Michael F. Mascolo, Ph.D.

As discussed in How to Have a Political Conversation about Abortion II, any political disputes can be ameliorated can be using collaborative problem-solving. Collaborative problem-solving is best suited for situations in which parties can separate the needs and interests of different parties to a conflict from broader ideological concerns. However, in most political conflicts, the interests and unmet needs of different parties are ideologically defined. Ideological differences are those that reflect differences in core beliefs, values and ways of seeing the world. Ideologies consist of beliefs about the nature of political and economic life, but also involve religious, philosophical, cultural and personal beliefs and values.

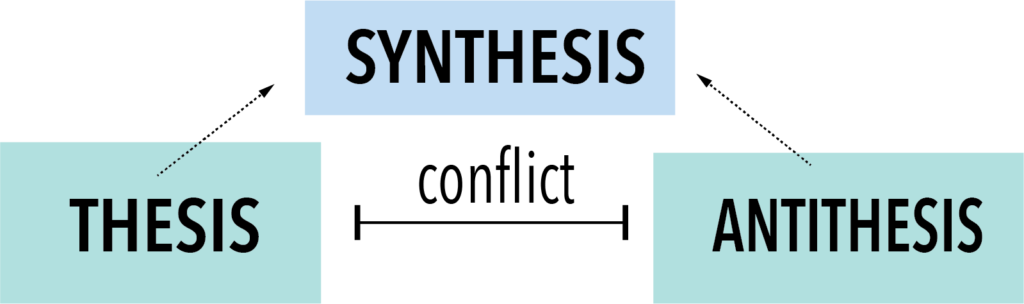

Ideological conflicts tend to be particularly intractable. However, it is possible to begin to bridge ideological divides through dialectical problem-solving. The term dialectical means thinking in opposites. Dialectical problem-solving is a way to resolve ideological differences through the integration of opposites.

We tend to think of opposites as fundamentally unbridgeable. If A and B are opposites, then they cannot both be true at the same time. Or can they? To illustrate the nature of dialectical problem-solving, consider the following fairy tale.

A prince and the princess fell in love. The king – the princess’ father — did not want the two to marry. The King said that he would only allow the couple to marry if the princess went to the Far Away Forest and perform a series of small tasks. Specifically, she had to return form the forest both walking and riding, naked and dressed, during the day and in the night, and while stopping simultaneously in and out of the castle, arrive both with and without a gift. Because it is impossible for two opposites to be true at the same time, the King was confident that the Princess would fail at each of these tasks, and thus prevent the desired marriage. After a two-week trip, the king’s daughter returned home. She arrived walking with one foot while keeping the other on a skateboard, wearing fishing net as a dress, providing the gift of a bird that flew away in the moment of passing to the King, arriving at the point of sunrise while stopping on the doorstep of the castle. The princess knew that there are often ways to reconcile seemingly contradictory statements.

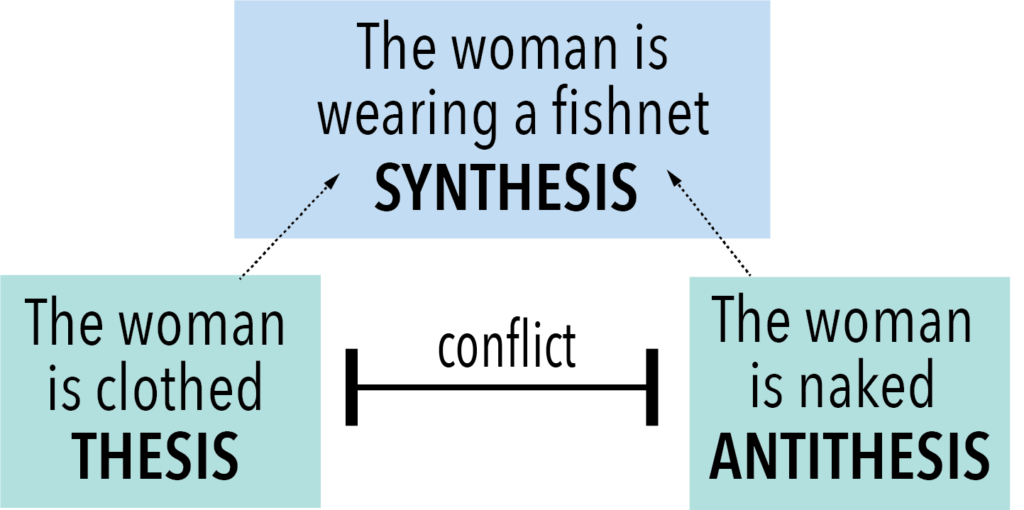

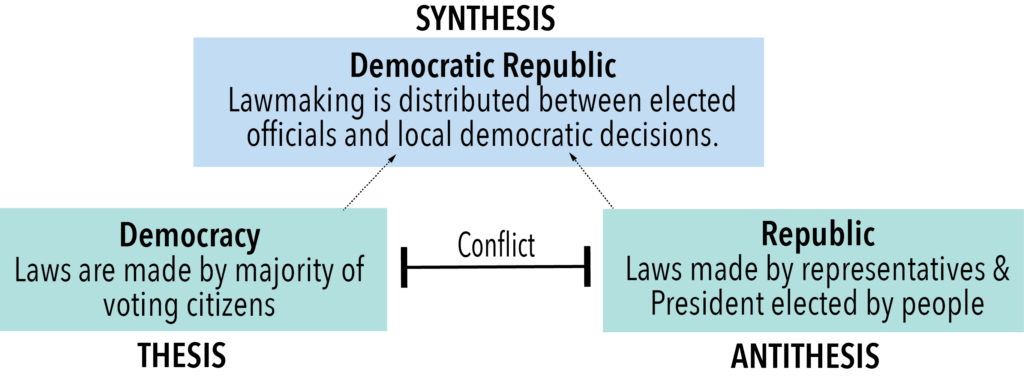

This story illustrates the basics of dialectical thinking. Seeming contradictions can often be resolved through the integration of opposites. As shown in Figure 2, at its most basic, dialectical thinking moves in a series of moments. This include thesis –> antithesis –> conflict –> synthesis. A line of dialectical thinking begins with a thesis – some initial statement (e.g., the woman is clothed). An antithesis is a statement that contradicts or negates the thesis (e.g.., the woman is naked). Together, the thesis and antithesis are in a state of contradiction or conflict.

The conflict can be removed by developing a statement that integrates the opposites in a way that resolves the contradiction (e.g., the woman is wearing a fishnet). The integration of thesis and antithesis – the integration of opposites – is called a synthesis. It is possible to think of a woman who wears a fishnet as both clothed and naked or as neither clothed nor naked. However, our understanding that the woman is wearing a fishnet resolves the apparent contradiction between “the woman is clothed” and “the woman is naked”. The dialectical resolution of this contradiction is shown in Figure 3.

Of course, one might say, we can create clever integrations of opposites in a fairy tale. How about in real life? There are many meaningful examples of how problems can be solved through the integration of opposites in everyday life. Here are but three.

The Nature-Nurture Issue

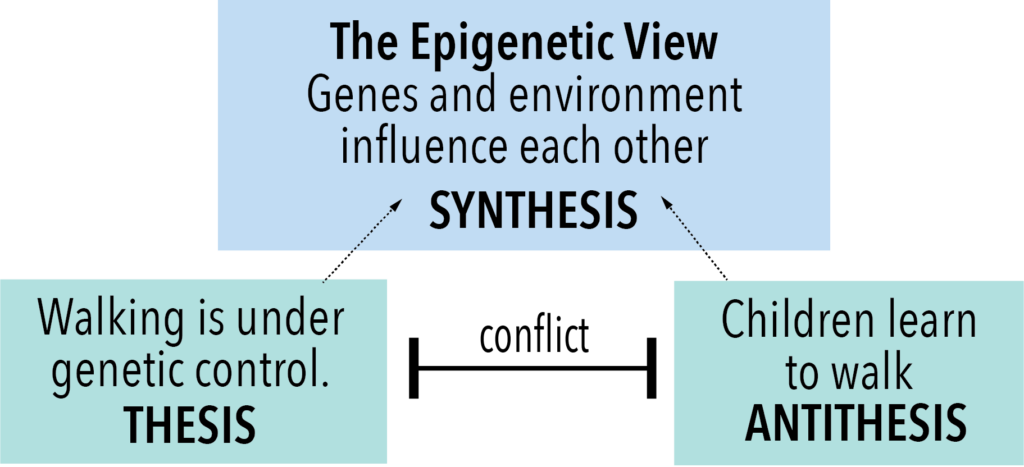

We are all familiar with the age-old nature-nurture issue: which is more important in the development of a person – nature or nurture? Genes or environment? Scientists and laypersons alike have long argued over this issue. Some have suggested (and still do) that the development of human skills and abilities are a product of genes or nature. Others suggest the opposite – that the physical or social environment was most important is the development of psychological patterns.

Let’s take a simple example. On average, children in most areas in the world begin to walk around their first birthday. Individual children, of course, differ in the precise age at which they walk. On average, girls tend to walk earlier than boys. Such findings may be taken to suggest that the thesis that the development of walking follows a genetic timetable – that the capacity for walking is under genetic control. Others suggest that the environment is most important in learning to walk. After all, children must “learn” to walk. They must actively and effortfully learn to coordinate their limbs to move from lying down to crawling to walking. Further, babies in some cultures come to sit up and walk earlier than those in Western cultures; others develop these capacities later on[i]. Environment matters.

So which is more important? Nature or nurture? The answer is, of course, neither. Neither genes nor environment cause development on their own. In fact, they are not independent: they necessarily must work together. Nature influences nurture, while nurture influences nature. Genes influence the development of bones and muscles, which enable the child greater range of motion; as the child moves, the moves, the muscles become strengthened, which enables the child to learn to sit up, crawl and eventually walk.

The idea that genes and environments influence each other is called “epigenesis”. As shown in Figure 4, the epigenetic view is the result of the integration of opposites – namely, “nature” and “nurture” views of development. Although the epigenetic view incorporates “genetic” and “environmental” views, it nonetheless resolves the contradictions between them.

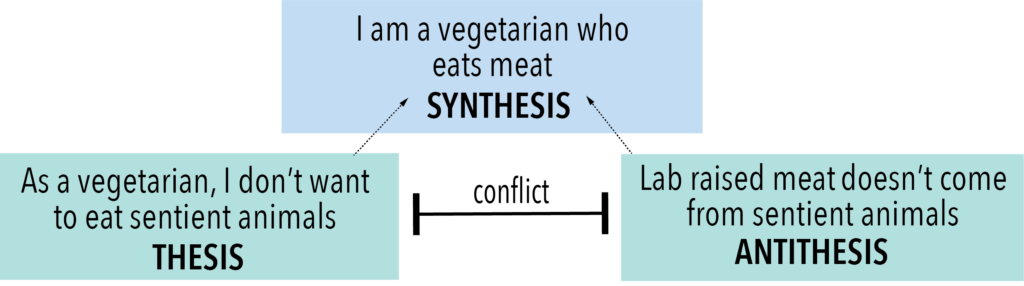

Meat-Eating Vegetarians

A “vegetarian” is a person who does not eat meat. There are many reasons for opting for a vegetarian diet. These include issues related to health, preserving the environment, or even simply not liking meat. Some vegetarians do not eat meat because they do not want to eat animals who are sentient and can feel pain. Let us call statement a thesis.

It is now becoming possible to produce cell-based “meat” in the laboratory[ii]. Cell based chicken, beef or pork is made for animal cells that are cultivated outside of the animal’s body. Such products are likely to remove the main objections to eating meat for vegetarians who are uncomfortable kill sentient animals. It thus becomes possible for some people who identify themselves as vegetarians who nonetheless eat meat.

Forms of Government

A government is a system for influencing, directing or controlling the activities of a state. There are many forms of government. The United States is often understood as a democracy, but it is more appropriate to say that the United States government is a democratic republic. A democratic republic is run under principles of both democracies and republics. The two forms of government are similar. A democracy consists of government by the people. A republic is government that in which laws are made by elected representatives who are constrained by both a constitution and an elected President.

A democratic republic combines aspects of both a democracy and a republic. Note that in any synthesis, both thesis and antithesis must be modified in some way to form the synthesis. In the case of a democratic republic, a pure democracy is modified by having elected representatives engage in lawmaking; a republic is modified because some decisions – particularly at the local levels – are made by the people themselves (e.g., referendums, town meetings, etc.).

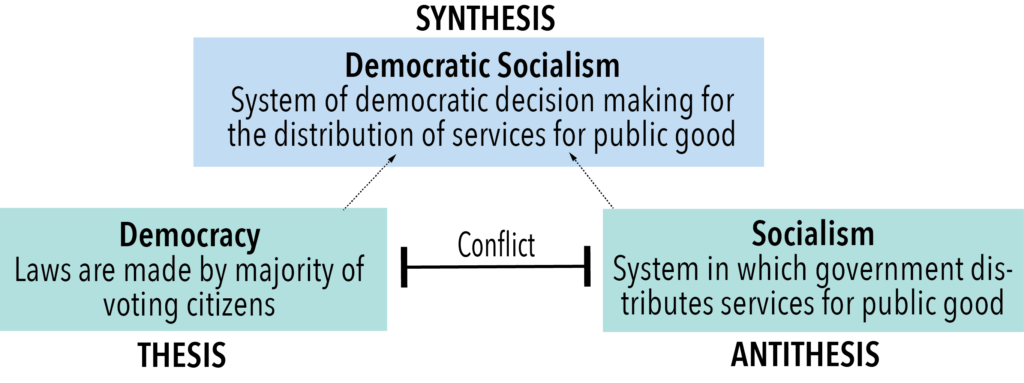

A more recent attempt to reconceptualize democratic government comes in the form of democratic socialism. For many, the terms democracy and socialism are contradictory terms. Democracy refers to a form of government by the people; socialism typically refers to an economic system involving some sort of centralized control. To resolve this contradiction, democratic socialism consists of a form of government which exerts democratic decision-making about the distributions of goods and services to the public.

Where collaborative problem-solving works by separating the problems that parties are trying to solve from broader ideological commitments, Dialectical problem-solving works by engaging ideological divides directly. Although there are multiple steps in the process, the core process involves seeking to construct novel shared beliefs through the integration of opposites. At base, this involves

While a detailed illustration of dialectical problem-solving is beyond the scope of this article, it is possible to provide a taste for how the process occurs. Let us do so by extending the example of abortion. A common ideological difference between so-called “pro-life” and “pro-choice” proponents concerns the question of the status of the unborn fetus. Many conservative and religious advocates of the so-called “pro-life” position argue identify the single celled fertilized egg as a person. At the other extreme, some progressivists would suggest that while the fetus is a potential person, it does not gain personhood until much later – until birth or thereafter. Moderate positions suggest various ways of demarcating when a fetus can be considered to have the qualities that would render it worthy of being protected from harm.

1. Understanding the Other. The first step of dialectical problem-solving begins with cultivating a mutual and credulous understanding of conflicting ideologies. One approach to the pro-life position builds on religious beliefs. From this view, things in the world have essences that are determined by a divine source. The fetus is a human person with all the privileges of personhood from conception. The alternative view, independent of religion, states that human life develops over time in utero. As a result, it is unclear when the fetus becomes a person with the moral status we assign to personhood.

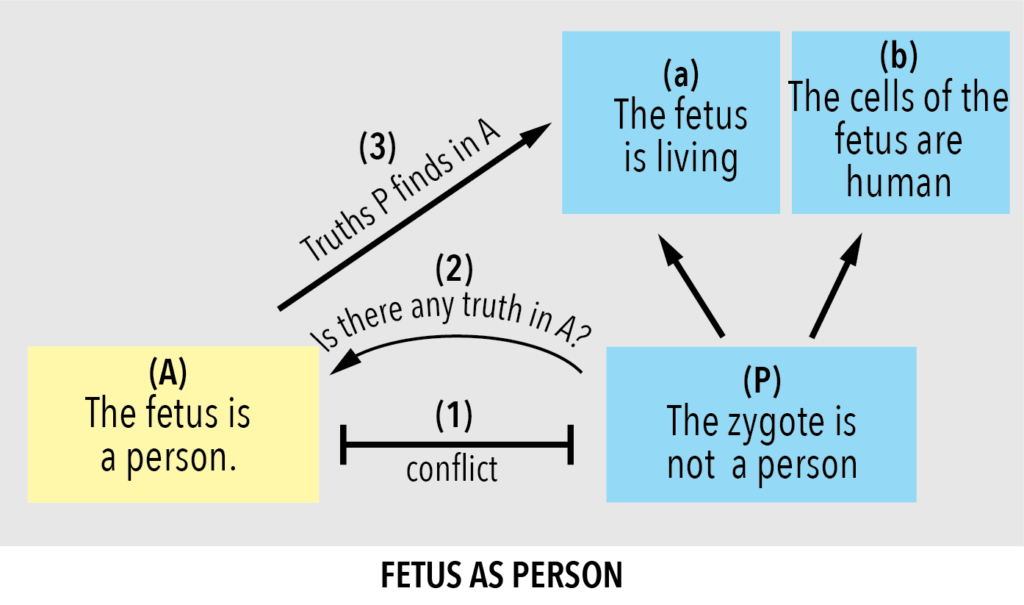

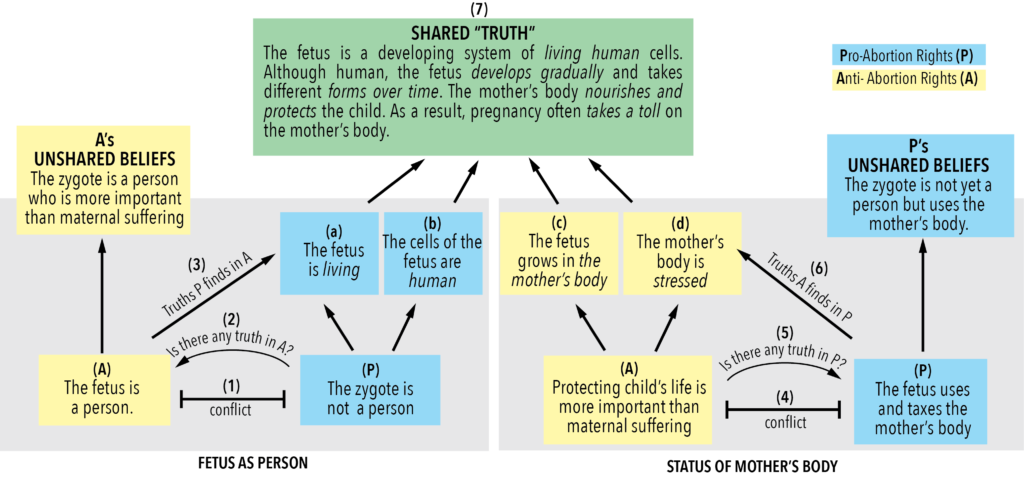

2. Identifying Kernels of Truth. This is, perhaps, the most important step. Each participant is asked to find a kernel of truth – however banal or seemingly trivial – in the beliefs of the other. For example, the pro-choice advocate can be asked to reflect on the question, “Is there any ‘kernel of truth’ in the statement, ‘the fetus is a person’”? The process of addressing this question might look like this:

We start at Point (1) with the core conflict between the two positions: Andy says that the fetus is a person, while Penelope denies this. Penelope is then asked to seek to identity any (2) “kernels of truth” in Andy’s position. Although Penelope does not agree that the fetus should be considered a person, she can agree that the (3) fertilized egg is composed of (a) human cells that are (b) living.

A good faith exchange might include something like this:

| ANDY: Can you find any truth at all in the statement that “a fetus is a person”? | |

| PENELOPE: I can agree that the fertilized egg is made of cells that are human, that is, human cells. These cells will eventually develop to become a person or child. I can also agree that these cells, of course, are living. |

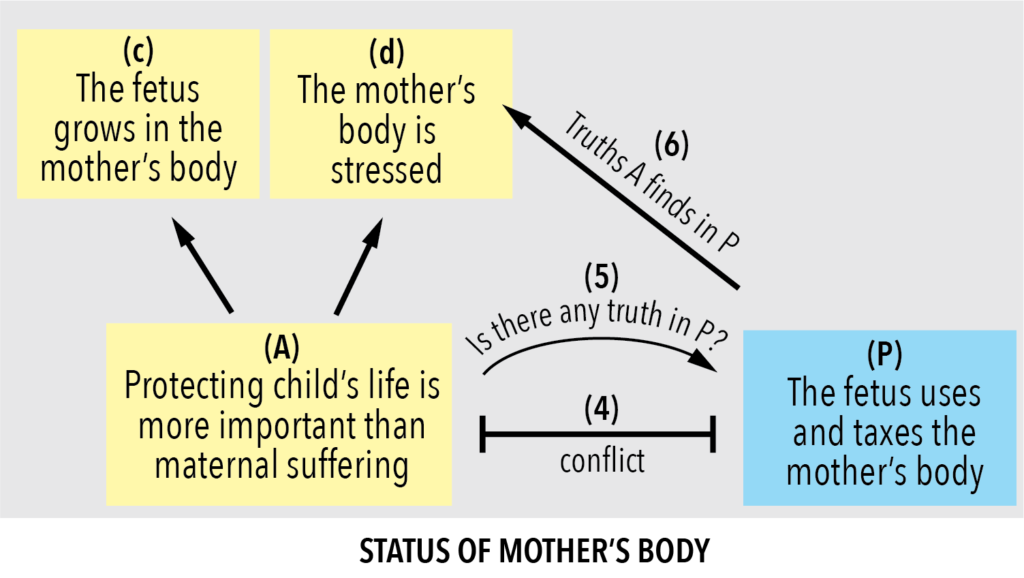

Continuing the conversation, an anti-choice advocate might be asked, “Can you find any truth in the statement that the mother has a right to control the use of her body? That pregnancy taxes and puts a strain on the mother’s body?” The process might look something like this:

Continuing the process described above, the conversation would begin at Point (4) with a contradiction between Penelope’s statement that “the mother has a right to control the use of her own body” and Andy’s statement that “protecting the child’s life is more important than the mother’s suffering”. When asked to find (5) any “kernels of truth” in Penelope’s statement, Andy is able to agree that (6) because the fetus indeed grows in the mother’s body, it places a stress on her body.

A good faith exchange might look like this:

| PENELOPE: Can you find any truth at all in the idea that the mother has a right to exert control over the use of her body? That the pregnancy places a strain on the mother’s body and changes it? | |

| ANDY: Well, of course the fetus grows in the mother’s body. And yes, the mother’s body is changed by being pregnant. The mother’s life can be threatened as well. But the developing infant is more important than the mother’s suffering. And the mother – most of the time, chose to have sexual relations which lead to pregnancy. |

In this brief exchange, Andy was indeed able to find “kernels of truth” in Penelope’s statement. But he also expressed other anti-abortion opinions as well (e.g., the fetus’ life is more important than maternal suffering). While the intent of this step is to identify areas of agreement, it is typically difficult focus only on agreement when strong feelings are involved. When this happens, the job of the problem-solvers is to separate areas of agreement from disagreement. Areas of disagreement will remain, and are topics to be discussed after areas of agreement can be created.

3. Mutually Adjusting Beliefs. Once “kernels of truth” are identified in the positions of one’s interlocutor, the question can then become, “How, if at all, might my overall thinking about this issue change as a result of acknowledging these truths?” At the early stages of discussion, the types of “truths” found in the other are likely to be subtle. As a result, they may or may not motivate partners to modify other existing beliefs in light of these “truths”. At initial stages, creating areas of agreement can engender trust, foster confidence that it is possible to create common ground, and pave the way for further discussion.

Nonetheless, even minor areas of agreement can foster reflection that can lead to the modification of existing beliefs. For example, a pro-abortion rights advocate who acknowledges the fetus as a form of human life might be open to reflecting upon what makes the fetus a “human” life, and when ‘human cells” begin to take on the qualities of personhood. Alternatively, an anti-abortion right advocate who is able to acknowledge the effect that a pregnancy has on a mother’s body may be more likely to take the mother’s sufferings into account when making judgments about the circumstances under which women can and should have control over how they use their bodies.

4. Constructing Novel Partially Shared Beliefs

As parties adjust their own beliefs, it may become possible to develop novel, partially shared beliefs between social partners. At the very least, participants can identify the “kernels of truth” that they have identified in each other and coordinate them into a novel and shared belief. To illustrate, Figure 11 shows the full course of dialectical problem-solving for our hypothetical example:

As shown in Figure 10, through dialectical problem-solving, our hypothetical dyad was able to identify the first step in the development of shared beliefs:

The fetus is a developing system of living human cells. Although human, the fetus develops gradually and takes different forms over time. The mother’s body nourishes and protects the fetus as it develops. As a result, pregnancy often takes a toll on the mother’s body.

This shared belief shows what both parties are able to agree upon. Both partners must be free to identify continued areas of non-agreement. In fact, the capacity to identify nonshared beliefs is central to the process of creating common ground: it allows each party to identify the boundaries of their shared beliefs. It ensures that neither party is pressured to “give in” or agree to a statement that they do not believe in. In this way, the capacity to identify what is not agreed upon allows the parties to identify what they can agree upon. Discussions of areas of disagreement await dialectical conversations at another time.

In early phases of dialectical problem-solving, development is likely to be modest. However, shared beliefs set the foundation for further development. More important, even modest agreements hold out a promise that some degree of common ground can be constructed.

[i] https://www.sciencenews.org/article/culture-helps-shape-when-babies-learn-walk.

If you like what we are doing, please support us in any way that you can.