Mark Twain’s doctor said that if Twain were to give up smoking, he could add 10 years to his life. Twain is reputed to have said, “Who wants to live 10 years longer if you can’t smoke?”

Whether the story is true is not important. What is important is understanding that saying something is “bad” is an evaluative judgment. Something can be bad for one’s health – like smoking – but we can still value it for other reasons. Twain’s comment suggests that he valued smoking more than the 10 years he could have gained from not smoking.

Science can tell us whether being overweight or obese is bad for one’s health. However, having that knowledge, the question of how to live remains a personal one.

With that said, let’s asks, is being fat bad? Many advocates of the “fat acceptance” movement would say, “no”. The “fat acceptance” movement is born of noble intentions. It seeks to reverse the stigma associated with being “fat”. It wants to eliminate bias, disrespect and discrimination that people who are considered overweight or abuse experience. These are, of course, good things. But there is a difference, I suggest, between honoring the dignity of people who are “fat”, “overweight” or “obese” — and believing that “fatness” itself is good.

Being Fat Doesn’t Make You Bad

In a recent article, I addressed the question, “Does Being Fat Make You Bad?” The answer, I argued, was “no”. My point there was to try to show that “being fat” has nothing per se to do with being a good or bad person. My point was that there is no contradiction between wanting to lose weight and accepting oneself as a person who has difficulty maintaining one’s desired weight. In fact, I argue, self-acceptance without shame is necessary if we are to move forward to develop the discipline that we need to change our lifestyle in ways that promote bodily health.

The point is that if we want to improve our lives – in any way – we must be able to accept who we are now with all of our challenges and struggles. We should not think of ourselves as fixed beings; instead, we should think of ourselves as always under development. And that means accepting the good and not-so-good about who I am now so that I have the courage to build a better version of myself without experiencing a threat to my self-esteem.

But is Being Fat Bad?

Now, the question “Does Being Fat Make You Bad” is different from the question of whether being fat is good or bad. Many in the “fat acceptance” movement tend to suggest that there is nothing bad about being fat, overweight or obese. Such people argue that the negative judgments that people have about being fat are merely a matter of prejudice. For example, Virginia Sole-Smith, a leading advocate of “fat acceptance,” speaks of the “myth of the childhood obesity epidemic”. For her, the problem is not so much the rising weight in youth, but instead “anti-fat bias: the hatred of fatness that results in the stigmatization of fat people in almost every realm of society.”

McPhail and Orsini (2021) extend this argument:

Scholars of fat studies understand fatness as a way of thinking about bodily diversity. This literature maintains that fatness should be uncoupled from pathology, as such framings attach fatness to a sense of moral weakness and failed citizenship, and can fuel stigma in various settings, even health care. Such an uncoupling is increasingly supported by medical and population health research, which suggests that people who are labelled obese are not necessarily unhealthy.

And still further, McHugh and Kasardo (2015) write:

The medicalization of fat as “obesity” and the subsequent war on obesity endorses dieting and suggests that weight can be controlled through caloric management and exercise, which gives people permission to demonstrate hostility and discrimination against fat women who appear to have refused to diet or seem to be too lazy to exercise. Contrary to popular opinion, and in many cases mistaken medical opinion, scientific evidence continues to demonstrate that, for the most part, weight is not within the control of an individual.

What’s Right and What’s Wrong in the Fat Acceptance Movement

The “fat acceptance” movement has noble goals. Advocates of fat acceptance decry the stigmatization, bullying, and shaming of people whose bodies do not conform to social ideals. They want to forestall discrimination against people who are considered overweight or obese. These are noble sentiments to which all decent people, I think, should aspire.

Is there an Obesity Epidemic? There are serious questions about the claims made by advocates of the “fat acceptance movement”. Let’s start with the claim made by the medical community that there is an obesity epidemic. As indicated above, Sol-Smith (2023) rejects this idea, suggesting that the concept of “epidemic” pathologizes fatness and that it is social norms and not body mass that must change. Similarly, McPhail and Orsini (2021) hold that obesity should not be considered a “pathology”.

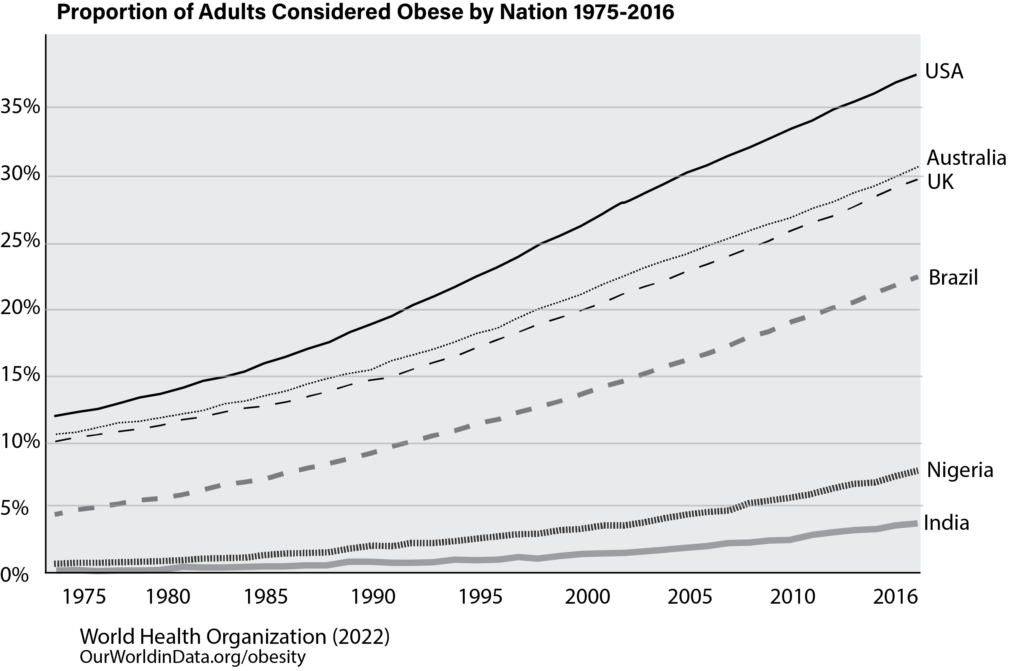

First, regardless of what terms we use to refer to weight and body mass, there can be no doubt that on average, people have become heavier over the past century – and particularly over the past 50 years. The data are clear. Here is a graph that shows the increase in levels of obesity – defined in terms of body mass index, since 1975 across different nations.

Figure 1. Proportion of Adults Classified as Obese Over Time in Different Nations

There is some controversy about how best to define “obesity”. For the present purposes, this doesn’t really matter. One can vary the definition to be more restrictive or liberal – the graph will be basically the same (although shifted upward or downward). Mean weight has increased steadily over time. Different nations exhibit different trends. This means that the phenomenon of increasing weight is real – and that the differences over time are not due to factors that are “uncontrollable”. The fact that average weight has increased over time and that the effect differs by nation means that something beyond “genetics” is occurring.

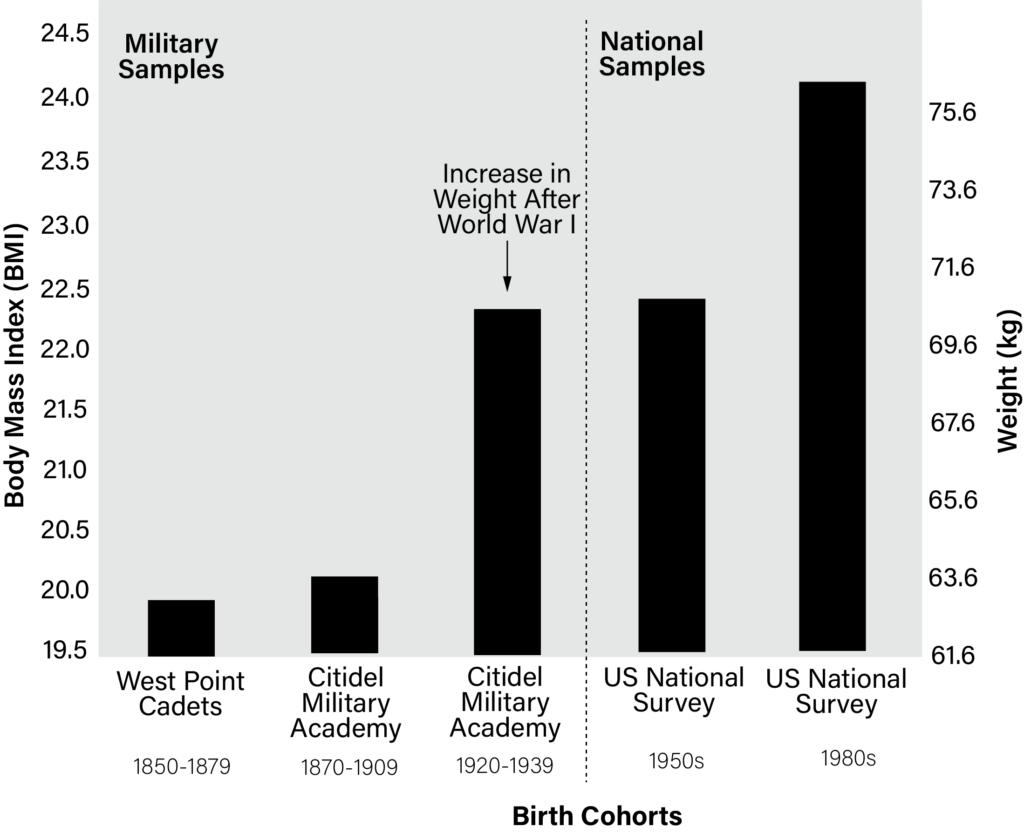

Komlos and Brabec (2010) provide convincing evidence that the trends in obesity began well before 1975. Here are some data that show how the mean body mass index for 18-year-old White males began to increase after World War I.

Figure 2. Changes Body Mass Index and Weight for 18-year-old White Men since 1850. National data on body mass and weight for all Americans were not collected until the late 1950’s. The left reports data for 18-year-old White men from available military samples. The data on the right are national samples of 18-year-old white men. Men who applied to military academies during the 1800’s were quite thin indeed! An increase in weight occurred after World War II. The data for the general sample shows the increase in weight from the 1950’s onward. Adapted from Komlos and Brabec (2010).

Regardless of the standards we use to define weight, there is no doubt that average weight has increased over the past century. Regardless of whether one wishes to use the medicalized term “epidemic”, the rise in weight is dramatic.

Does Obesity Cause Health Problems? Members of the “fat acceptance” movement sometimes suggest that the health effects of obesity are overstated. For example, Sol-Smith (2023) states that “there is a chicken-and-egg style conundrum underpinning every part of it. We don’t’ have concrete data showing that a high body weight causes health problems like diabetes, heart disease, and asthma. This is, at best, a correlating relationship”. Similarly, McPhail and Orsini (2021) suggest that medical professionals increasingly agree that “people who are labelled obese are not necessarily unhealthy”.

Let’s unpack these statements. First, McPhail and Orisini (2021) are correct in their claim that medical professionals imply that obesity does not necessarily imply lack of health. Medical professionals are questioning the thresholds used to define obesity using the body mass index. They also agree that moderate levels of what is currently considered obesity are not necessarily unhealthy. Still further, there is evidence that some people who are considered obese can also be regarded as physically fit.

Nonetheless, the evidence that links obesity to health problems is simply overwhelming (Dixon, 2010; GBD Global Collaborators, 2015; Lam et al., 2023; Reilly et al, 2003). Sol-Smith suggests that the evidence is flawed because the evidence is based on correlational studies that cannot establish direct cause-and-effect links. Sol-Smith is certainly right if she wants to urge caution. Correlations simply note that two events are related. For example, people who are classified as obese have higher levels of heart disease. This is a correlational statement. However, as the maxim goes, “correlation does not imply causation”. The fact that people who are obese have higher levels of heart disease does not necessarily mean that obesity causes heart disease. It could be that something else causes both obesity and heart disease. For example, person’s genetic dispositions may “causes” both obesity and heart disease; in this case, the link between obesity and heart disease would not be a causal one.

However, the argument that obesity studies are correlational is a misleading one. First, the body is complex: it is difficult to establish what are called “cause-and-effect” relationships between any two variables in the medical sciences. More important, not only is the body complex, but it is a complex system. This means that no single bodily event directly “causes” another bodily event. Weight increases cholesterol in the blood which accumulates and reduces blood flow, which increases stress on the heart which puts more stress on other bodily systems…and so forth. Obesity is part of a system of causes that together result in health problems.

And then, of course, the health problems themselves come to play a role in the further course of obesity and disease. If I am obese, I get winded more easily, which makes it more difficult to exercise, which leads to stop exercising, which leads to more weight gain, hopelessness about my capacity to lose weight, and so forth.

Whether direct “cause-and-effect” links have been established between obesity and health is not important. Obesity plays a central role in a system of “causes” that lead to health problems.

Is Weight Controllable? Fat acceptance advocates sometimes suggest that weight is not under an individual’s control. Is this true?

For many people, losing weight and keeping it off is difficult. It is correct that studies have shown that people who diet and lose weight often (but not always) gain all or most of their weight back once they stop dieting (Dulloo & Montani, 2015; Hall & Kahan, 2018) Studies suggest that environmental events – including the production of processed foods – can change taste receptivity and other biological changes that can lead to overeating (Harnischfeger & Dando, 2021; Lie et al., 2022; Pujol et al., 2021; Spinelli & Monteleone, 2021). Obese adults reported preference for fatty tasting foods as well as difficulty in inhibiting responses to fatty foods (Chmurzynska et al., 2021). Research suggests that people with obesity may have difficulty with executive control processes involved in inhibiting food responses.

Does all this mean that an individual’s weight is not controllable? No, it does not.

First, behavior matters. There are studies that suggest that the diets and exercise habits of people who are obese differ from those of people who are not obese (Moschonis & Takman, 2023). People with higher body weight tend to consume more soft drinks, more fast food, and fewer vegetables (Alsulami et al., 2023). They tend to engage in more overeating and binge eating (O’Neill et al., 2010). Overweight individuals tend to choose larger portion sizes and to eat more quickly (Labbe et al., 2017; Rodrigues et al. 2012; Rolls, 2018). Overweight children chose more higher calorie foods than non-overweight children in a role playing game (Snoek & Sessink, and Engels, 2010). People considered obese tend to engage in less moderate or high intensity exercise than people without obesity (Alsulami et al., 2023; Hall & Kahan, 2018).

Second, research has shown that lifestyle changes that promote weight loss are associated with long-term weight management. Lowe et al (2008) tracked a group of lifetime members of Weight Watchers, a group of largely female and middle-aged individuals who receive lifetime membership for maintaining their goal weight. The researchers showed that 80%, 71% and 50% of this sample were able to maintain their weight at or below their goal weight 1-, 3-, and 5- years after completing their programs. These are, of course, Weight Watcher’s most successful clients. The research nonetheless suggests that maintaining goal weight, although difficult, is not impossible.

Additional research shows people who change their mindset related to food and eating are much more likely to maintain desired body weight than those who do not (Veit et al., (2020). Just as weight gain changes food preferences and taste sensitivity, weight loss has the opposite effect; Andriessen et. al (2018) showed that weight loss decreases appetite and fosters changes in food preferences.

Third, the mere fact that average weight has changed over the years suggests that weight is something that can be influenced. There are many social changes that have occurred over the years that have led to general weight gain in the population. According to Komlos and Brabec (2010), these include:

While social and cultural changes may make it more difficult for individuals to manage a healthy weight, those same changes tell us what needs to be done individual, socially and culturally to modulate obesity. Personally, we can choose to take steps to change our attitudes toward consumption; to walk, take the stairs, and use the care less often; to seek out healthful foods. Socially, we can engage in physical activities with friends and put a limit on the time we sit and gaze into screens. Culturally, we can insist that the food industry produce real food rather than processed food, that industries stop trying to trap people into poor food choices; that municipalities build more walk- and bike-friendly cities

Isn’t this Fat Shaming?

And so, is being fat a bad thing? The answer? Not necessarily – but all things considered, it’s better for our health not to be obese.

But isn’t this fat shaming? Doesn’t saying that it’s not ordinarily good to be overweight demean people who are overweight?

I don’t think so. The “fat acceptance” movement is born of good intentions. It wants to preserve the dignity of people who are overweight. To do this, however, it seeks ways to not make people feel bad about themselves or about their weight. This, I think, is the wrong approach.

All people deserve dignity. No person deserves to be bullied or ridiculed because of their appearance. However, the key to preserving the dignity of people who are obese is to, well, not bully or ridicule them because of their weight. It is not to deny that being overweight is an issue. Being overweight can cause problems. We need to confront those problems – not deny that they exist.

The best way to confront personal problems is to first separate the person from the problem. To deal with a problem like weight, we have to first acknowledge that it is or can be a problem. We then should separate who we are as a person from the problem of being overweight. We should accept that this is a problem. And then we must cultivate the courage and resilience to have dignity as we confront the struggle with something difficult.

Obesity is a problem – not only for society but for individuals. But it is also possible — as Mark Twain intimated – to accept the fact of one’s weight, even lament it, but nonetheless choose the joys of eating over the struggle of weight management. There is no shame in that – as long as one knows what one is doing and why.

References

Chmurzynska, A., Mlodzik-Czyzewska, M. A., Malinowska, A. M., Radziejewska, A., Mikołajczyk-Stecyna, J., Bulczak, E., & Wiebe, D. J. (2021). Greater self-reported preference for fat taste and lower fat restraint are associated with more frequent intake of high-fat food. Appetite, 159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.105053

Dixon, J., B. (2010). The effect of obesity on health outcomes. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 316 (2), 104-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2009.07.008.

Dressler, H., & Smith, C. (2013). Food choice, eating behavior, and food liking differs between lean/normal and overweight/obese, low-income women. Appetite, 65, 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.01.013

Dulloo, A. G., & Montani, J-P. (2015). Pathways from dieting to weight regain, to obesity and to the metabolic syndrome: An overview. Obesity Review, 16, 1-6.

GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators (2015). Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years, New England Journal of Medicine, 377, 13-27. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614362

Hall, K. D., & Kahan, S. (2018) Maintenance of Lost Weight and Long-Term Management of Obesity. Medical Clinics of North America, 102, 1, 183-197. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.08.012.

Harnischfeger, F., & Dando, R. (2021). Obesity-induced taste dysfunction, and its implications for dietary intake. International Journal of Obesity, 45(8), 1644–1655. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-021-00855-w

Kasardo, A. E., & McHugh, M. C. (2015). From fat shaming to size acceptance: Challenging the medical management of fat women. In M. C. McHugh & J. C. Chrisler (Eds.), The wrong prescription for women: How medicine and media create a “need” for treatments, drugs, and surgery. (pp. 179–201). Praeger/ABC-CLIO.

Komlos, J. & Brabec, M. (2010). The evolution of BMI values of US adults: 1882-1986. Center for Economic Policy Research. https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/evolution-bmi-values-us-adults-1882-1986

Labbe, D., Rytz, A., Brunstrom, J. M., Forde, C. G., & Martin, N. (2017). Influence of BMI and dietary restraint on self-selected portions of prepared meals in US women. Appetite, 111, 203–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.11.004

Lam B. C. C., Lim, A. Y. L., Chan, S. L., Yum, M.P.S., Koh N.S.Y., & Finkelstein, E. A. (2023). The impact of obesity: a narrative review. Singapore Medical Journal, 64, 163-71.

Liu, X., Turel, O., Xiao, Z., He, J., & He, Q. (2022). Impulsivity and neural mechanisms that mediate preference for immediate food rewards in people with vs without excess weight. Appetite, 169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105798

Lowe, M. R., Kral, T. V., & Miller-Kovach, K. (2008) Weight-loss maintenance 1, 2 and 5 years after successful completion of a weight-loss programme. British Journal of Nutrition, 99, 4, 925-30. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507862416.

Mattes, R. (2014). Energy intake and obesity: Ingestive frequency outweighs portion size. Physiology & Behavior, 134, 110–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.11.012

McPhail. D., & Orsini, M. (2021). Fat acceptance as social justice. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 193(35), E1398-E1399. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.210772.

Mcwhorter, K. (2021). Obesity Acceptance: Body Positivity and Clinical Risk Factors. In Gaze, D. C., & Kibel, A. (Eds.) Cardiac Diseases – Novel Aspects of Cardiac Risk, Cardiorenal Pathology and Cardiac Interventions. IntechOpen. Doi: 10.5772/intechopen.93540

Moschonis G., & Trakman, G. L., (2023). Overweight and Obesity: The Interplay of Eating Habits and Physical Activity. Nutrients, 15(13), 2896. doi: 10.3390/nu15132896.

Pujol, J., Blanco-Hinojo, L., Martínez-Vilavella, G., Deus, J., Pérez-Sola, V., & Sunyer, J. (2021). Dysfunctional brain reward system in child obesity. Cerebral Cortex, 31(9), 4376–4385. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhab092

Reilly, J. J., Methven, E., McDowell, Z. C., Hacking, B., Alexander, D., Stwart, L, and Kelnar, C. J. H. (2003). Health consequences of obesity. Archives of Diseases in Childhood, 88, 745-752.

Rodrigues, A. G. M., da Costa Proença, R. P., Calvo, M. C. M., & Fiates, G. M. R. (2012). Overweight/obesity is associated with food choices related to rice and beans, colors of salads, and portion size among consumers at a restaurant serving buffet-by-weight in Brazil. Appetite, 59(2), 305–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.05.018

Rolls, B. J. (2018). The role of portion size, energy density, and variety in obesity and weight management. In T. A. Wadden & G. A. Bray (Eds.), Handbook of obesity treatment., 2nd ed. (pp. 93–104). The Guilford Press.Sol-Smith, V. (2023). Fat talk: Parenting in the age of diet culture. Holt.

Veit, R., Horstman, L. I., Hege, M. A., Heni, M., Rogers, P. J., Brunstrom, J. M., Fritsche, A., Preissl, H., & Kullmann, S. (2020). Health, pleasure, and fullness: Changing mindset affects brain responses and portion size selection in adults with overweight and obesity. International Journal of Obesity, 44(2), 428–437. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-019-0400-6

If you like what we are doing, please support us in any way that you can.