Protests are occurring in American universities over the war in Gaza. Administrators at many campuses have sought to remove protesters from campus – often citing concerns about security and safety. However, it is difficult to resist the sense that administrators are also afraid of the consequences of appearing to tolerate antisemitism on campus.

The President of Columbia called on police to remove protesters from Columbia’s campus. Other administrators have followed suit. There have been reports of police using force against students and professors. An Emory economics professor was forcibly thrown to the ground and handcuffed by two police officers. A video of this incident can be found here.

Universities have both the right and responsibility to keep their students physically safe. Students are expected to follow campus rules for peaceful assembly. If they violate those rules, universities have the right to take action.

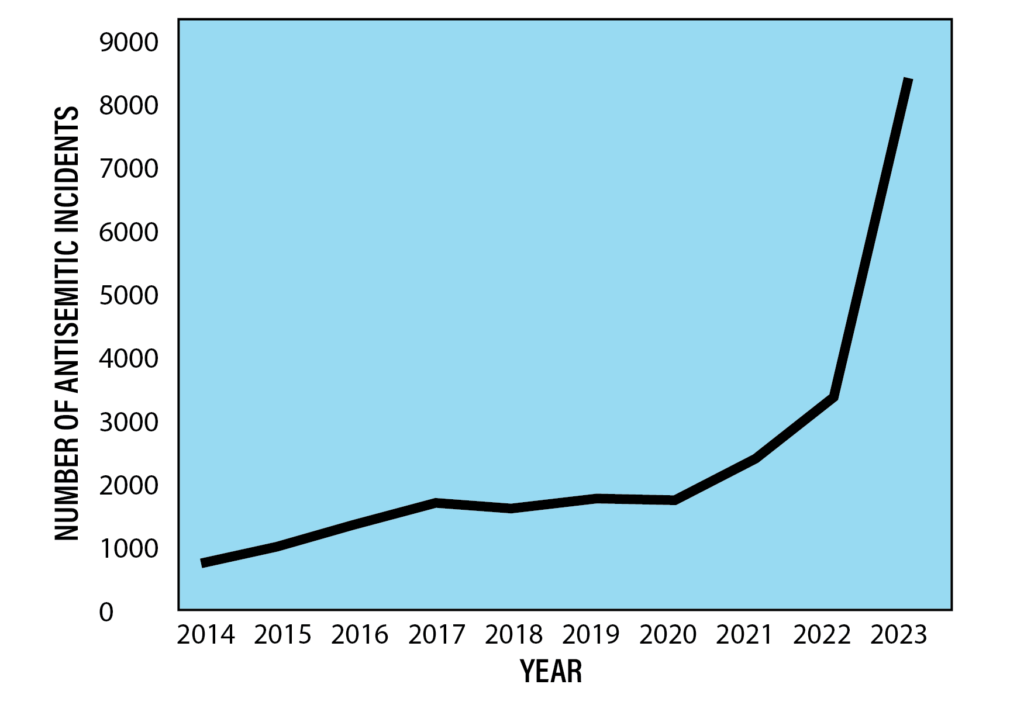

However, much of the criticism of the protests concerns statements made by students and faculty would some regard as antisemitic. Charges of antisemitism must be taken seriously. Indeed, rates of antisemitism have increased exponentially over the past year. Figure 1 shows changes reports of antisemitic incidents over the course of a 10-year period. The figure shows a gradual increase, that rises precipitously in 2023.

Figure 1. Increases in Incidents of Antisemitism Over a 10-Year Period.

(Adapted from Anti-Defamation League, 2024).

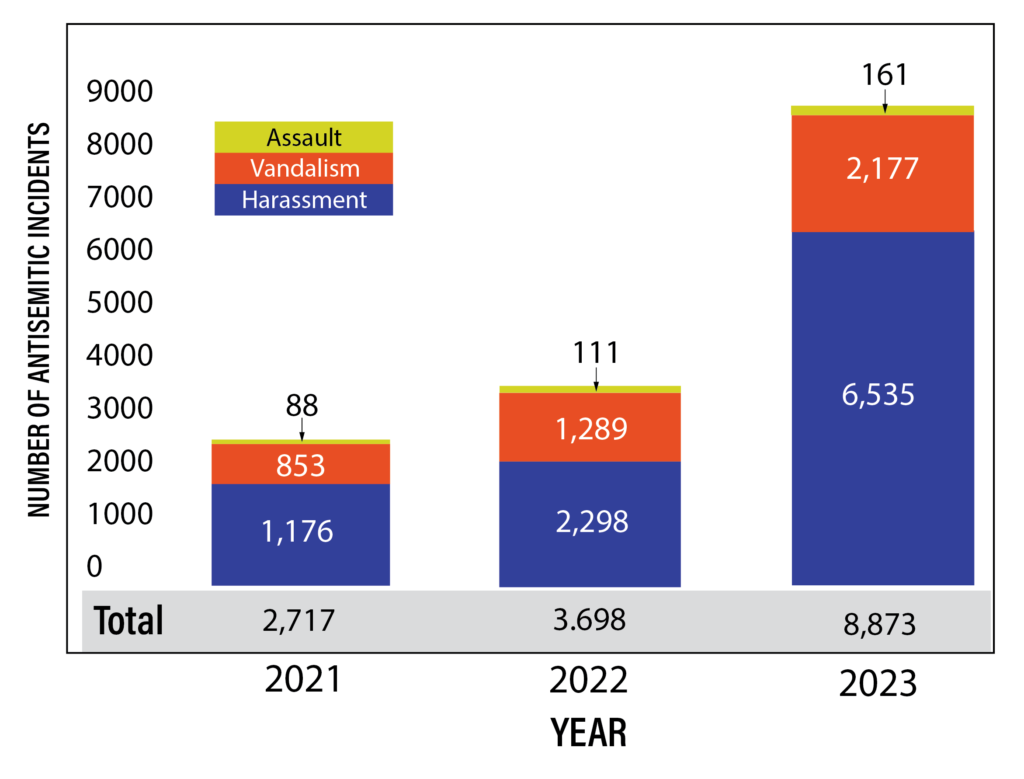

Figure 2 breaks down these incidents by type. The largest proportion of antisemitic incidents involve harassment, followed by vandalism and acts of violence. These changes shown in Figures 1 and 2 are both dramatic and disturbing. They reflect the rising level of strife and political polarization that we are currently experiencing.

Figure 2. Breakdown of Antisemitic Incidents by Type from 2021-2023.

(Adapted from Anti-Defamation League, 2024).

What Counts as Antisemitic?

Antisemitism is a serious issue. However, there is no consensus about the definition of this important term. Here are three prominent definitions:

Antisemitism is the marginalization and/or oppression of people who are Jewish based on the belief in stereotypes and myths about Jewish people, Judaism and Israel (Anti-Defamation League, 2020)[i].

Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities (International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, 2016/2024)[ii]

Antisemitism is discrimination, prejudice, hostility or violence against Jews as Jews (or Jewish institutions as Jewish) (Jerusalem Declaration, 2024)[iii]

As we can see, these definitions differ in important ways. The Anti-Defamation League defines antisemitism broadly. Acts are seen as antisemitic if they “marginalize” or “oppress” people based on “stereotypes” and “myths” about “Jewish people, Judaism or Israel”. This definition allows considerable interpretation: what counts as marginalization or oppression? How stereotypical does a characterization have to be before it is considered antisemitic? When does an interpretation take on mythic status? Should acts leveled at Israel – rather than Jews per se – be regarded as antisemitic?

The definition put forth by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance is also broad. It includes a list of 11 examples of antisemitism (see Appendix A for the entire list). Among these acts include:

These particular stipulations run the risk of defining mere opinions about the state of Israel as inherently antisemitic. For example, it at least possible for Jewish person to claim greater fealty to Israel than to their native lands. Would calling attention to such an act, if it were to occur, be antisemitic?

I suggest that the Jerusalem Declaration’s (2024) definition of antisemitisms as “discrimination, prejudice, hostility or violence against Jews as Jews” best identifies the core of antisemitism. Here, antisemitism refers to prejudice against Jews because of their Jewishness. In this way, antisemitism is linked to the concept of essentialism – that there is something necessary or essential about what it means to be a Jew, and that this “essence” is in some way inherently inferior, hateful or evil.

When Does it Become Antisemitic?

It is important to differentiate antisemitic statements from other controversial or critical statements that might appear antisemitic but are not. Making such differentiations serves both defenders and critics of Israeli policy and actions.

Drawing on the Jerusalem Declaration definition of antisemitism, Table 1 differentiates antisemitic remarks from other forms of critical remarks. The columns differentiate critical remarks based on their focus – that is, what or whom the remark is directed toward. As indicated in the table, a remark can be directed at (a) Jews as a religious or cultural group (i.e., Jews as Jews), (b) Zionism (the process of seeking a state for Jews in their ancestral homeland) or (c) the policies and actions of the Israeli government.

The rows of the table identify different types of statements. A remark can express (1) an essentializing bias (attributing a negative essence to the entity in question), (2) an evaluation (expressing positive or negative opinion about the entity), or a (3) description (a more-or-less non-judgmental or “fact-based” account) of the entity in question.

Table 1

How to Differentiate Antisemitism from Other Types of Critical Remarks

| FOCUS OF REMARK | |||

| FORM OF REMARK |

Religious/Cultural |

Zionism |

State/Policy |

| Essentialist | Eliminate the Jews from the river to the sea

“Jews control the world” “Jews have bold, misshapen noses”[iv] |

“There is no reason for Zionists to live”[v]

|

“Kill Israel and the Jews”[vi]

|

| Evaluative | Orthodox Jews restrict the rights of women

Jews tend to be highly educated “Authentic Jewish food does not exist”[vii] |

“Zionism is racism.” [viii]

“I am “unalterably opposed to political Zionism.”[ix] “Palestinians [were displaced] from their lands by the Zionist project…”[x] |

“Why the Israeli state is racist to the core”[xi]

“From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free””[xii] “This is not ‘Netanyahu’s war’, it is Israel’s genocide”[xiii] “Israel has no right to exist.”[xiv] |

| Descriptive | Jews are well represented in the garment industry

Most American Jews are Democrats[xv] As a group, Jews teach higher education levels than other religious groups[xvi] |

Zionism is the movement for the self-determination and statehood for the Jewish people in their ancestral homeland[xvii]

Republicans tend to support Zionism more than Democrats.[xviii] |

Over 34,000 Palestinians have died in the war[xix]

“In October, Israel intensified its 16-year blockade on Gaza, cutting off all supplies, including food, water, electricity, fuel and medicines”[xx] |

Antisemitic remarks are those that characterize the religious and cultural identities of Jews as either individuals or collectives using essentializing biases of a negative or dehumanizing nature. This category of remarks is shown in the upper left hand (darkly shaded) cell of Table 1. Examples of such remarks include admonitions to violence (e.g., “Kill the Jews”, “Eliminate Jews from the river to the sea”), essentializing descriptions (e.g., “Jews control the world”) or negative stereotypes seen as essential to all Jews.

Remarks in the upper left category are the only examples of genuinely antisemitic remarks. Remarks that are critical of Zionism are different from those that are directed at Jews as Jews. It is possible to be critical of the idea of an ancestral homeland without holding essentializing prejudices towards Jews. Similarly, remarks that are critical policies of the Israeli government are different from those directed as Jews as Jews. It is possible to disapprove of actions of the Israeli government without believing in hold essentializing prejudices toward Jews as Jews.

The idea that anti-Zionist and anti-government remarks are not the same as antisemitic remarks does not mean that all anti-Zionist and anti-government remarks are acceptable. They are not. Calls for the killing or elimination of Zionists or the Israeli government – while not formally antisemitic – should be regarded as unacceptable forms of speech. This is because they (a) call for violence against others based upon (b) essentializing characteristics of the group in question (e.g., Zionists as Zionists; government officials as government officials). For example, recently, a 20-year-old Columbia student announced his views that “There is no reason for Zionists to live.” This is a form of essentializing speech calling for violence against Zionists. Thus, such forms of speech may be regarded as unacceptable, but not because they are necessarily antisemitic.

The second row of Table 1 shows a series of (non-essentializing) evaluations. Evaluations may be controversial, contestable, and even offensive – but they should not be regarded as antisemitic or unacceptable. Regardless of whether one may agree or disagree that “Orthodox Jews restrict the rights of women”, “Zionism is racism”, or “The Israeli government is racist to its core”, in an open society, people should be entitled to evaluate the practices of other individuals and groups – even if some may regard those evaluations as offensive.

Context matters. Consider the phrase “from the river to the sea”. Many regard this statement as inherently antisemitic. However, people use the same language express many different meanings. To be sure, the phrase “Kill all Jews from the river to the sea” is clearly antisemitic. However, the phrase, “From the river to the see, Palestinians will be free” need not be. Many explicit use this phrase to refer merely to the rights of Palestinians to be free from what they take to be Israeli oppression. Such a statement is not inherently antisemitic.

And so, it is not possible, of course, to identify precise criteria that unambiguously differentiate antisemitic from non-antisemitic remarks. The boundaries that separate antisemitic from non-antisemitic forms of speech will necessarily be blurry. Phrases like “Zionism is racism” or “The Israeli state is racist to the core” may straddle the boundary between essentializing biases and evaluations. Again, context matters.

The third row of Table 1 contain a series of descriptive statements directed toward Jews, Zionists and Israel itself that. Even when they appear to be critical, because they are intended to be non-essentializing descriptions of actually occurring conditions, they should neither be regarded as antisemitic nor unacceptable forms of speech.

Against Antisemitism but For Free Speech

Many who have expressed criticism of Israeli policies – including students and faculty in university protests — have been criticized as being antisemitic. Charges of antisemitism are powerful ones – they quickly function to discredit the person who uses such epithets. However, extending “antisemitism” beyond its core definition risks rendering the concept of antisemitism inert. When expanded definitions of antisemitism are used as a tool for quelling critical or controversial speech, charges of antisemitism – legitimate or otherwise — begins to lose their force. Simultaneously, they can function as vehicles for limiting free speech and the exploration of ideas.

A better approach is to clearly identify what one takes to be antisemitic and to seek to differentiate genuinely antisemitic remarks from those that are merely critical of beliefs, actions, and policy. There is no contradiction between fighting antisemitism and protecting free speech.

Appendix A:

Examples of Actions Considered Antisemitic by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance

[i] Anti-Defamation League (2020). A Brief History of Antisemitism. https://www.adl.org/sites/default/files/brief-history-of-antisemitism.pdf.

[ii] International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, 2016/2024, https://holocaustremembrance.com/resources/working-definition-antisemitism

[iii] Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism, 2024, https://jerusalemdeclaration.org

[iv] Herzl, T. (1960). The Complete Diaries of Theodor Herzl, Rapha Patai (Ed.), Harry Zohn (trans.). Herzl Press and Thomas Yoselo, cited in Massad, J. (2005). The Persistence of the Palestinian Question. Cultural Critique, 59, 1–23. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1353/cul.2005.0009

[v] Rosman, K. (2024, April 16). “Columbia Bars Student Protester Who Said ‘Zionists Don’t Deserve to Live’”, New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/26/nyregion/columbia-student-protest-zionism.html

[vi] Anti-Defamation League (2023). “Audit of Antisemitic Incidents, 2023”, https://www.adl.org/resources/report/audit-antisemitic-incidents-2022

[vii] Katz, J. P. (2017). “Jews are What We Eat. And We Eat Everything”. Jewish Currents. https://jewishcurrents.org/authentic-jewish-food-does-not-exist

[viii] American Jewish Committee, (2024). “Zionism is Racism”, https://www.ajc.org/translatehate/Zionism-is-racism

[ix] Tracy, M. (2021, November 2). “Inside the Unraveling of American Zionism”. New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/02/magazine/israel-american-jews.html

[x] Al Jezeera, (2017, May 14). “The Nabka did not start or end in 1948”, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2017/5/23/the-nakba-did-not-start-or-end-in-1948

[xi] Kimber, C. (2023). “Why the Israeli State is Racist to the Core”. https://socialistworker.co.uk/features/why-the-israeli-state-is-racist-to-the-core/

[xii] Sternfield, M. (2024, April 26). “Is ‘From the River to the Sea’ Hate Speech?” KTLA, https://ktla.com/news/california/what-does-from-the-river-to-the-sea-really-mean/

[xiii] Ibsais, A. (2024). “This is not ‘Netanyahu’s war’; It’s Israeli genocide”, Al Jazeera, https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2024/3/7/this-is-not-netanyahus-war-it-is-israels-genocide

[xiv] Leary, J. P. (2024, January 3), “Israel’s ‘Right to Exist” is a Rhetorical Trap”, The New Republic. https://newrepublic.com/article/177768/israel-right-to-exist-rhetorical-trap

[xv] Pew Research Center (2021). “Jewish Americans in 2020”, https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/05/11/jewish-americans-in-2020/#:~:text=Pew%20Research%20Center%20estimates%20that,were%20Jews%20of%20no%20religion.

[xvi] Pew Research Center (2016). “Jewish Educational Attainment”, https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2016/12/13/jewish-educational-attainment/#:~:text=With%20an%20average%20of%2013.4,%25)%20has%20post%2Dsecondary%20degrees.

[xvii] Anti-Defamation League (2016). Zionism. https://www.adl.org/resources/backgrounder/zionism

[xviii] Telhami, S. (2023, July 18). “How Do Americans feel about Zionism, Antisemitism and Israel?” Brookings, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-do-americans-feel-about-zionism-antisemitism-and-israel/

[xix] Reuters, (2024, April 28). “World Central Kitchen to resume Gaza aid after staff deaths in Israeli strike”, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/world-central-kitchen-resume-gaza-aid-after-staff-deaths-israeli-strike-2024-04-28/

[xx] Amnesty International (2024). “Israel and Occupied Palestinian Territories 2023” https://www.amnesty.org/en/location/middle-east-and-north-africa/middle-east/israel-and-occupied-palestinian-territories/report-israel-and-occupied-palestinian-territories/

If you like what we are doing, please support us in any way that you can.