Michael F. Mascolo, Ph.D.

Recently, arguments have emerged in opposition to the practice of “cultural appropriation”. Oxford Languages defines cultural appropriation as:

the unacknowledged or inappropriate adoption of the customs, practices, ideas, etc. of one people or society by members of another and typically more dominant people or society: “His dreadlocks were widely criticized as another example of cultural appropriation.”

Drawing on the example provided by Oxford Languages, wearing dreadlocks can be seen as an act of cultural appropriation because a person:

Some have suggested that cultural appropriation is an inherently oppressive practice. Objections to cultural appropriation have their origins in the noble desire to foster equality and respect among social groups and to remove systems of institutionalized power that oppress traditionally marginalized groups. When one group – particularly a more dominant group – adopts customs, practices and ideas from the culture of a less dominant group, it uses the less dominant group for its own purposes, and perpetuates an institutionalized system of inequality. The antidote to oppression through cultural appropriation is for dominant cultures to “stay in their own lane” – to respect the boundaries that separate one cultural group from another.

The goal of empowering marginalized social groups is of central importance. It is not clear, however, that calls to eliminate cultural appropriation will advance that cause. There are many reasons why this is so. First, the appropriation of culture is an inevitable part of the process by which individuals and cultures develop. As people from different cultures interact, they routinely adopt and incorporate practices from one another. This basic historical process occurs in both peaceful and exploitative ways. In this way, it is not cultural appropriation that is problematic, but instead acts of exploitation. They key is to promote ways of intercultural engagement that foster mutual enhancement rather than exploitation.

Second, objections to cultural appropriation are based upon an erroneous conception of culture. Cultural appropriation can be inherently bad only if we think of different social groups as quasi-sovereign entities – separate and distinct entities that somehow “own” the practices with which they identify. But cultures are not sovereign entities. They are not the kinds of things that can claim “ownership” over their practices. Cultures are shared and contested systems of beliefs, values and practices. They are shared ways solving personal and social problems. They are resources to be used, not possessions to be owned. In what follows, I contrast open and closed conceptions of culture.

I argue that objections to cultural appropriation are based on a flawed model of culture – namely the idea that cultures are quasi-sovereign systems that are closed off from one another. From this view, when we argue against cultural appropriation, we are making an argument to keep cultures separate (i.e., “stay in your own lane”). However, cultures are not closed systems. They are open-ended, dynamic systems that are continuously mixing and moving. Thinking of cultures as open systems changes how we view the issue of cultural appropriation. Cultural appropriation – a form of cultural exchange — becomes an integral part of the development of culture. Problem in intergroup relations do not arise from cultural appropriation per se, but from specific acts of disrespect, misrepresentation and exploitation. It is better to foster the empowerment of marginalized groups through mutual transformation than by separation.

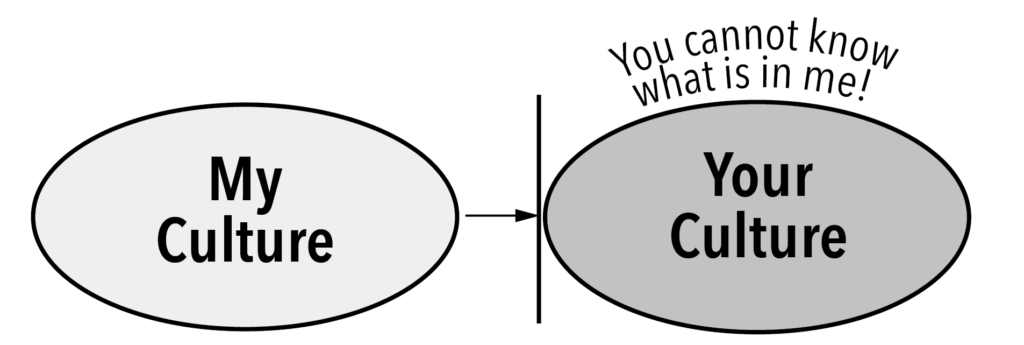

There are at least two contrasting conceptions of culture that are relevant to the discussion of cultural appropriation. We tend to think of cultures as “closed systems” – separate and distinct sets of beliefs and practices that distinguish one culture from another. This is shown in Figure 1:

In this view, cultures are:

When we adopt this view of culture, we imagine that each culture is defined by a separate set of beliefs and practices that make them what they are. When we do this, other cultures or groups often appear “strange” to us. Since they are “other”, we assume that they are in some way fundamentally different, unknowable, or impenetrable. We tend to think of “our culture” as “ours” and “their culture” as theirs. If our culture is “ours”, then we “own” the practices that make it up; if their culture is “theirs”, then they “own” their culture’s practices. Viewing culture in this way, cultural appropriation occurs when an outsider trespasses on another culture’s boundaries.

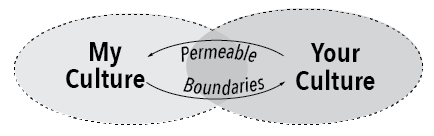

If any of these beliefs about culture do not hold, then moral objections to the practice of cultural appropriation begin to lose their force. In fact, none of these everyday conditions describe what it means to be a culture. Cultures are dynamic, open systems that continuously evolve as they respond to novel challenges. The open view of culture is shown in Figure 2:

From this view, cultures are:

In what follows, I will describe how objections to cultural appropriation tend to build upon the closed model of culture. In so doing, I want to show that much of the rhetorical force behind objections to cultural appropriation rely upon the closed conception. I will argue that because the assumptions of the closed model are incorrect, typical objections to cultural appropriation are based on a series of false premises.

The assertion that cultural appropriation is fundamentally wrong ignores the fact that appropriating from other cultures is one of the most basic ways that cultures develop. It is so ubiquitous that we hardly notice it. As open systems, cultures evolve, in part, by adopting, incorporating and transforming traditions, practices and artifacts from other cultures. Here are some examples:

Cultures change and develop as they encounter novel values, meanings, practices and artifacts that have their origins outside of the self. However, the appropriation is not always benign. It just as often comes from the conquest of one nation or culture by another. History is replete with examples of appropriation, exploitation and theft through conquest. Indeed, the primary reason for conquest is the assumption that conquest pays (Liberman, 1993). There are countless examples:

Cultural appropriation itself is not inherently bad; problems in intercultural exchange arise from specific acts of disrespect, exploitation and theft.

If we think of cultures and identity groups as self-contained and sovereign systems, to appropriate a practice from another culture is to trespass on its boundaries. From this point of view, marginalized cultures are harmed when a dominant culture appropriates from a less dominant culture. Such harms occur when a dominant culture (a) misrepresents a less dominant cultural group for its own purposes; (b) misuses or mocks the beliefs, practices or artifacts of a less dominant cultural group, or (c) steals or takes credit for artifacts or other forms of goods produced by socially marginalized cultures.

Misrepresentation is said to occur when member of a dominant culture promulgates incorrect, pejorative or stereotypical depictions of minority groups (Kalyan, 2021; Said, 1979). Critics have cited a variety of examples. These include

These acts can be viewed as a practice that might be called “outgroup representation” – the attempt to describing, characterizing or representing the experiences of one socio-cultural group by members of another. To be sure, such practices can be risky. When a member of one cultural group seeks to understand the experiences of another, they inevitably do so through the lens of their own values and beliefs. This is a risk that outgroup representations may distort or devalue cultural practices that depart from the values of the observer. Further, because of differentials in credibility, status or social power, members of marginalized social groups cannot always correct accounts made by outsiders. When this happens, the characterizing voice of the more powerful party tends to predominate over the less powerful party. Still further, because outsiders are not typically privy to the knowledge and experience of cultural insiders, the risk of misrepresentation can be high.

Thus, critics of “outgroup representation” suggest that it is often unacceptable for outsiders to seek to represent the collective experiences of insiders. However, this conclusion holds only if we adopt a closed conception of culture. In the closed model, cultures are separated from each other by rigid boundaries. Because it is assumed that our cultures are “closed off” from each another, I can’t “see into” your culture, and you “can’t see” into mine. Only I can have access to my culture’s meanings, practices and values. And if that is true, then you can never really be said to “know” my culture.

We hear versions of this sentiment when people say, “You are not me! You can’t know my experience! Only I can know my experience!” But this is simply not true. As both individuals and cultures, we are never entirely “closed off” from one another. Although your culture may be distinct from mine, we are nonetheless capable sharing experience with each other.

(For example, newborn infants imitate the facial actions of adults. If an adult sticks out her tongue, the infant often follows suit. This is possible because the sight of the adult’s facial expression activates behaviors and states in the infant that are similar to those expressed by the adult. Studies suggest that infants are capable of primitive forms of empathy, shared experience with others, mimicry, and other ways of engaging others. We do not enter life isolated from each other; we have the capacity to connect from the start.)

Further, in many circumstances, social outsiders can gain access to cultural practices and experiences that are largely inaccessible to insiders. Outsiders are not the only ones with biases: insiders have them as well. Like outsiders, insiders view their own experiences through their own ideological beliefs and values – perspectives about which they are often unaware. As a result, outsiders who interact with insiders are often able to identify biases and beliefs that insiders take for granted. As a result, outsiders often have insights into insider experiences to which insiders themselves may be blind. Indeed, if this were not the case, it would not be possible for one group to identify biases in another.

The capacity to share experience is what allows, for example, Daryl Davis – a Black soul singer – to understand, befriend and even transform the beliefs of members of the Ku Klux Klan. It allows Daniel Day Lewis to vividly interpret the role of a disabled man in My Left Foot, or for audiences to appreciate Morgan Freeman in the role of “Red” in Shawshank Redemption – a Irish character named for his red hair. It is what underlies the capacity for a white male, Anton Chekov, to compose a novel – A Doll’s House – that is seen by many as a faithful representation – often characterized as presciently feminist — of the experience of many Western women.

Misuse is said to occur when a dominant culture adopts stories, motifs, practices, meanings and artifacts for its own advantage from less dominant cultures or social groups, and/or without acknowledging the origins and significance of those practices the cultures in which they originated. Critics have identified a variety of events as characterizing misuse of cultural practices and motifs:

The idea that use or “misuse” makes sense only if we believe that there is a single or “proper” way to “use” a given practice, or that the practice in question is somehow the “property” of a particular culture. There are two senses in which we can think of any given cultural practice as one’s “own”. The first involves an act of identification: “this practice is part of my culture; it is part of what makes me me.” In this sense, the cultural practice is “my own” in the sense that it is an expression of my identity. The second sense involves the concept of ownership or possession. Even though a cultural practice may be said to be “one’s own”, cultures do not “own” the practices they create or use. Unlike persons, families, organizations or nations, cultures are simply not the kinds of entities that care capable of “owning” something.

Second, cultures are not distinct or homogeneous systems. Cultural practices and traditions evolve over time. Similar practices can evolve independently in diverse cultures. For example, dreadlocks are not exclusive to African or African-American groups. Dreadlocks have been worn in ancient and modern African, Egyptian, Hindu, Greek, Roman, Rastafarian and other cultures.

In this way, no single culture can claim dreadlocks as an exclusive part of its identity. Similarly, there are few practices, if any, that are common to all members of any given culture. Not all members of any given culture wear dreadlocks or engage in any other particular practice. In this way, cultures are heterogeneous rather than homogeneous. No single cultural practice separates cultural insiders from outsiders.

A culture is a system of meanings, values and practices. The practices of any given culture reflect the shared and contested ways that any given social group has come to solve the perennial problem of group adaptation. The products of culture are not things to be owned, but instead practices to be used. If cultures do not own their practices, no single practice is shared by members of any single group, and similar practices are shared by members of diverse cultural groups, it becomes difficult to justify the claim that the use of practices from one culture to another – even from a more dominant culture – is not in itself problematic.

The concept of “theft” overlaps with “misuse”. In both concepts, individuals from one culture are understood as illegitimately claiming possession of something from another culture. The clearest cases of theft occur when one culture takes into its possession artifacts from less dominant culture. Examples include:

Perhaps the most salient examples of cultural theft involve examples in which museums hold artifacts obtained through the conquest of other nations and cultures. There is something morally unsettling about the idea of a museum curating taken from other cultures for the pleasure of non-indigenous viewers. The experience is even more repugnant when museums display such artistry in institutions of natural history rather than in museums of art. Such a practice casts the works in question as a representation of something exotic or alien – as something not worthy of being depicted as a fully human artistic creation.

Even in cases that might can clearly be regarded as theft, difficult issues emerge. What does it mean to say that a work of art should be returned to its culture of origin? Who or what owns the work of art? For example, Frum has described how, in the late 20th century, a large cache of art (the Benin Bronzes) were taken from Benin’s (now Southern Nigeria) oba (King) by British soldiers. To this day, over 3000 are distributed amongst a variety of Western museums and private collections. Most would agree that the securing of these items should be regarded as an act of theft. The objects should be returned to their rightful owners – regardless of the circuity of the route by which they landed in public or private hands.

However, what does it mean to say that artwork should be returned to its culture of origin? Who “owns” this artwork? The current government in Benin in planning to build a public museum to house the Bronzes. However, the current oba of Benin – the great grandson of the oba from whom the bronzes were taken – has argued that the bronzes are the personal property of his family. The oba – while deeply revered as a religious figure – has little political power. However, the people of Benin broadly view the government – who is planning to erect the museum — to have a history of corruption. There is a question of the safety and security of these treasures. Who is the proper owner of the bronzes?

The point here is not to answer the question; instead, it is to illustrate the instability of the concept of culture even in cases many would agree clearly involve theft. A culture is not a nation or a person; a culture is a system of beliefs, values, practices and artifacts. One can steal from a person, an organization or even a nation. To speak of stealing from a culture is to speak metaphorically. Yet much hangs on the use of this metaphor in current political discourse.

Calls to end cultural appropriation are but one of the tools that progressivist thinkers use to protect marginalized groups from intrusions of dominant groups. However, this approach privileges diversity over unity. When we treat social groups as separate and distinct entities, we risk polarization and social fragmentation. The agendas of each group are pitted against the other. Managing conflict becomes a matter of keeping cultures separate rather than of coordinating differences. In this way, we need ways to achieve unity within diversity.

In the open model of culture, cultures have permeable boundaries. They exist in relation to each other and develop through intercultural exchange. Within this approach, cultural appropriation is not an inherent threat. Problems arise between cultures not from appropriation itself, but from acts of misrepresentation, exploitation, and theft. Thus, instead of seeking blanket prohibitions against “cultural appropriation”, it is better to identity and seek to mitigate misrepresentation, exploitation and theft.

Let us examine this issue in relation to a thoughtful critique about cultural appropriation by a yoga practitioner:

Yoga is estimated to be at least 2,500 years old, originating in the Indus Valley Civilization. But if you google “yoga”, check out yoga magazine covers, or scroll through yoga-related hashtags, you often won’t see an Indian person. Much of the time, you’ll see white, fit, flexible women practicing postures—the more physically demanding, the better—in expensive stretch pants on beaches or in chic workout studios.

According to yoga Sutras (classic texts), yoga asana [yoga postures] is just one of yoga’s eight limbs. Unfortunately, it has now been glorified to the point that the very definition of yoga has been usurped. The yoga I knew from my Indian upbringing—the spiritual philosophy embedded in everyday experiences—is no longer seen as yoga. Practices in the other limbs of yoga—such as purification of body, mind, and speech, controlling human impulses, the practice of breathing to control the life force within, supporting collective humanity, and mental exercises through meditation—are often cast aside or forgotten in many forms of modern practice (Deshpande, 2017).

Deshpande laments the fact that American yoga bearsFeuerstein, G. (2008). The Yoga Tradition: Its History, Literature, Philosophy and Practice. Prescott, Arizona: Hohm Press. little similarity to yogic practices as they have traditionally been practiced in India. She is correct: Indian yogic practices are more spiritual, religious, structured and hierarchical than their American counterparts [8]. The core principles of yogic practice are all but missing in typical American practices.

American practitioners of yoga have every right to import and adapt yoga practices as they see fit. No culture or religion owns the symbols or traditions that make it up. American practitioners have no obligation to honor any of the traditions of Indian spirituality or culture in their practices. Because cultures always transform the practices that they appropriate to fit their own needs and traditions, we should not be surprised to find that American practitioners have adapted yogic practices to American culture.

Problems arise when American practitioners claim to be promoting or even adapting Indian traditions. When this occurs, issues of misrepresentation, misuse and theft begin to emerge. If I claim to act in the name of a particular tradition, I have essentially identified myself with that tradition. As a result, I become obligated to represent those traditions as faithfully as I can, to engage in practices that honor the traditions in question, and to acknowledge the origins and history of the traditions I espouse.

Of course, the process need not be all or none. I am free to adapt the traditions of the other. However, to the extent that I identify aspects of my practices with a particular tradition, I become obligated to identify how those traditions inform the practices I create. It is also possible to reject and even critique certain beliefs practices of another culture as I appropriate and transform them to my own. For example, an American practitioner is free to reject the hierarchical structure of traditional Indian yogi-student relations in favor of more egalitarian relationships. Even in rejecting such practices, it is best to act with care, compassion and respect for the other – even in the face of disagreement.

Charges of cultural appropriation tend to gloss over important distinctions. In so doing, they act as a kind of rhetorical bludgeon. The accused is expected to stand down or else face charges racism, bigotry or ethnocentrism. This strategy ultimately seeks to empower marginalized groups by sharpening cultural differences rather than by building shared ways of being. But cultural appropriation is not the culprit. The culprits are exploitation and cultural superiority.

Elkins, C. (2022). Legacy of violence: A history of the British empire. Knopf.

Feuerstein, G. (2008). The yoga tradition: Its history, literature, philosophy and practice. Prescott, Arizona: Hohm Press.

Kalyan, A. (2021). “Cultural Misrepresentation of the East in Nicholas Roerich’s Art.” Inquiries Journal, 13(02).

Liberman, P. (1993). The spoils of conquest. International Security, 18, 125-153.

Said, E. V. (1979). Orientalism. Knopf Doubleday.

White, R., & Francis, S. (2016). A culture shaped by immigrants: Examining the consequences of U.S. Immigration policy. International migration: Politics, policies and practices (pp. 1-45). Nova.

If you like what we are doing, please support us in any way that you can.