Michael F. Mascolo, Ph.D.

Our current form of democracy is not its most evolved form. It might be natural for people to feel that they are living in the most advanced of times – and that our assumed ways of doing things are the best that they can be. However, we should admit that although democracy has been effective for over 200 years, it is not perfect. We must work to make it better.

Western democracy has always relied on an adversarial system of political decision-making. Candidates and political parties debate over who has the best ideas and who should thus gain power. An adversarial democracy requires that competing parties share what might be called an “agonistic common ground”[i] – a set of shared beliefs that facilitates peaceful debate and collective decision-making. In recent decades, such beliefs have undergone decay. As a result, our adversarial system is pulling us apart more than it is bringing us together.

One alternative to an adversarial democracy is collaborative democracy. A collaborative democracy would be one that draws on principles and practice of conflict management to resolve social and political problems. It would focus on primarily on collaborative problem-solving between and among different factions or interests rather than competition for political power. A collaborative democracy would be one that acknowledges that different people have different needs, experiences and systems of belief. It would seek to resolve conflict among factions not by trying to beat the other, but by creating novel ways to meet our diverse needs at the same time. Instead of pitting my problem against yours, you and I join forces to solve each other’s problems without giving in on our core needs.

It was, of course, Winston Churchill who said, “Democracy is the worst form of Government except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time”. Although there is some controversy about what Churchill meant in this statement, what is important is the acknowledgement that even though we may feel that democracy is the best form of government, it has both weaknesses and challenges.

The strengths of democracy are obvious: democracy is a form of government that holds out the best chance that people can settle their differences peacefully. Democracy privileges the rights and dignity of individuals over the state. In a democracy, people are equal before the law. Democracy guarantees the freedoms to speak, assemble, think and pursue the good as one sees it – so long as one does not intrude upon the rights of others. Democracy is our best antidote against tyranny.

But democracy has weaknesses. Democracy is slow. It requires an educated public. It requires cooperation, good faith and both personal and collective effort. It requires some degree of agreement about shared public virtues that allow us to maintain democratic practices (e.g., faith in the democratic process; respect for the opinion of others; willingness to turn over power etc.). It is susceptible to the tyranny of the majority and to demagogues. And in the absence of an “agonistic common ground”, it can easily degenerate into “us versus them”.

Not so long ago, it was possible to think of political parties as having similar overarching goals while disagreeing upon the means to achieve those goals. Today, it seems that the extremes of different political parties disagree not only on the means, but also the ends. Different factions of the republic want different outcomes. As we move in different directions, we are pulling the nation apart.

Most democracies are adversarial systems. At least two candidates, parties or coalitions compete against each other to win elections and gain power. The process of campaigning involves courting voters by developing a program or set of ideas that can appeal to a majority of voters.

The most basic way that adversarial democracy works is through debate. At their best, debates serve an important purpose. In a debate, candidates compete against each other to see who has the best ideas for addressing the issues of the day. A debate is founded upon the idea of the “marketplace of ideas”. The competition between people is meant to function as a means of sharpening one’s ideas. Participants give each other the “gift” of their best ideas and arguments. By responding to the best that one’s debate partner has to offer, each participant creates the best ideas and arguments possible. Each participant submits his or her ideas to the populous. The person or party with the best ideas wins.

Cracks in the System

For it be constructive, the adversarial approach to democratic debate requires a set of shared beliefs and practices. Participants must agree to:

If these conditions are met, debates can be constructive. That is, they can function to improve the quality of the arguments and proposals made by each debater. In this way, there are circumstances in which debates can indeed improve the quality of proposals evaluated in the “marketplace of ideas”.

However, political discourse rarely honors all these principles. Democracy – like any ideal — is always unfulfilled. In recent decades, however, none of these principles is has been consistently honored in typical political debates. In recent decades, political debate has become more polarized[ii], uncivil[iii], aggressive[iv], and moralizing[v]. Debates are characterized by high levels of misinformation[vi], selective framing[vii], and moral denigration[viii] of the other.

One might suggest that there are two basic problems with our current adversarial approach to democratic decision making. First, current political parties appear to disagree not only about the means for solving collective problems, but more often about the very goals and values that ought to define the nation. In such a context, the stakes for any given decision about any given issue are high. In a national context in which factions are moving in different directions, conventional solutions to political discord – compromise – become less palatable.

Second, the goal of political decision making is not to meet the needs of the full range of constituents; the goal is to win. Even if debates, appropriately structured, can in principle produce a system in which the best ideas rise to the top, in practice, they produce zero-sum games in which one side’s win is the other side’s loss. In the context of increasingly polarized worldviews, winning and losing are increasingly experienced in moralizing and existential terms.

In such circumstances, parties often do what they feel they have to do to reach 51% of the vote. Under these conditions, winners rejoice and losers retrench. These are not circumstances for problem-solving; they are the conditions for disunion.

Among any group of people, viewpoints, opinions, and preferred solutions to problems tend to be in conflict. In adversarial democracy, conflict is solved through that seek to amass majority support for one side’s approach to solving problems over that of the other. In contrast, a collaborative democracy would build on the principles and practices of conflict resolution in order to address and resolve contentious social and political issues. Instead of viewing political conflict as a type of conflict, battle or competition, parties view the conflict as a problem-to-be-solved.

In a collaborative democracy, each party to a conflict is regarded not as a nameless or faceless enemy or opponent, but instead as a person or as a coalition of persons with human needs, interests, feelings and grievances. The problem-to-be-solved is not one winning a battle with one’s opponent, but instead of finding ways to meet the unmet needs and interests of the various parties to a conflict.

Collaborative democracy is based on an awareness of the dual motives involved in any human encounter. These include fear for the self (self-interest) and concern for the other. In any conflict, there is a need to acknowledge both of these motives. A conflict can be solved neither by capitulating one’s core needs to the other nor by posing one’s will on the other. In each of these solutions, l winners rejoice while losers suffer the pain of loss and shame. Suffering breeds resentment, and shame foments anger and rage.

Collaborative democracy is based on the idea that it is indeed possible – not always, but much more often than one might think – to resolve conflicts by identifying and simultaneously meeting the unmet needs each party to a conflict. The most basic way to approach shared decision-making involves the use of collaborative problem-solving.[1]

Collaborative Problem-Solving

In collaborative problem solving, the parties to any given conflict are seen as people who are trying to solve a problem. Each “side” has a particular problem that they are trying to solve. Usually, the problems that each “sides” are trying to solve are different ones. Collaborative problem-solving asks, “Instead of pitting one side against the other, how can we solve each side’s particular problems at the same time?”

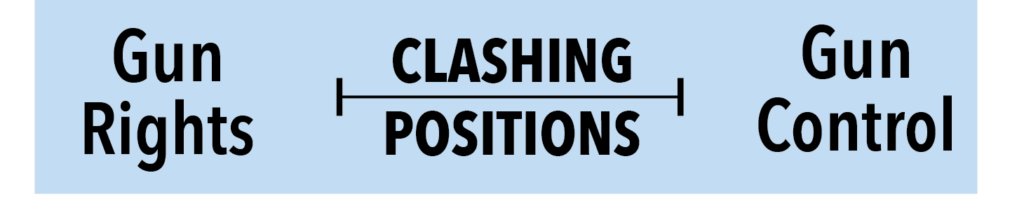

The reader may ask, “if the two sides are in conflict, how is it possible for both sides to get what they want?” The answer is that for many (and perhaps even most) conflicts, people tend to argue over the solutions to problems that have not yet been identified. For example, issues related to the highly contentious issue of gun violence are typically framed in terms of a battle between those who advocate gun control versus those who advocate gun rights. From this point of view, at the broadest level, the question becomes:

Should we permit or regulate gun ownership?

Framed in this way, we are asked to make a zero-sum choice: either we permit or restrict guns? The goal of permitting guns is in direct conflict with the goal of restricting them. It is not surprising that such a stark choice would quickly divide the room:

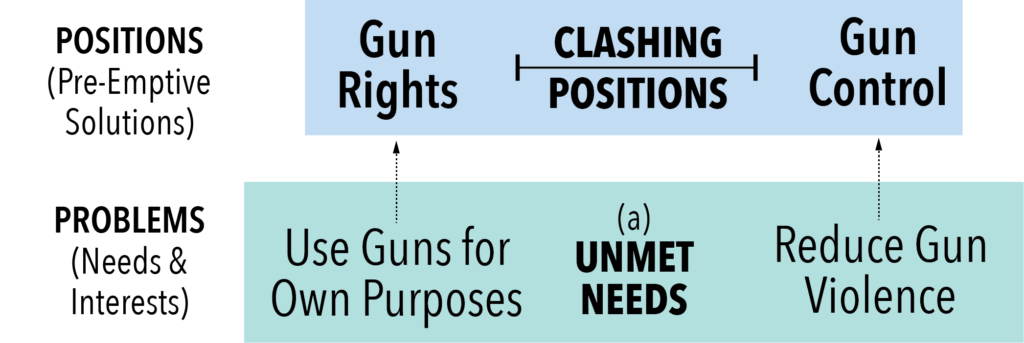

But this question is not framed as an attempt to solve a problem. Indeed, the genuine problem is never actually stated in the question. The problem at hand is not whether to permit or restrict guns. In fact, gun regulation is proposed as a solution to a problem – namely, the problems of how to reduce gun violence in society. Similarly, advocating the permitting of gun ownership is not a kind of problem. It too is a solution to a problem – namely the problem of ensuring that people are able to use guns for their chosen purposes.

When the issue is stated in this way, there is no alternative to thinking of the conflict as a type of battle. Each side tries to advance their position at the expense of the other. This is what typically occurs in political debates and campaigns. Political debates are not about solving problems; they are about advancing positions.

In collaborative problem-solving, the battle over positions is turned into a kind of problem-solving. That is, instead of battling over whether nor not to permit guns, the parties seek ways to solve the full range of problems that motivate the conflict in the first place:

When this happens, the process starts not with, should we permit or restrict guns, but instead something like:

How can we simultaneously reduce gun violence while also honoring the desire of people to own guns?

Collaborative problem-solving begins by articulating problems. The most important part of problem-solving is representing the problem itself. There are typically multiple diverse solutions for any given problem. If this is so, then once each party is assured that the “other side” is willing to acknowledge, respect and even try to help solve each other’s problems, fears begin to subside. Parties can then begin working together – without fear – in order to find novel ways to simultaneously solve each other’s problems. When this happens, novel solutions tend to emerge – often, with minimal effort.

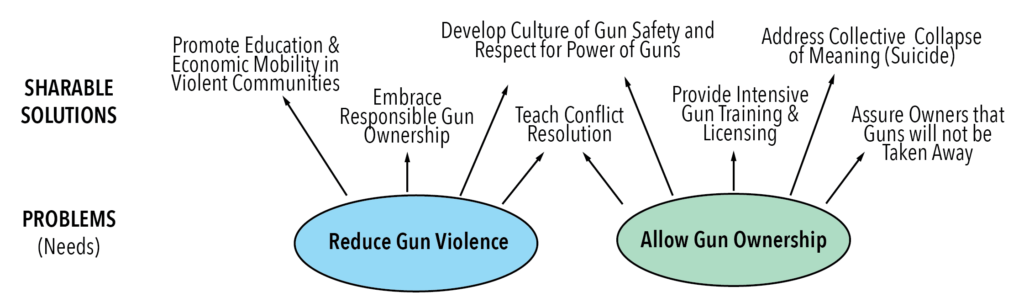

So, how can we reduce gun violence while simultaneously protecting gun ownership? If we are open to novel ways of thinking, we can see that there are many possible ways that these problems can be solved simultaneously. These are shown here:

In order to resolve political conflict, it is helpful to realize two important principles:

Because there are many ways to solve any given problem, it is often possible to develop novel solutions that appeal to multiple parties to a given issue. When we focus on underlying problems rather than pre-emptive solutions, fears begin to become attenuated. People find that they are able to work together en route to developing more agreement than they would typically think is possible.

In the case of gun violence, the moment we look beyond entrenched political positions, we can find that there are many ways to meet each side’s underlying needs and interests. Much gun violence occurs as a result of problems associated with lack of education, economic need, poverty and the poor means of resolving conflict. If this is so, then core origins of gun violence can be addressed by improving the infrastructure of communities, such as fostering educational attainment and economic mobility.

A national effort to teach effective conflict resolution help provide people with skills to solve social problems before then rise to the level of lethal conflict. Still further, most acts of gun violence occur because of suicide. Direct interventions to address the circumstances under which people choose to take their own lives (e.g., hopelessness, collapse of meaning, feeling left behind, depression) can help address the root causes of suicidality.

A major problem with the debate on gun violence is that gun owners – the vast majority of whom have deep respect for firearms – fear that political figures are motivated to take their guns away. Understanding the needs of gun owners can bring awareness to this issue. To the extent that their desire to use gun responsibly will not be thwarted, gun owners may be more likely to join forces with those who are concerned about gun violence to identify novel solutions to difficult problems. Given such assurances, it is likely that many gun owners would applaud the desire to promote a culture of responsible gun ownership, complete with rigorous training programs and even licensure for gun ownership.

People will rarely if ever attain full agreement on ways to solve collective problems. To be sure, in the solution described above, the full range of issues related to gun violence would not be resolved. However, collaborative solutions like that described above would nonetheless go a long way toward reducing the number gun deaths in society while simultaneously ensuring freedom of gun ownership. Collaborative solutions hold out the promise of meeting many of the needs of diverse parties to a conflict.

The us versus them approach to adversarial debate typically functions as a means to discredit the positions of people on either side. This is an unproductive form of social decision making.

It is possible to find collective solutions to divisive problems. What stops us is fear. We fear that if we consider the humanity of “the other side”, we will appear weak and “lose ground”. We fail to see that any genuine solution must not only meet our needs, but also those of “the other side”. So long as we treat “the other side” as a kind of enemy – as crazy, stupid, out of touch and even evil – we will continue to believe that the only way to resolve political conflict is to defeat the other side.

Collaborative democracy calls on people to work together – within local communities, municipalities as well as state and national governments – to develop novel solutions to the problem of meeting as many needs of parties to a conflict as possible. The process does not pit one set of social needs against the other. Instead, it mobilizes stakeholders to seek ways to meet each other’s needs under the presupposition that, more often than we might think, the needs of diverse parties to a conflict are not incompatible; they can often be met at the same time.

Skeptics may disagree. They might say: when there is a conflict, it is naïve to think that people can work together to resolved it. In a conflict, it is merely human nature for one party to want to win and the other to want to lose. It is not reasonable to believe that one can get both parties to collaborate and cooperate in this way. While these fears are understandable, they are nonetheless incorrect. Collaborative problem-solving works. It simply requires the skill and the will to use it.

It would be an error, of course, to think that politicians on the state and national levels can be easily moved to use collaborative practices in their decision-making. The structure of our current adversarial system all but ensures that this will not occur. Collaborative democracy is not likely to begin with the professional politicians. Instead, it will begin with the people.

Collaborative democracy can develop when individual people begin to collaborative problem-solving into their local spheres of influence. It will begin as people bring collaborative principles into their relationships, their families and workplaces. It will begin as local leaders use collaborative problem-solving to resolve social political disputes within communities and local municipalities. It will take off as leaders begin to see that collaborative problem-solving indeed works to bring people together to solve difficult problems. It will begin when we demand that our leaders explore alternatives to the forms of adversarial politics that are currently challenging our democratic system.

[1] Collaborative problem-solving is best suited for situations in which parties can separate basic problems from broader ideological concerns. However, in most political conflicts, the unmet needs of different parties are ideologically defined. While it is more difficult to resolve ideological conflict, it is nonetheless possible. Solving ideological conflicts requires more nuanced forms of conflict management. Such approaches exist and will be discussed further elsewhere.

[i] Stavrakakis, Y. (2018). Paradoxes of Polarization: Democracy’s Inherent Division and the (Anti-) Populist Challenge. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(1), 43 58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218756924

[ii] DellaPosta, D. (2020). Pluralistic Collapse: The “Oil Spill” Model of Mass Opinion Polarization. American Sociological Review, 85(3), 507–536. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1177/0003122420922989; Hill, S. J., & Tausanovitch, C. (2015). A disconnect in representation? Comparison of trends in congressional and public polarization. The Journal of Politics, 77(4), 1058–1075. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1086/682398; Neal, Z. P. (2020). A sign of the times? Weak and strong polarization in the US Congress, 1973–2016. Social Networks, 60, 103–112. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2018.07.007

[iii] Emerson, K., Joosse, A. P., Dukes, F., Willis, W., & Cowgill, K. H. (2015). Disrupting deliberative discourse: Strategic political incivility at the local level. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 32(3), 299–324. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1002/crq.21114; Hill, R. P., Capella, M., & Cho, Y.-N. (2015). Incivility in political advertisements: A look at the 2012 US presidential election. International Journal of Advertising: The Review of Marketing Communications, 34(5), 812–829. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1080/02650487.2015.1024386; Rowe, I. (2015). Civility 20: A comparative analysis of incivility in online political discussion. Information, Communication & Society, 18(2), 121–138. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.940365; Walter, A. S. (2021). Political incivility in the parliamentary, electoral and media arena: Crossing boundaries (A. S. Walter (Ed.)). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.4324/9781003029205

[iv] Robles, J.-M., Guevara, J.-A., Casas-Mas, B., & Gömez, D. (2022). When negativity is the fuel. Bots and political polarization in the COVID-19 debate. Comunicar (English Edition), 30(71), 59–71. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.3916/C71-2022-05; Torregrosa, J., D’Antonio-Maceiras, S., Villar-Rodríguez, G., Hussain, A., Cambria, E., & Camacho, D. (2022). A mixed approach for aggressive political discourse analysis on twitter. Cognitive Computation. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1007/s12559-022-10048-w

[v] Bayes, R. (2022). Moral convictions and threats to science. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 700(1), 86–96. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1177/00027162221083514; D’Amore, C., van Zomeren, M., & Koudenburg, N. (2022). Attitude moralization within polarized contexts: An emotional value-protective response to dyadic harm cues. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 48(11), 1566–1579. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1177/01461672211047375; Phelan, S. (2022). Friends, enemies, and agonists: Politics, morality and media in the COVID-19 conjuncture. Discourse & Society, 33(6), 744–757. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1177/09579265221095408; Tappin, B. M., & McKay, R. T. (2019). Moral polarization and out-party hostility in the US political context. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 7(1), 213–245. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.5964/jspp.v7i1.1090

[vi] DellaPosta, D. (2020). Pluralistic Collapse: The “Oil Spill” Model of Mass Opinion Polarization. American Sociological Review, 85(3), 507–536. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1177/0003122420922989; Hill, S. J., & Tausanovitch, C. (2015). A disconnect in representation? Comparison of trends in congressional and public polarization. The Journal of Politics, 77(4), 1058–1075. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1086/682398; Neal, Z. P. (2020). A sign of the times? Weak and strong polarization in the US Congress, 1973–2016. Social Networks, 60, 103–112. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2018.07.007

[vii] Cho, J., Shah, D. V., Nah, S., & Brossard, D. (2009). “Split screens” and “spin rooms”: Debate modality, post-debate coverage, and the new videomalaise. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 53(2), 242–261. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1080/08838150902907827; Clifford, S. (2019). How emotional frames moralize and polarize political attitudes. Political Psychology, 40(1), 75–91. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1111/pops.12507; Maurer, M., & Reinemann, C. (2006). Learning Versus Knowing: Effects of Misinformation in Televised Debates. Communication Research, 33(6), 489–506. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1177/0093650206293252

[viii] Abramowitz, A., & McCoy, J. (2019). United States: Racial resentment, negative partisanship, and polarization in Trump’s America. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 681(1), 137–156. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1177/0002716218811309; Schraufnagel, S., Casas, N., Bacharz, T., Holm, N., & Miller, C. (2021). Legislative conflict: Are ideologues more uncivil? In A. S. Walter (Ed.), Political incivility in the parliamentary, electoral and media arena: Crossing boundaries. (pp. 69–86). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.; Schweitzer, E. (2009). Convergence in E-Campaigning: Comparing the Use of Attacks on German and American Political Web Sites. Conference Papers — American Sociological Association, 1.

If you like what we are doing, please support us in any way that you can.