Michael F. Mascolo, Ph.D.

Sex doesn’t trump gender; but gender doesn’t trump sex either.

Traditionally, the contrast between “male” and “female” has been one of our most foundational social distinctions. The question of transgenderism calls this traditional distinction into question. A transgender individual is one whose gender identity is discordant with their biological sex. Transgenderism raises difficult questions. What criteria do we use to identify a person as male or female, boy or girl, man or woman? Biological sex? Self-identification? Who gets to decide? What makes a man a man and a woman a woman? Is a transman a man? Is a transwoman a woman?

People differ on this issue. Some privilege sex over gender. Let’s call these people naturalists. For naturalists, there is only sex — “gender” is a mere creation. For naturalists, men are men and women are women; those who claim a gender that deviates from their sex are simply delusional. Naturalists tend to believe that humans are born with an inherent nature – male or female – and that there is nothing that can be done to change it.

Others privilege gender over sex. People who do so tend to rely upon the idea that “gender is socially constructed”. Social constructionism is a way of understanding the origins of our concepts. For social constructionists, words – like “male”, “female”, “man” and “woman” — are not so much “mirrors of nature” as much as they are social categories that allow us to interpret the world in different ways. As a result, words do not so much carve “nature at its joints” as much as they are social interpretations that could have been made otherwise.

Transcending Transgender Divides

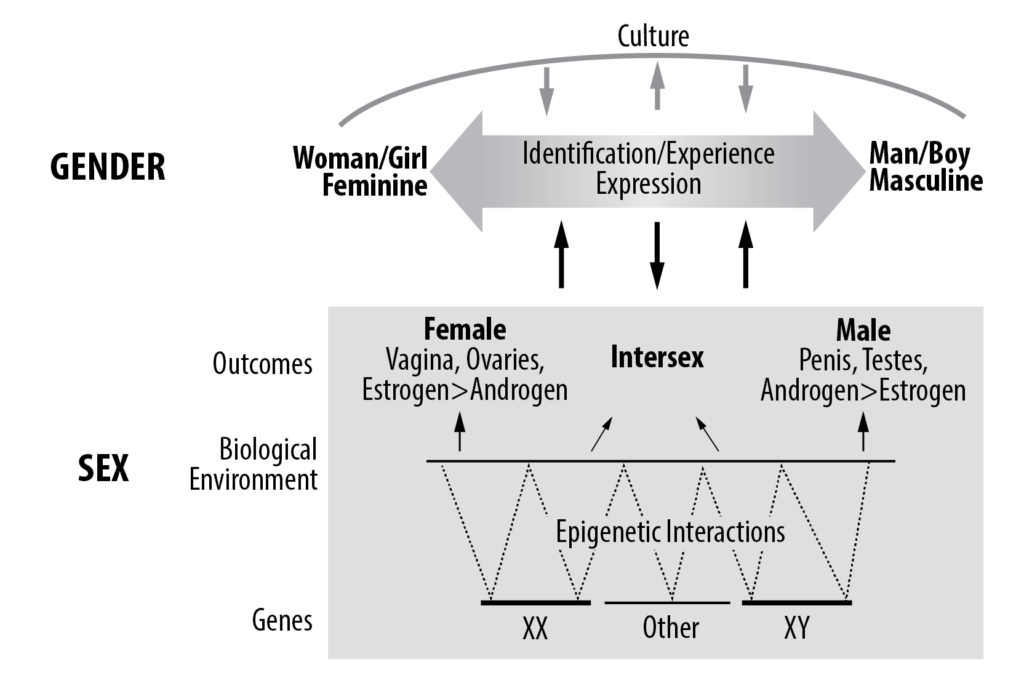

I suggest that there are ways to reconcile the naturalist and social constructionist positions. We begin with the assertion that the distinction between sex and gender is a useful one. Sex is a biological concept defined in terms differences between people in their reproductive anatomy. It is based upon the public capacity to identify person’s chromosomal structure and reproductive anatomy. In contrast, gender identity is a form of experience. It refers to a person’s deep-seated sense of being a boy or girl, man or woman, or something else. The determination of gender identity is a socio-psychological process. It occurs as individuals assess the relations between their experiences of self and the socially-shared categories that define what it means to be a male or female, boy or girl, man or woman.

If this is so, it follows that a person is defined in terms of both their biological sex and their gender identity. A cis-gendered person is one whose gender identity is concordant with their biological identification. More difficult questions arise when we consider the case of transgenderism. How are we to identify the “sex/gender” of such persons?[1] By their biological sex? By their self-identification? Either answer raises problems. If we identify a person in terms of their sex, we fail to acknowledge the person’s gender identity as a source of personhood. In contrast, if we identify the person in terms of gender identity, we fail to acknowledge their biological status as an aspect of their personhood. Either way, the traditional definition of “man” or “woman” fails to capture the complexity of transgender personhood[2].

Happily, we already have terms that identify the gender of transgender individuals. These include terms such as transman, transwoman, transqueer, genderfluid, nonbinary, and so forth. Such terms identify what it means to be transgender from both the first- and third-person point of view. That is, from the first-person perspective, they affirm the transgender person’s chosen gender; from the third-person perspective of society, they acknowledge the existence of sex-based physical anatomy.

This line of thinking maintains the distinction between “trans-man” and “man” and between “trans-woman” and “woman”. Assertions like “A ‘trans-woman’ is a ‘woman’” are meant to affirm transgender personhood while affording the transgender individual the full range of the benefits enjoyed by his or her chosen gender. Despite this noble goal, such assertions simply fail to acknowledge the biological and socio-historical differences between persons who transitioned from one gender to another and those who did not. The desire to assert an equivalence between “trans-man” and “man” likely comes from the sense that society places differential value on these identities. One might suggest that the solution to this problem, however, is not to assert a false equivalence, but instead to work toward honoring transgender identities as valued and valid ways of being human.

To bridge divides in the transgender debate, we must deal honestly with the contradiction between sex and gender. In what follows, I first make the case for the “reality” of biological sex as a stable but open-ended aspect of social personhood. I then make the case for the “reality” of gender identity, with a focus on transgender experience. I then explore the relationship between the concepts of sex and gender. I argue that while sex and gender are distinct concepts, they are not independent of each other. From this point of view, one way to seek a resolution to the transgender wars is to embrace and honor the complexity of transgender personhood without denying the reality or importance of either gender or sex.

The Realities of Biological Sex

Let’s’ unpack these arguments a bit. Let’s start with the concept of sex.

Traditionally, we have tended to think that there are two sexes: males and females. Males and females are born with different forms of sexual anatomy that serve different reproductive functions. Males are born with XY chromosomes, testes and a penis; females are born with XX chromosomes, ovaries and a vagina. At puberty, males and females develop secondary sexual characteristics. Boys grow stronger; their voice lowers, their testicles descend. Girls begin to menstruate, develop breasts, and become capable of bearing children.

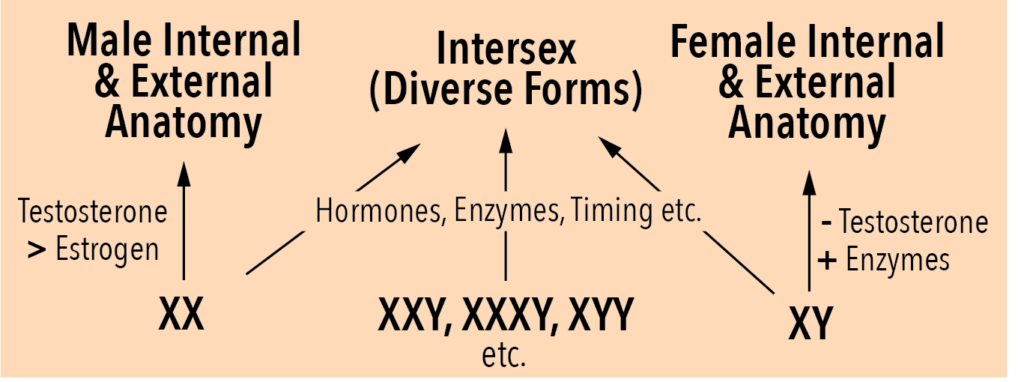

For most humans, the biological distinction between male and female works quite well. However, while most people fall into the biological categories of male and female, not all do. Intersex individuals are born with atypical patterns of internal and/or external reproductive anatomy. For example, XX fetuses that are exposed to androgens (male sex hormones) early in development often develop internal and/or external male genitalia. If an XY fetus lacks the capacity to produce a particular protein, it can develop both male and female genitalia.

Differences in a fetus’ genes (e.g., XXY, XXXY, XYY, and others) can also result in atypical forms of sexual anatomy. For example, individuals born with Klinefelter syndrome (XXY) develop smaller testicles and produce less testosterone. This produces reduced muscularity, enlarged breast tissue, and less body and facial hair.

Note that being intersex is not the same as being transgender. Based on a suite of criteria, most people who are intersex are assigned a sex (male or female) at birth. While some intersex individuals undoubtedly change genders over time, most intersex individuals are content with their sexual assignments. It is likely that there are more intersex individuals than there are persons who identify as transgender. Estimates of the proportion of persons who are intersex range from .03 to 1.7 percent of the population. The proportion of individuals who identify as transgender is approximately .06 percent.

Does this mean that sex a social construction? So, there are multiple outcomes in the development of sexual anatomy. Does that mean sex a social construction? Well, it depends on the meaning of “social construction”. Like all concepts, the concept of sex is a product of how human beings interact together to make sense out of the world. Most people are born with either male or female sexual anatomy. It would thus make sense that, over human history, people would spontaneously come to believe that there are two sexes. We see now that the situation as more complex. It follows that our previous shared and accepted ways of understanding sex were inadequate. This calls for people to create new categories – namely the varieties of intersex classifications. In this way, we can say that the concept of sex is a social construction.

However, if by “social construction”, we mean that “biological sex” is an arbitrary product of social interpretation, then “sex” is no mere social construction. To be sure, the concept intersexuality is a product people working together and agreeing upon a way to understand some aspect of the word. That doesn’t mean that intersexuality is an arbitrary social invention; it is based on careful research and stable patterns of evidence. So, although we create social categories to interpret our worlds, we can’t interpret the world just any way that we want. The world is recalcitrant – it fights back; it resists our social constructions. The fact that there are multiple outcomes in the development of sexual anatomy doesn’t mean that sex is a social construction. It simply means that there are multiple forms of biological sex.

The Realities of Transgender Experience

While sex is a biological concept, gender is a social or psychological concept. While sex is defined in terms of differences in reproductive anatomy, gender identity is a form of experience. It is a result of how people experience themselves and identify themselves as gendered beings. To have a gender identity is to identify oneself in terms of the social categories that define what it means to be male or female boy or girl, man or woman.

Biological sex is real. However, transgender experiences are also real. That they are social rather than biological phenomena does not make them less real. The most compelling examples of transgender experience come from early onset transgender experience. This occurs when children insists upon gender identities that are contrary to their biological sex at early ages — despite overwhelming pressure by parents and society to the contrary. The following comments are typical reflections of what it was like to be a transgender child:

Since my kindergarten years, I learned that I was different from others. When I was in the neighborhood with my boyfriends and they played boy games like football, I would step down and go to girls and play with them. I was always the mommy in games. I always had a doll, but my parents did not buy it. I was saving my money to buy one (Afrasiabi & Junbakhsh, 2018, p. 1870).

I knew that I was biologically a girl, but ever since I was little, I always wanted to be a man so bad. Other people said I want to be a lawyer, a doctor, and I said I want to be a man (Grossman & Auguelli, 2006, p. 121)

Since I can remember, I always thought I was a girl. I used to do things as a girl, sit on the toilet. I wouldn’t stand up. I never liked using urinals. I never liked boy things. I didn’t like boys’ stuff, I always liked girls’ stuff (Grossman & Auguelli, 2006, p. 121):

The experiences of being a transgender adult are varied and broad reaching. Although they are often organized around deep-seated sense that one is not at home with one’s body, the experience tends to be is «more profound. There is often a desire to be seen and experienced by others as a genuine member of their chosen gender. The sense of being able to relate and connect to others in terms of one’s conception and experience of one’s chosen gender is important:

So yeah. I went out, and I felt this strange feeling, and the comments from straight guys – imagine! It was so good Like, oh, my god! I just can’t find the words to describe it, like, I’m in heaven, you know? Like, “Yes! That’s what I wanted!” Just the feeling of presenting me outside. Not like walking in this jail. I call my male body “jail”. And also, I want to try hard. I hope so, to keep my figure, so it’s like it feels good, like it raises my self-esteem when people say, like, “Wow! You look good as a girl.” And then I say, “I worked hard to be that way” (Budge, 2013, pp. 142-143)

As a result, there is a deep sense that one is most authentic as a member one’s chosen gender.

It was just like a little light bulb had gone ping! Suddenly my clouded head of, “Oh, you don’t know what you are”…and it was nice just to find out who I was instead of drifting around not really understanding (Boddington, 2016, p. 37).

I feel very free being trans. I mean, being, finally living as my true self, from everybody that‘s in my life, them knowing me as this person, not have to hide and pretend that I’m this other person. And that’s kind of how I always felt growing up – trying to pretend. (Budge, 2013, 136).

These descriptions of transgender experience are merely the tip of the iceberg. There are may ways of experiencing the self as transgender. What is most interesting about these experiences is that they tend to occur despite strong opposition by parents, teachers, peers, and society in general. Although many suggest that the existence of transgender identities suggest that gender is a social construction, the idea that people adopt transgender identities despite social pressure to the contrary is inconsistent with this view. At the very least, such findings suggest that transgender identities are not the result of “socialization.”

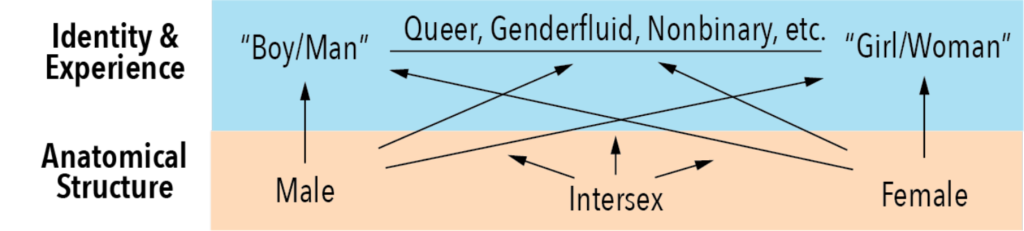

There are many ways to be transgender. And there are many pathways in the development of transgender identities. As shown in Figure 2, different forms of transgender identity can develop in individuals regardless of their biological sex.

So, does this mean that sex and gender have nothing to do with each other? Some believe that because sex and gender are different, they have nothing to do with each other. In so doing, they make the mistake of believing that sex is biologically determined but gender is socially determined. For example, Henderson (1984) states, “The meaning of gender is constructed by society, and each of us is socialized into that construction. Thus, gender is a set of socially constructed relationships which are produced and reproduced through people’s actions” (p. 121).

So far, so good. It is true that the meaning of gender is constructed by society. However, the meanings that societies make of gender are also influenced by biology.

For example, the most obvious difference between biological males and females is that females can give birth, can breastfeed children, and menstruate; men cannot. As a group, adult males are larger, stronger and faster than females. These biological differences influence the social organization of all societies. To be sure, cultural groups differ in the ways in which they respond to these differences. For example, because they are constantly moving, the division of labor within hunter-gatherer groups tends to be more egalitarian than in agricultural societies. When people began to settle in one place and plant their food, divisions of labor emerged. Biological differences between men and women motivated different roles: women were more likely to attend to childrearing; the use of the plough required the type of upper body strength typical of adult men. Today, novel technologies (birth control, bottle feeding, etc.), beliefs (e.g., equality, feminism) and practices (e.g., pressures on men to care for children; access to abortion) facilitate greater gender equality.

To be sure – the meaning of gender is socially constructed. However, social construction is not independent of biology. Biology influences the ways in which gender is constructed in any given society. Biology and culture influence each other; they are inseparable in the social construction of gender. If this is so, we must take biology into account when we are talking about the construction of gender identity.

It is obvious that, as a group, sex differences in size, strength and reproductive capacities exist. However, this is merely the most basic way in which males and females differ. Evidence suggesting that biological differences between males and females influences psychological development is simply overwhelming. This does not mean that gender is “biologically determined”; cultural expectations and socialization play a profound role in the development of gender. What it does mean is biology and culture are inseparable as causal factors in the development of gender in both individuals and societies.

There is also growing evidence that biology plays a role in the development of transgender identities. Researcher have shown the identical twins are more likely to develop transgender identities than fraternal twins or ordinary siblings. This suggests that differences between people in their genes are associated with differences in gender identity (i.e., cis- or transgender). Other researchers have reported that certain brain structures in transgender individuals are more similar to those that are typical of their self-identified gender than their biological sex. While these studies are in their infancy, they suggest that a role for biological predispositions in the development of gender identity (i.e., cis- versus transgender).

Let’s put these ideas together. Given all of the above, we can draw several conclusions.

The desire to regard “gender” as a form of self-identification has noble roots. Historically, society has not had a place for transgender persons. It has discriminated against them and denied the legitimacy of their experiences. It has prevented them from living authentic lives – lives that comport with their sense of who they really are. When this happens, it is essential to rise up and demand changes in one’s oppressive conditions.

Toward this end, the concept of self-identification has rhetorical force. We are an individualist nation. We believe in freedom of choice and the right of self-determination. From this view, the idea that gender is a matter of self-identification has great moral and rhetorical force. In a nation that values freedom of the individual, what greater freedom could there be than to identify oneself as one sees fit?

However, our desire for self-determination notwithstanding, there are deep problems with the idea that gender is a mere matter of self-identification. Embracing this concept would fundamentally alters the meaning of terms like “male”, “female”, “boy”, “girl”, “man” and “woman”. It means shifting their criteria for defining these terms from the biological to the psychological sphere. When this happens, a biological female who identifies as a man must be considered a “man”. A biological male who identifies as a woman must be considered a “woman”. Biological sex becomes irrelevant.

The problem is that biological sex is not always irrelevant. As social, self-aware beings, we are, in part, who we think we are. However, we are not only who we think we are. We are psychological beings, but not only psychological beings. We are also biological beings. We are biological organisms. We have bodies that have physical attributes. Thus, while gender can be defined with reference to personal and social experience, biological sex cannot. Instead, sex is defined in terms of chromosomes, internal and external reproductive anatomy, secondary sex characteristics, and so forth. These structures exist independent of how we experience them. As physical structures, they are open to the observations of others. Thus, while our bodies may be our own, they are not simply objects for us; they are objects for others as well. As a result, they are not socially neutral; they have implications for other people.

In other words, if is helpful to discriminate between sex and gender, then it is not appropriate to gloss over the distinction, privilege one quality over the other, or to assimilate one to the other. That is, it is not appropriate to use “gender” when we mean “sex” (and vice versa); to suggest that gender or sex is de facto more important than the other, or to suggest that one category subsumes or incorporates the other (e.g., that gender identity erases the significance of sex).

Although sex and gender are distinct, one does not necessarily trump the other. Instead, sex and gender operate in different spheres of social life. If this is so, then society’s job becomes one of

(a) honoring the dignity of transgender persons, (b) embracing transgender persons without denying either sex or gender as aspects of social personhood, and (c) identifying when sex and gender matter in social life, and when they do not.

There are many social contexts in which transgender identity should be irrelevant. Transgender individuals should not be discriminated against in employment, housing, healthcare or in any other right or benefit that society has to offer. It should not matter whether our politicians, clergypersons, or teachers are transgender. Transgender individuals should be referred to using their preferred pronouns. Transgender people should be welcomed without prejudice into all realms of social life.

However, there are places where the biology of transgender individuals matters in social life. Perhaps the best example of this issue involves the issue of transgender athletes. Recently, there has been much attention to the issue of whether transgender women have an unfair advantage over cisgender women when they complete in women’s sports. In 2015, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) decided that transgender woman are eligible to compete in women’s competitions provided that their testosterone levels are suppressed for at least 12 months prior to competing. The question becomes whether transwomen whose testosterone is suppressed in this manner retain an advantage of their cisgender opponents. The limited research that exists strongly suggests that they do. Research suggests modest changes (5%) in muscle mass and strength over the course of treatment. Other research suggests that athletic performance in transwomen does not decline significantly after the course of testosterone suppression. Such studies suggest that the male advantage in athletic competitions is sustained after male to female transition in transwomen.

In most social contexts, the question of transgender social identities should simply be irrelevant. However, there are contexts in which the biological sex of transgender individuals matter. The inclusion of transwomen in women’s athletics is one such area. It should not matter to swimmers whether a person identifies socially with one or another gender. However, it would be an error to assume that social identity erases the significance of biology.

Afrasiabi, H., & Junbakhsh, M. (2019). Meanings and Experiences of Being Transgender: A Qualitative Study among Transgender Youth. The Qualitative Report, 24(8), 1866-1876. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2019.3594

Harper J. (2015). Race Times for Transgender Athletes. Journal of Sporting Cultures and Identities, 6, 1-9.

Pitsiladis, Y., Harper, J. et. al., (2016) Beyond Fairness: The Biology of Inclusion for Transgender and Intersex Athletes, Current Sports Medicine Reports, 15, 386-388

[1] The very conception of transgender identities relies upon the distinction between sex and gender. However, the terms “sex” and “gender” are often used interchangeably. No doubt, this practice is often the result of mere confusion. However, glossing over the distinction between sex and gender can be used as a strategy, conscious or unconscious, to define one concept in terms of the other – that is, to imply that sex is defined by gender, or vice-versa. If we are to maintain the distinction between sex and gender, it becomes important to carry it forward in everyday discussion. I will use the term “sex” (and the terms “male”, “female” and “intersex”) to refer to biological differences in physical anatomy. I will use the term “gender identity” to refer to a person’s experience of self as a “boy,” “girl,” “man,” “woman,” or related social category. I will use the term “sex/gender” to refer to situations in which people the terms “sex” and “gender” in ways that are either unclear, undifferentiated or contested.

[2] Some might dispute this claim. One the one hand, some might suggest that gender identity – one’s personal sense of “who I am” as a gendered individual – is the proper criterion to use to identify a person’s gender. However, while a person’s gender identity appropriately captures a person’s social or psychological identity from a first-person point of view, it does not capture the person’s status as a biological being from a third-person point of view – that is, from the standpoint of a person observing the physical body. Conversely, a person who suggests that biological sex provides the criterion for identifying a person’s gender encounter’s the opposite problem, namely discounting the person’s first-person experience as a criterion for personal or social identity.

If you like what we are doing, please support us in any way that you can.