as not all differences are benign. We cannot always tolerate difference, as not all differences are endurable. We cannot resort to violence; as violence begets more violence. Instead, we must develop ways to coordinate self-interest with the interests of the other — even under conditions of deep disagreement. We to shift our moral ethos from one organized primarily around the right to self-determination to one that also includes a commitment to public virtue, moral character and care for the other.

Moral issues involve concerns about what ought to be. Across time and place, moral issues have spanned a broad range of principles, including liberty/oppression; rights/injustice; virtue/vice; care/harm; hierarchy/equality; loyalty/betrayal; purity/pollution; sanctity/profanity; harmony/conflict,[5] and others. While different cultures tend to emphasize different moral concepts, the full range of moral concerns can be found in virtually any cultural group. Given the breadth of moral thinking across time and place, philosopher Charles Taylor defines the concept of morality broadly as judgments that involve strong evaluation[6] – that is, judgments of right and wrong, good and bad, and worthy and unworthy.

Moral considerations extend beyond liberty, justice, and rights. The founders of the American experiment understood this. In fact, it was largely because of this understanding that they created a political system based on negative liberty. Negative liberties grant citizens freedom from external intrusion on their everyday affairs. The separation of church and state was intended to support and foster the open and voluntary proliferation of moral and religious thinking among the population.

During the early and middle phases of American history, personal freedoms were held in check by a public morality informed by religion, shared virtues, and communitarian values. In 1776, Adam Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations, which is often taken to be the foundational philosophy of free market capitalism. One might expect Smith to have been an advocate of unmitigated self-interest. However, this was far from the case. Smith also authored The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which outlines a moral structure for an individualist society. Smith’s version of moral individualism embraced three cardinal virtues. Prudence guides the practical pursuit of self-interest. Justice secures individual freedom from state interference. Beneficence — the highest human motive in Smith’s thinking – reflects the voluntary desire to bestow good upon others.

For Smith, virtue, “fellow-feeling”, responsibility and duty were moral foundations of personhood; they were understood as ideals to which individuals should voluntarily aspire. For Smith, living up to standards of virtue brings social approval; failure yields disapprobation. Through such sanctions, parents teach children to internalize and act on shared moral standards. Over time, children gain the power of “self-command” and the corresponding capacities for conscience, self-approbation and self-disapprobation. As a result, a person gains a self by identifying with a system of social values. I am not simply a set of personal goals and desires, I am my virtues, values and character.

Thus, in earlier periods, the American moral ethos included but was not restricted to a rights/justice orientation. It was accompanied by what psychologists call virtue/character and care/community moral orientations. These orientations were defined in terms of systems of shared and contested values that people were expected to live by. The virtue/character orientation raises questions about the types of persons that we should become. A person of character is one who identifies herself with some system of shared moral virtues (e.g., honesty, hard work, compassion, etc.) and seeks to act in accordance with them[7]. In the care/community orientation, actions are judged with respect to the principle care; a moral act is a caring one that is performed out of concern for the interests, needs and welfare of the other[8].

Shifts in the American Moral Ethos

The American moral ethos has shifted considerably over 240 years. In that time, our sense of rights, equality and autonomy has strengthened, while our commitment to virtue and care have waned. Psychologist Jonathan Haidt has called this the “Great Narrowing” of moral frameworks[9]. The ascension of individual rights was a slow and hard-won journey. For half American history, the issue of rights was driven primarily by the problem of slavery. Over time, individual rights were gradually extended to slaves; the suffrage movement slowly brought the vote to women. As the ethos of rights grew, so did the emphasis on self-determination. Parental values shifted from an early emphasis on obedience to a preference for autonomy[10]. While the influence of religion on people’s lives tended to ebb and flow, strict adherence to religious authority declined.

These trends were intensified in the latter part of the 20th century. The 1960’s ushered in a period of massive cultural change in which large segments of American society became mistrustful of established institutions, values and patterns of authority[11]. The Vietnam War and the Watergate crisis engendered a lack of faith in government and established patterns of authority. The questioning of traditional social roles fueled movements seeking equality for disenfranchised individuals (e.g., African-Americans, minorities, women, persons with disabilities, gays, lesbians and transgender persons, etc.). Awareness of cultural diversity raised doubts about the universal application of unquestioned American values. The sexual revolution challenged normative constraints on sexual behavior.

In addition to extending negative liberties, America has made steady progress in fostering positive liberties. Positive liberties are the inverse of freedom from; they seek to provide individuals with the power and resources to flourish in society. Programs that extend positive liberties have included the GI Bill; Pell grants; support for education; job training; Medicaid and Medicare; Social Security; grants for scientific research, Aid for Women, Infants and Children (WIC), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and more. Although there is debate about the effectiveness of these programs, the idea that government plays a significant role in supporting the development of individual capabilities has become an important part of its ethos of liberty, justice and rights[12].

What we have gained in individual rights and personal autonomy we have lost in our commitment to moral character and public virtue[13]. As a result, there has a gradual severing of personal identity from public virtue. Social norms and moral values have come to be seen not as images that define us, but instead as external pressures that oppress us. “Morality” tends to be experienced as so many “thou shalt nots” that limit freedom and personal choice. Virtues and social values are experienced as conditions imposed upon us by some external authority, and not as ideals to which we should voluntarily aspire out of a desire to become better persons[14]. I am not so much the social values with which I identify; instead, I am the personal preferences, goals and desires that I experience when I am just being “me”[15]

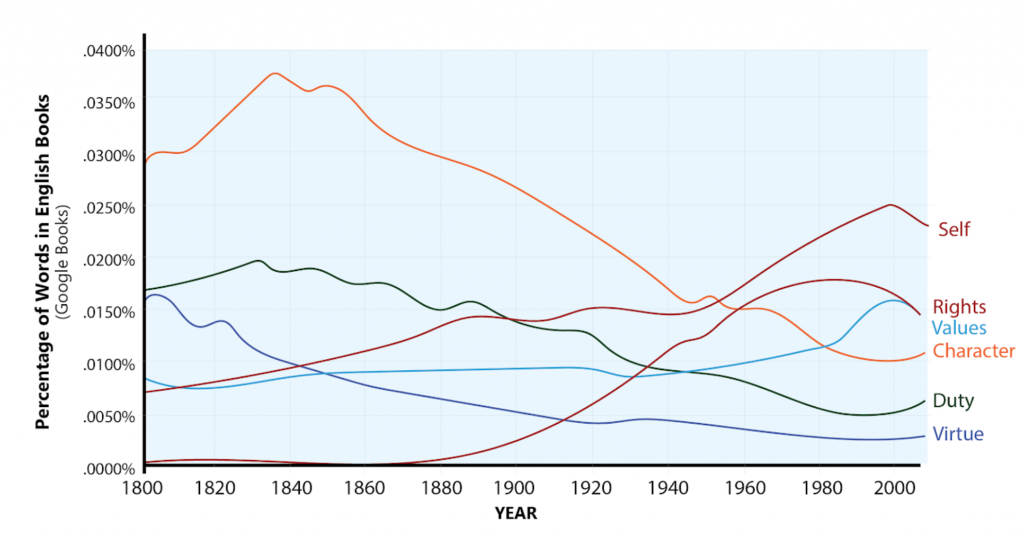

This does not mean, of course, that there is a total absence of public virtue and care; it means only that we have largely lost the social infrastructure that provides broad support for such values. It is certainly not to say that granting individual rights to varied people is a problem. It is also not to say that 18th and 19th century Americans were paragons of goodness; it only acknowledges that citizens had higher expectations of moral character in earlier times. This conclusion is supported by the Google Ngram that accompanies this page. The Ngram shows the relative frequency with which a series of morally relevant terms appeared in books written in the English language between 1800 and 2000. Since 1800, the frequency in which the terms “virtue”, “duty”, and “character” appeared declined steadily, whereas interest in “self” has steadily increased. Reference to the term “values” – often regarded as a less obligatory moral concept – began to occur in the late 1800s, and has risen ever since. Finally, references to “rights” remained steady between 1800 and 1960, and has risen steadily since that time. These trends show that terms indicating various forms of moral obligation declined in frequency over the course of American history, while terms reflecting self-related meanings increased.

Many conservative Americans have maintained a concern for character, virtue and moral values despite these shifts. However, many such groups anchor their values in absolutist moralities based on religion, authority or other essentialist beliefs. The argument made here is not that we should return to an earlier time of traditional values[16]. Traditional values were something of a mixed bag. They included values that oppress (e.g., prescriptions against divorce, birth control, and homosexuality; racism; fixed gender roles; strict obedience, etc.); values that may be worth preserving (e.g., beneficence, manners, personal responsibility, thrift, work ethic, prudence, etc.), and values subject to debate (e.g., prescriptions against single parenthood and casual sex; taste; respect for elders; patriotism, etc.). Rather than returning to glorified epoch that never existed, we should reintroduce virtue and value into our lives through deep engagement with each other, and not in ways that rely upon traditional authority.

What might a morality that coordinates rights, virtue and care look like[17]? How might we put in into practice? Let us explore this question with what currently appears to be an intractable conflict in American culture – the problem of gun violence. How can an ethos that embraces rights, virtue and care inform this issue?

We can begin by identifying gun violence as a shared problem to be solved collaboratively. One can then seek to understand how the various positions that people adopt on the issue are organized by their underlying interests, concerns, and fears. Anti-gun advocates may adopt the position that regulating the availability and distribution of guns will reduce gun violence. In invoking the familiar motto “Guns don’t kill people; people do” pro-gun advocates express the position that gun availability is not the issue. Both sides cite statistics; they may use language pejoratively, pitting “gun bigots” against “gun nuts”.

The situation begins to change once we begin to actively care about the interests of persons on the other side. Anti-gun advocates are typically interested in safety. Many (but not all) may fear guns. As a group, pro-gun advocates are interested in protecting their freedoms, families and way of life[18]. They tend to fear state intrusion onto their freedoms. While pro- and anti-gun advocates adopt starkly different positions, their interests – while different – are not necessarily in conflict. If this is so, there may be ways to address the problem that advances the interests of both sides.

Approaching gun violence as a shared problem brings together concerns about rights, virtue and care. Each side’s interest involve invocations of rights. Anti-gun advocates invoke the right to safety; pro-gun advocates draw on the second amendment. A debate over rights, however, is likely to be futile. Each side has an emotional investment in the positions they adopt. This is not a bad thing; in fact, addressing each other’s emotional investments is key to solving the problem. Instead of trying to convince the other to change, each side would try to acknowledge and meet the other’s non-conflicting interests. Instead of “Does the second amendment protect the right to bear arms?, the question becomes, “How can we ensure safety and allow gun ownership?

At this point, the ethos of care becomes prominent. If each side’s core interests do not conflict, they should be able to actively care about the interests of the other. Genuine care fosters mutual trust, which is essential for adopting an open stance toward the other. To the extent that pro-gun advocates are convinced that anti-gun advocates are interested primarily in safety and not in restricting guns per se, pro-gun advocates should be willing to seek novel solutions to the problem of safety. To the extent that anti-gun advocates believe that pro-gun advocates are committed to safety, they should be open to genuine solutions that do not require banning guns.

With these processes in place, both sides can collaborate to find novel ways to meet each other’s interests. Freed of fears about each other’s intentions, it might be possible for each side to agree that there exists a culture of violence in the United States[19]. Having identified a common problem, they can begin to take steps together to solve it. In a culture of violence people do not respect human life; they believe violence is an acceptable means toward personal ends. This is a problem of virtue and moral character. Seen in this way, might advocates on both sides to agree on the need for training in responsible gun use? On promulgating non-violent means to resolve everyday conflict? With genuine concern for the interests and values of other, improbable solutions become genuine possibilities.

When it comes to moral life, we have made an error of mistaking a part for the whole. We tend to mistake one aspect of moral life – rights and justice – for the whole of morality. When this happens, we run up against the contradiction of granting individuals the moral right to freely choose something that is beyond the purview of individual choice. Moral codes – systems of strong evaluation – neither arise naturally from within persons nor are they simply imposed from external sources. They arise, evolve and are legitimized in interactions between persons. Beyond the freedoms guaranteed by my rights, I am not free to define moral rules for myself as doing so brings me up against your experience. My violation of your boundaries raises issues of rights and justice; my sense of who I am as seen through your eyes stimulates concerns about character and moral identity; our experience each other’s pain directs us toward principles of care and compassion.

If we are to expand our moral scope, we must face obvious questions: What values should we live by? Who decides? Too often, such questions are asked rhetorically as a way of indicating their futility. However, they are only futile if we believe that our differences can only divide us. This is simply not true. Where there is difference, there also the opportunity for learning and growth. To seize such opportunities, there is a need to move beyond the idea that moral discourse can only produce winners and losers. We can make meaningful moral progress – as individual and collectives — when we come to see that we do not have to sacrifice our own values and interests in order to care about those of the other. In fact, our willingness to coordinate our values with those of the other can pave the way for the collaborate creation of novel systems of belief that resolve the initial conflicts that generated them.

References

[1] Brecher, B. (1998). Getting What You Want? A Critique of Liberal Morality. New York: Routledge.Tamney, J. B. (2005). The Failure of Liberal Morality. Sociology of Religion, 66(2), 99-120.

[2] Kesebir, P., & Kesebir, S. (2012). The cultural salience of moral character and virtue declined in twentieth century America. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 7(6), 471-480

[3] Dogan, M. (1998). The decline of traditional values in Western Europe. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 39(1), 77.

[4] Chen, Y. (2013). A missing piece of the contemporary character education puzzle: The individualisation of moral character. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 32(4), 345-360.

[5] Haidt, J., & Kesebir, S. (2010). Morality. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, G. Lindzey, S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, G. Lindzey (Eds.) , Handbook of social psychology, Vol 2 (5th ed.) (pp. 797-832). Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

[6] Taylor, C. (1989). Sources of the self. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

[7] Frimer, J. A., & Walker, L. J. (2009). Reconciling the self and morality: An empirical model of moral centrality development. Developmental Psychology, 45(6), 1669-16

[8] Bellah, R. (1994). Understanding Care in Contemporary America. In Susan S. Phillips and Patricia Benner, (Eds)., The Crisis of Care: Affirming and Restoring Caring Practices in the Helping Professions (p. 21-35). Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press; Skoe, E. A. (2013). The ethic of care: Theory and research. In B. J. Irby, et. al., (Eds.), The handbook of educational theories (pp. 615-628). Charlotte, NC, US: IAP Information Age Publishing

[9] Haidt, J., & Kesebir, S. (2010). Morality. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, G. Lindzey, S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, G. Lindzey (Eds.) , Handbook of social psychology, Vol 2 (5th ed.) (pp. 797-832). Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc

[10] Alwin, D. F. (1989). Changes in Qualities Valued in Children in the United States, 1964 to 1984. Social Science Research, 18(3), 195-236.

[11] Twenge, J. M., Campbell, W. K., & Carter, N. T. (2014). Declines in trust in others and confidence in institutions among American adults and late adolescents, 1972–2012. Psychological Science, 25(10), 1914-1923.

[12] Nussbaum, M. (2010). Creating capabilities. Belknap: Harvard.

[13] McIntyre, A. (1984). After virtue.

[14] Damon, W., & Colby, A. (2015). The power of ideals: The real story of moral choice. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press.

[15] Chen, Y. (2013). A Missing Piece of the Contemporary Character Education Puzzle: The Individualisation of Moral Character. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 32(4), 345-360.

If you like what we are doing, please support us in any way that you can.