This is the third article of a series on “The New Epigenetics”. The epigenetic perspective in biology and psychology provides a solution to the clunky, age-old nature-nurture issue. It says that the old view that pits nature against nurture (genes against environment) as rival explanations for how development happens is flawed. Genes and environments are partners in development; they can’t work without each other. This has radical implications for how we understand biology, development, and human nature. Because different political ideologies are build largely around different conceptions of human nature, it has deep implications for political life as well.

Recently, I was asked the following:

“Do you agree that some children are born ‘crime prone’ or criminal, while others are not so?”

Let’s start with the easy question: “Are some children born…criminal?” Well, of course not. Newborn babies do not engage in criminal activity. So they can’t be born criminal. Further, “criminal” is a cultural category. There are no “criminals” before there are cultures, laws, and normative practices. Criminal activity must necessarily develop over time; it is not a part of one’s constitution.

How about the other part of the question: Are children born “crime prone”? Again, there is something somewhat wrong with this question. A child may be born with biological dispositions that may, under certain circumstances, increase the likelihood that he or she will develop into a person who commits crimes. While some biological conditions may make it more likely that a child will develop into rule violating behavior, criminal behavior is something that develops. It is neither preformed nor predetermined.

Neither Genes nor Environment Alone: The Epigenetic View

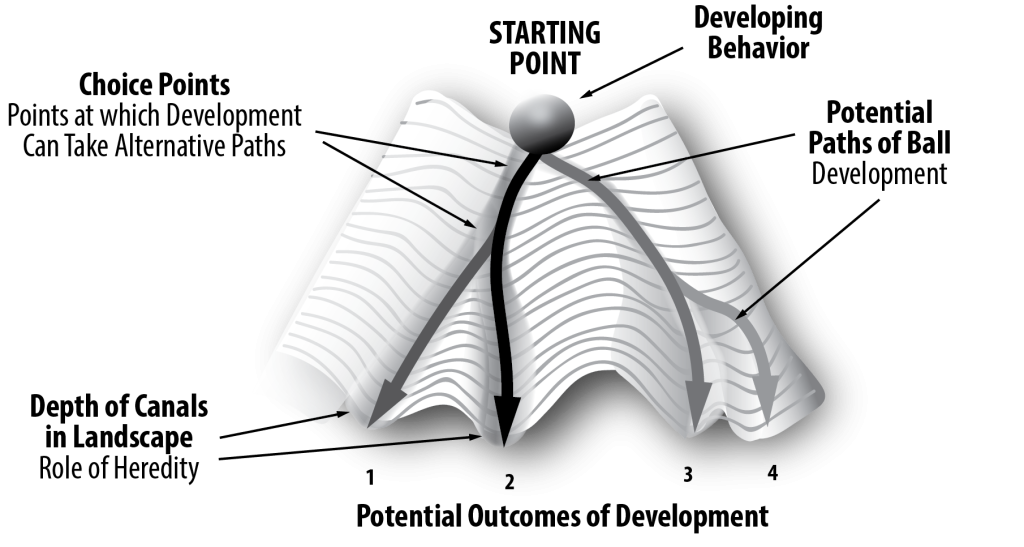

To understand how biological dispositions can make developmental outcomes (for example, criminal behavior) more or less likely, consider Figure 1. This figure shows the famous “epigenetic landscape”.[i] This is a model of how “nature” interacts with “nurture” over time to produce different outcomes. In the model, development is represented by a ball that likes on the top of a landscape. The landscape represents the effects of heredity. The landscape contains a series of canals. As parts of the landscape, the canals are determined by heredity. They show the various possible pathways that development can take over time.

Figure 1. The Epigenetic Landscape

We immediately see that heredity does not specify the path that development will take. Instead, it sets up possible pathways that development can take. Genes are not fixed blueprints. They do not determine developmental outcomes. Developmental outcomes are always the product of genes interacting with environments.

In the landscape model, the process of development occurs as the ball rolls down the hill. As it rolls, the ball reaches a series of choice points. At these points, development in any individual can take many different pathways. As can be seen in Figure 1, some canals on the landscape are deeper than others. The depths of the canals, again, are determined by heredity.

At each choice point, the ball is most likely to take the deepest pathway – the pathway made most possible by heredity. However, what is happening in the environment of the developing ball can move the ball of development from one pathway to another. While development is most likely to take the deepest path, the actual path the ball tasks is determined by the ways in which the environment interacts with the landscape. Even though development is most likely to take the deepest paths – those made more possible by heredity – environment can move development from deep paths to alternative pathways.

And so, there is no fixed plan for development. Genes and environments work together in development. Genes cannot operate without environment; environment cannot operate without genes. In fact, genes and environments (including the biological environment) influence each other.

Replacing Old and Tired Thinking: The Development of Criminal Behavior is Epigenetic

This is the case in the development of all forms of human action, including the development of criminal behavior. It is indeed fair to say that some children come into the world with dispositions that, under certain circumstances, increase the likelihood that they will develop proclivities toward criminal behavior[ii]. In different people, genes play a role in biasing development toward attentional difficulties, difficulties in regulating emotion and action, callous emotional temperament, learning disabilities, heightened levels of aggression or depression, increased receptivity to the negative effects of drugs and alcohol, and many other conditions. Note – the pathway from genes toward or away from criminal behavior is always indirect and always requires interaction with the environment. Here are some examples.

Genes increase the likelihood that an individual may have one of many different types of attentional difficulties (what is commonly called attention deficit disorder), difficulties with executive functioning and self-regulation (i.e., regulating thinking, feeling and action), and learning disabilities)[iii]. Children who experience such difficulties are more likely to experience difficulties in school and to have poor academic achievement[iv]. Difficulties in school make it more difficult for children to prepare successfully for careers and other normative activities. This increases the likelihood that children will engage in norm-breaking and rule violating behavior. Children and adolescents who engage in such forms of action are more likely to be rejected by peers[v]. This increases the likelihood that such individuals will engage in various forms of criminal behavior.

Genes increase the likelihood that some children will develop callous or aggressive emotional dispositions[vi]. A child with a callous emotional disposition finds it difficult to empathize and appreciate the feelings of others. They are more likely to act impulsively without regard for the feelings of others. Children with irritable and aggressive dispositions are more likely react aggressively in situations involving peer conflict, or to proactively use aggression to get their way with others[vii]. Such children are more likely to be rejected by peers, punished by adults. In this way, the genetically influenced dispositions of children (their “nature”) influences how others interact with them (their “nurture”). Negative interactions with others tend to create a cascade of negative interactions over time. As they escalate, children move toward increasingly anti-social and even criminal activity.

In some people, genes increase the likelihood of responding negatively to the effects of drugs and alcohol[viii]. When they experiment with drugs and alcohol, such individuals are more likely to become physically and psychologically dependent on these substances. Dependency brings about physical changes in the brain and body[ix]. Such changes are likely involved in producing the cravings that make it difficult for people to abstain from alcohol and drugs (the phenomenon that people typically refer to as “addiction”). Left unchecked, drug and alcohol abuse tend to bring about a vicious cycle – abuse begets more abuse. Illicit drug use itself is often treated as a criminal outcome; alcohol and drug use are processes that dispose individuals toward a wide variety of criminal activities[x].

Genes Matter — But They Are Only Part of the Developing System

There are two major points to make about the relation between genes and criminal behavior. First, the type of genetically influenced behavioral dispositions under discussion — attentional problems, difficulties with executive control, learning disabilities, callous and aggressive temperament, differential reactions to alcohol and drugs, and so forth – are not themselves forms of criminal activity. They are forms of behavior that arise from interactions between genes and environments that increase the likelihood that a person will develop in the direction or criminal activity.

Second, genes do not operate independent of their biological, physical, and social environments. The more biological risks that a child has, the more likely he or she is to develop patterns of criminal behavior. However, children who do not have the types of genetically influenced dispositions discussed above can develop into adults who commit crime; children who have such dispositions can develop into successful well-functioning adults. As shown in Figure 1, it is the interaction between a person’s biological dispositions and the effects of the environment at different points in time that produces any given developmental outcome[xi]. Given sustained patterns of systemic intervention[xii] and social support [xiii]over time – firm and responsive parenting, modified educational experiences; social skills training; the availability of accessible and well-respected employment; appropriate values and a sense of hope — children who might otherwise be at risk to develop patterns of criminal behavior can and do develop into successful and well-adjusted adults[xiv].

There are No “Criminal Brains”

This shows why the old nature-nurture argument is so flawed. It is based on a false premise – namely the premise that nature and nurture are independent of each other – that there can be an effect of one that is independent of the other. It is important to reiterate that genes and environments affect each other in the development of all behavior. Genes affect the development of dispositions which increase the likelihood of some behaviors over others. Such behaviors then influence the environment. Changes in the environment then feed back and cause changes in a person’s biology – including the “turning on” and “turning off” of genes. Here is how the authors of one study assessing the ways in which genes and environment interact in the development of depression put it: “The findings provide support for an integrated model in which changes in DNA methylation [a biological process that modifies genetic expression], resulting from neighborhood crime, can result in an increase or decrease in gene activity which, in turn, influences depressive symptoms”[xv].

Genes are involved in all behaviors. All forms of thinking, feeling, and acting occur as processes “above” the level of the genes function to “turn on” and “turn off” gene activity as part of the very process that we call action. If this is so, it simply doesn’t make sense to try to divide up behavior into separate genetic and environmental causes. What’s true of behavior in the moment is true of behavior as it develops over time. There are relation between genes and the development of criminal activity. But the relations are indirect, complex, circuitous, and malleable. There is no such thing as a “bad brain”[xvi] or “criminal brain”[xvii]. Criminal activity, like any other form of human behavior, develops as a constrained but open process.

References=

[i] Waddington CH. (1957). The Strategy of the Genes. London, UK: Volume George Allen and Unwin.

[ii] Graham, A., Barnes, J. C., Liu, H., & Cullen, F. T. (2022). Beyond a Crime Gene: Genetic Literacy and Correctional Orientation. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 47(3), 485–505. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09595-5

[iii] Boisvert, D., Wright, J., Knopik, V., & Vaske, J. (2012). Genetic and Environmental Overlap between Low Self-Control and Delinquency. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 28(3), 477–507. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1007/s10940-011-9150-x

[iv] Newsome, J., Boisvert, D., & Wright, J. P. (2014). Genetic and environmental influences on the co-occurrence of early academic achievement and externalizing behavior. Journal of Criminal Justice, 42(1), 45–53. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2013.12.002

[v] TenEyck, M., & Barnes, J. C. (2015). Examining the impact of peer group selection on self-reported delinquency: A consideration of active gene–environment correlation. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 42(7), 741–762. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1177/0093854814563068

[vi] Beaver, K. M., Barnes, J. C., May, J. S., & Schwartz, J. A. (2011). Psychopathic personality traits, genetic risk, and gene-environment correlations. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38(9), 896–912. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1177/0093854811411153; Cecil, C. A. M., Lysenko, L. J., Jaffee, S. R., Pingault, J.-B., Smith, R. G., Relton, C. L., Woodward, G., McArdle, W., Mill, J., & Barker, E. D. (2014). Environmental risk, Oxytocin Receptor Gene (OXTR) methylation and youth callous-unemotional traits: a 13-year longitudinal study. Molecular Psychiatry, 19(10), 1071–1077. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1038/mp.2014.95

[vii] Tremblay, R. E. (2015). Developmental origins of chronic physical aggression: An international perspective on using singletons, twins and epigenetics. European Journal of Criminology, 12(5), 551–561. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1177/1477370815600617

[viii] Thapar, A. (2015). Parents and genes and their effects on alcohol, drugs, and crime in triparental families. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(6), 508–809. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15020263

[ix] Eagle, A., Al Masraf, B., & Robison, A. J. (2019). Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of reward circuitry in drug addiction. In M. Torregrossa (Ed.), Neural mechanisms of addiction. (pp. 23–34). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-812202-0.00003-8

[x] Terranova, C., Tucci, M., Sartore, D., Cavarzeran, F., Barzon, L., Palù, G., & Ferrara, S. D. (2012). Alcohol dependence and criminal behavior: Preliminary results of an association study of environmental and genetic factors in an Italian male population. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 57(5), 1343–1348. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2012.02243.x; Tolou-Shams, M., FolK, J. B., Holloway, E. D., Ordorica, C. M., Dauria, E. F., Kemp, K., & Marshall, B. D. L. (2023). Psychiatric and substance-related problems predict recidivism for first-time justice-involved youth. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 51(1), 35–46.

[xi] Leshem, R., & Weisburd, D. (2019). Epigenetics and hot spots of crime: Rethinking the relationship between genetics and criminal behavior. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 35(2), 186–204. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1177/1043986219828924

[xii] Johnson, M. E., & Waller, R. J. (2006). A review of effective interventions for youth with aggressive behaviors who meet diagnostic criteria for conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 17(2), 67–80. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1300/J085v17n02_05’ Linseisen, T. (2013). Effective interventions for youth with oppositional defiant disorder. In C. Franklin, M. B. Harris, & P. Allen-Meares (Eds.), The school services sourcebook: A guide for school-based professionals., 2nd ed. (pp. 91–103). Oxford University Press; Smallbone, S., Rayment, M. S., Crissman, B., & Shumack, D. (2008). Treatment with youth who have committed sexual offences: Extending the reach of systemic interventions through collaborative partnerships. Clinical Psychologist, 12(3), 109–116. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1080/13284200802520839; Zagar, R. J., Grove, W. M., & Busch, K. G. (2013). Delinquency best treatments: How to divert youths from violence while saving lives and detention costs. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 31(3), 381–396. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1002/bsl.2062

[xiii] Barnes, J. C., & Beaver, K. M. (2012). Marriage and Desistance From Crime: A Consideration of Gene-Environment Correlation. Journal of Marriage & Family, 74(1), 19–33. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00884.x; Watts, S. J. (2018). When does religion matter with regard to crime? Examining the relationship between genetics, religiosity, and criminal behavior. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 45(8), 1192–1212. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1177/0093854818777556

[xiv] Beaver, K. M., Schwartz, J. A., Connolly, E. J., Said Al-Ghamdi, M., & Nezar Kobeisy, A. (2015). The Role of Parenting in the Prediction of Criminal Involvement: Findings From a Nationally Representative Sample of Youth and a Sample of Adopted Youth. Developmental Psychology, 51(3), 301–308. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1037/a0038672

[xv] Lei, M.-K., Beach, S. R. H., Simons, R. L., & Philibert, R. A. (2015). Neighborhood crime and depressive symptoms among African American women: Genetic moderation and epigenetic mediation of effects. Social Science & Medicine, 146, 120–128. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.035

[xvi] Jorgensen, C., Anderson, N., & Barnes, J. (2016). Bad Brains: Crime and Drug Abuse from a Neurocriminological Perspective. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 41(1), 47–69. https://doi-org.proxy3.noblenet.org/10.1007/s12103-015-9328-0

[xvii] Rafter, N., Posick, C., & Rocque, M. (2016). The criminal brain: Understanding biological theories of crime, 2nd ed. New York University Press.

If you like what we are doing, please support us in any way that you can.